Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

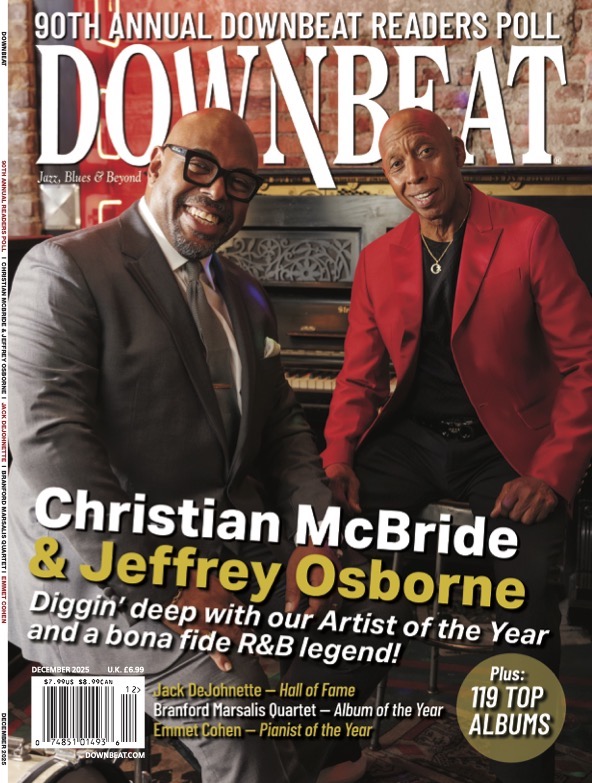

In Memoriam: Jack DeJohnette, 1942–2025

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

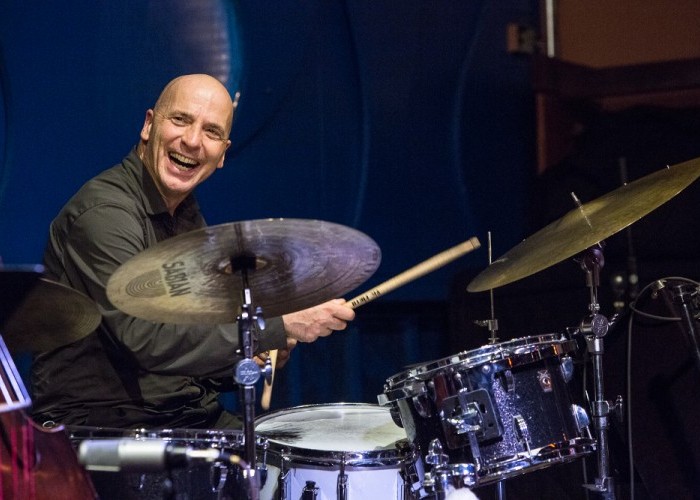

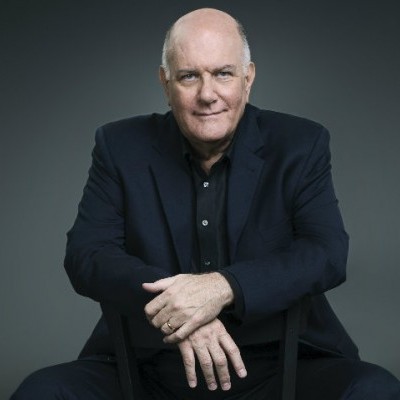

Some of drummer Joey Baron’s most recent recordings have been duo collaborations—Now You Hear Me, a meticulously crafted studio project with percussionist Robyn Schulkowsky, and Live!, a document of spontaneous composition at Zurich’s Unerhört Festival with pioneering Swiss free-jazz pianist Irène Schweizer.

(Photo: Mark Sheldon)I recall seeing you and Robyn performing during a two-week residency at Grand Central Station’s Vanderbilt Hall in 2005.

Yes, we played these instruments that Robyn constructed, these very large sub-bass marimba bars that sit on top of resonators. She had worked with a sculptor who helped her build these things; I had no idea what they were doing at the time. So, we developed a technique on how to play these instruments that were basically Robyn’s creation. Harry Partch [1901–’74] did a few things with instruments he invented, but he stopped at a certain point and didn’t go any further. Robyn kind of picked it up from that point and came to her own conclusions of how to solve the problems of getting instruments that you create acoustically to play those really deep tones. So, we developed this language, this technique of playing them. And we did a whole CD on them called Dinosaur Dances. We put all these instruments into a truck and drove from Berlin onto a ferry, got off in Norway and went up to Rainbow Studio in Oslo and had Jan Erik Kongshaug engineer the session.

Now You Hear Me was recorded in the Berlin practice room you share with Robyn.

It’s a wonderful room and it sounds great, especially when you play quiet. It was fun to do a quiet drum duo, because a lot of times those instruments speak the best when they’re played on a softer dynamic scale. And our engineer, Adrian von Ripka, who is a real tonemeister, was able to capture what the room gave us. We didn’t have any baffling, there were no headphones being used. What you heard was the way it was.

The opening piece, “Castings,” segues from you and Robyn playing wooden dowels with your hands to you on the kit doing a shuffle-swing beat with a steady ride cymbal pulse. Was that an intuitive detour or was it part of an arrangement?

It was actually a separate piece. We had ideas to do all these different pieces, and rather than record straight through, we would stop and readjust the mics completely, just to get the optimum sound for each different situation. We recorded the dowels, the drum set segment, Robyn on her standup set playing tympani and drums and metal all separately, so that the integrity of the sound was kept. Once we had all these pieces, we had to decide which worked best together.

We wanted to make a record where the whole thing tells a story. And it’s a story that is determined by what you, the listener, perceive through the act of listening. For me, it’s a different story every time I hear it. And I don’t have to worry about what to call it. Could be jazz, could be new music. It’s composed, but there’s improvisation going on and there’s a lot of heart and emotion. It’s whatever anybody wants to call it.

Listening intently seems to be the key to this duo.

Yes, that’s really at the core of it. And maybe listening outside of your comfort zone: instead of going on automatic, really hearing sounds and letting that dictate what comes next in the music. That’s something that I’ve learned from Robyn, who is acutely aware of sounds. She’s mostly been a soloist or an ensemble player in chamber music, where sound is really, really important. And to have a dialogue with people who are on that level, who listen that closely, is really enjoyable.

It’s such an amazing moment when you sit down and turn off all the distractions—email, phone, TV or just closing a window—and totally listen to something. That “Aha!” moment when something comes out that you didn’t hear before is a revelation. That’s been a real inspiring push for me lately. That touches me in the same way as when I first heard Carmen McRae sing and thought, “Wow! I want to be a part of the team that gets that happening.” Now, when I play music I want to be able to generate that kind of invitation to other people—the way it was extended to me.

Now You Hear Me stands as your manifesto for playing drums and percussion without needing chordal instruments.

Well, it’s not so much what we don’t need but that this deserves a shot, too. I spent my whole life learning how to accompany chordal instruments. And I love playing with people who play great chords, especially in that tradition of standard songs, where harmony is really juicy and somebody who really knows what they’re doing can make such great music out of what could be normal Real Book chord changes. Being a part of that is just as thrilling to me, and I don’t want to say I don’t want to do that.

I’m just saying, “Wouldn’t it be great if there was also room for this other thing to happen?” Not instead of, but that it could be on the same tier as an option for people who want to hear music, where it’s on an equal setting, rather than being just a novelty.

When did you have this epiphany about making music on the drums?

I think it goes back to when I was at the Berklee College of Music. I remember John LaPorta—I was so intimidated by him—announced one day, “OK, from now on, all you drummers are going to buy a melodica.” The idea being that drums aren’t a musical instrument. I will never forget that instant. It’s like it was yesterday. My mind snapped and I just felt like, “Oh, yeah?” At that point, I decided to model something otherwise, not to prove him wrong, but I just took that as a challenge to make music on the drums.

I mean, it’s 2018 and people still have that reaction toward drummers. Whether they admit it or not, musicians have that reaction, colleagues have that reaction. It’s just so incorrect. But I feel so fortunate to know people who don’t have that perception, and I’m able to work with them to develop a new language on the drums. I feel so hopeful that the perception of these instruments will somehow change. And I’d like to be part of that process. DB

Jack DeJohnette boasted a musical resume that was as long as it was fearsome.

Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

D’Angelo achieved commercial and critical success experimenting with a fusion of jazz, funk, soul, R&B and hip-hop.

Oct 14, 2025 1:47 PM

D’Angelo, a Grammy-winning R&B and neo-soul singer, guitarist and pianist who exerted a profound influence on 21st…

To see the complete list of nominations for the 2026 Grammy Awards, go to grammy.com.

Nov 11, 2025 12:35 PM

The nominations for the 2026 Grammy Awards are in, with plenty to smile about for the worlds of jazz, blues and beyond.…

Drummond was cherished by generations of mainstream jazz listeners and bandleaders for his authoritative tonal presence, a defining quality of his style most apparent when he played his instrument unamplified.

Nov 4, 2025 11:39 AM

Ray Drummond, a first-call bassist who appeared on hundreds of albums as a sideman for some of the top names in jazz…

Jim McNeely’s singular body of work had a profound and lasting influence on many of today’s top jazz composers in the U.S. and in Europe.

Oct 7, 2025 3:40 PM

Pianist Jim McNeely, one of the most distinguished large ensemble jazz composers of his generation, died Sept. 26 at…