Aug 26, 2025 1:53 PM

Blindfold Test: Buster Williams

Buster Williams, who at the age of 83 has been on the scene for 65 years, had never done a Blindfold Test. The first…

Some of drummer Joey Baron’s most recent recordings have been duo collaborations—Now You Hear Me, a meticulously crafted studio project with percussionist Robyn Schulkowsky, and Live!, a document of spontaneous composition at Zurich’s Unerhört Festival with pioneering Swiss free-jazz pianist Irène Schweizer.

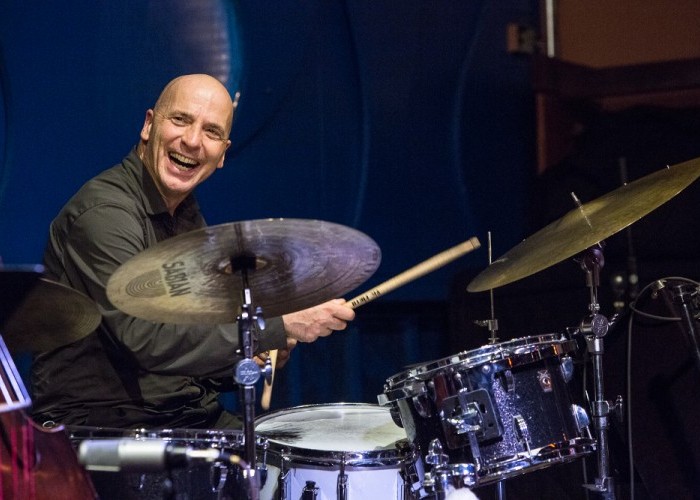

(Photo: Mark Sheldon)Over the course of his career, drummer Joey Baron has shown a knack for bringing just the right touch to any setting: from swinging with Carmen McRae to skronking with John Zorn or supplying simpatico grooves on eight Bill Frisell albums and the last four John Abercrombie Quartet recordings.

“Joey is a master musician, a peerless technician and a joyful collaborator,” Zorn said. “His focus is always 100 percent on the music. He hears everything and his reaction time is lighting fast. He is always finding new areas to explore and new heights to climb, and he loves surprising himself, his bandmates and the audience.”

Baron’s musical vocabulary is as vast as his fertile imagination. Dealing with sticks, brushes, mallets, fingertips or whatever else might be at hand, he has an uncanny ability to generate a diverse array of sounds from a snare drum, a cymbal or a hi-hat.

He can shift from a gentle snare brushstroke to a violent cymbal crash with the deftness and swiftness of a martial arts master. He might swing on the ride symbol in the old-school tradition of his Los Angeles mentor Donald Bailey one moment, then ring harmonics out of a cymbal in zen-like fashion the next.

But it is in duo settings that all of his keen instincts and finely honed skills come to the fore.

Two recent releases for the Intakt label—Now You Hear Me, a meticulously crafted studio project with percussionist Robyn Schulkowsky, and Live!, a document of spontaneous composition at Zurich’s Unerhört Festival with pioneering Swiss free-jazz pianist Irène Schweizer—find the highly empathetic drummer in vastly different settings. The 77-year-old Schweitzer, who has recorded piano-drums duets with Andrew Cyrille, Hamid Drake and Han Bennink, said, “As an improviser, I have appreciated Joey’s drumming very much, no matter with whom he was playing, because he is a great listener and excellent player. Our concert was completely improvised music. I listen to this CD now and I still like what we played then, and I do hope that there will be a second time whenever Joey is ready.”

Schulkowsky—who played a sprawling assortment of drums, various metal percussion and some instruments of her own design in her duet with Baron—noted, “Joey is a musician who, in the process of music-making, is willing to take risks while at the same time inviting others to contribute in a similar fashion. The big picture for him is always the music, and he acts compositionally in every situation.”

In a recent phone interview, Baron, who was in Berlin for some duets with Schulkowsky, addressed his aesthetic choices, the inspiration behind his desire to push the envelope on the kit and the all-important need to listen intently. Below are edited excerpts.

Let’s talk about your early gig with Carmen McRae.

To me, that was a dream gig. I wish I could do it again knowing what I know now, because I didn’t feel like I was really qualified to do it when I did. But she obviously saw something that allowed her to say, “OK, you got the gig.” I learned so much from her: the way that she walked out on the stage or the way she never wasted a note. She didn’t have the greatest voice of all the vocalists, but, man, for my ears she did more with what she had than all of the others.

Did you record with her?

We did a record called Live At The Great American Music Hall for Blue Note in 1976 when George Butler was in charge of the label. There was a recording we did, Blue Note Live At The Roxy [various artists], where I ended up playing Alphonse Mouzon’s drums; I had to stand up to hit the ride cymbal. It was a Blue Note showcase where we played a set, Ronnie Laws played and Bobby Lyle played, and they made a double vinyl record out of it with a few tracks from everybody. Most of my time with Carmen was mainly just live performances. I left her after about three years and began working with Al Jarreau.

Playing with McRae and Jarreau seems quite different than your recent duo recordings with Robyn and Irène. How did you make the transition from playing the backbeat to this other place, where you’re reinventing the language on the kit?

It’s not really a conscious decision. It was something that was always a part of my interest, going back to when I started playing the drums at age 9. As a kid growing up in Richmond, Virginia, my parents would take me to the park on a Sunday and I would set up my drums and just play solo for a few hours. Even when I was playing with Carmen and doing, for lack of a better word, super-straightahead gigs in Los Angeles, I was also doing solo concerts and playing pieces that weren’t about soloing over ostinatos and doing metric tricks and stuff like that.

How did you begin collaborating with Robyn, whose work has elements in common with composers like Stockhausen and Xenakis?

She hired me in 2000 to be part of a very large piece that she was putting on outdoors in Potsdam, Germany, that involved 80 roller skaters and six percussionists, three classical people, Robyn, me on drum set and then Fredy Studer, who was a good friend and my link to this project. I didn’t realize it, but I was in over my head at the time; I didn’t have a clue.

When I walked into rehearsal at Robyn’s loft, I had such a typical New York attitude like, “OK, let’s just play this shit, so I can get back to my room. Gimme the chart.” I laugh about it now; I didn’t get it at all. But slowly, it dawned on me and I got really interested in and seduced by the music and the way it was constructed. I hadn’t experienced anything like that before. Shortly after that performance we got involved personally and musically. We’d practice together, we’d work on things together. And I hadn’t had the opportunity to do that in such an open way before. In a lot of ways, drummers are guarded about their things or really tunnel-visioned in what they work on—isolated studies of funk chops, swing chops, paradiddles, coordination. But with Robyn, there’s a lot of sharing of information that goes on, and it’s all about playing music together.

“What I got from Percy was the dignity of playing the bass,” Buster Williams said of Percy Heath.

Aug 26, 2025 1:53 PM

Buster Williams, who at the age of 83 has been on the scene for 65 years, had never done a Blindfold Test. The first…

Don and Maureen Sickler serve as the keepers of engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s flame at Van Gelder Studio, perhaps the most famous recording studio in jazz history.

Sep 3, 2025 12:02 PM

On the last Sunday of 2024, in the control room of Van Gelder Studio, Don and Maureen Sickler, co-owners since Rudy Van…

The Free Slave, Cosmos Nucleus and Sunset To Dawn: three classic Muse albums being reissued this fall by Timer Traveler Recordings.

Aug 26, 2025 1:32 PM

Record producer and “Jazz Detective” Zev Feldman has launched his next endeavor, the archival label Time Traveler…

This year’s Jazz em Agosto set by the Darius Jones Trio captured the titular alto saxophonist at his most ferocious.

Aug 26, 2025 1:31 PM

The organizers of Lisbon, Portugal’s Jazz em Agosto Festival assume its audience is thoughtful and independent. Over…

Trio aRT with its avalanche of instrumentation: from left, Pheeroan akLaff, Scott Robinson and Julian Thayer.

Sep 3, 2025 12:03 PM

Trio aRT, a working unit since 1988, shockingly released its very first studio recording this summer. Recorded in…