Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

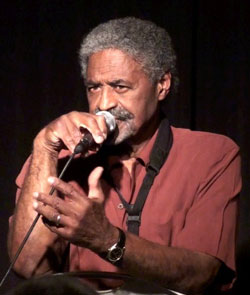

Charles McPherson

(Photo: )Was it personal for you to be involved in a film about Charlie Parker, especially given the fact you’re both originally from Missouri?

That part of the country—Kansas City and Joplin—is right in the middle of the U.S. It’s an interesting area because it’s almost a combination of East/West/North/South. It’s kind of its own little thing and the people have their own little personas. This area right in the heart is an interesting mixture, I think, of genetics and just cultural soup. Genetically, you have the interplay between African-Americans, Caucasians and Indians because a lot of that’s Indian territory. I think the mixture of all of those things, including the regional influences [from cities] like New Orleans, produces kind of an interesting group of folks on more than one level. And when it comes to making the music, which sounds self-serving since I’m from there, you’re also getting some influences from everywhere. When Charlie Parker came up, it was during Prohibition; a lot of the U.S. had no alcohol. But the area of Kansas City, that one town was nothing but alcohol. So you got all of these people who were drinking and it’s legal, and all of these clubs. It’s producing all these venues in which to play and attracting musicians from all over the country. They all congregate in Kansas City because it’s a wide-open town and there’s a lot of work.

That whole swing era was happening in that town, and Charlie Parker is a product of that, along with a lot of other great musicians like Count Basie. When I came along, it wasn’t Kansas City. Joplin is south of that and much later, it was 20 years later. But still, there’s a little remnant of it. My mom and dad are people like Charlie Parker, they are from that generation. So I heard that kind of music and how people played it and their particular idiosyncratic way of dealing with music. I heard that when I was a kid. And Kansas City, that part of the country the people are into the blues—and so am I. I consider myself a blues player. I mean, I play jazz and all of that, but the blues is very important to me. It’s not always that important to all jazz musicians. They think of the blues as something over here on the side, but to me, it’s a very important part of the equation of what jazz is. For me, I do have some precepts of what I think it is and the blues is definitely one of them. In my performance, whenever I play, I always make a point of playing the blues a couple times a night. That’s the way I do it and it’s deliberate.

What lies ahead for Charles McPherson—any upcoming projects and tours?

I’m working on a new project and hope to have it ready maybe early next year. I haven’t recorded, and I don’t like saying it, in a few years. The recording industry has just changed a lot. But I am writing more now. I go back and forth to New York a lot and I’ve been involved with Lincoln Center, with Wynton Marsalis’ mini-projects, Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola, Jazz Standard, Village Vanguard—just all of the New York clubs. I’ll be heading out to England and Spain in November, but in the U.S., I’ll be in Chicago in early August, Wisconsin and some things here in San Diego.

Will jazz always have a future?

I hear young saxophone players who are talented and interesting. Jazz music will always be a part of the global musical fabric. I don’t know if it’ll ever be pop; it might always be considered a little esoteric or alternative. But in every generation, there’s always going to be a few who are going to be enamored of it, enough so to play it and enough so to actually be a jazz fan, even if they don’t play. And it’s part of the academic situation now. Jazz is being taught in high schools and colleges, where they have a jazz division or a jazz department. Also, there are many jazz musicians who are adjunct [professors]. If it weren’t for the academic situation, we’d have a harder time. It’s another way to generate a livelihood for jazz musicians. So there’s always going to be a future for jazz. But I don’t think it will ever be like Lady Gaga [laughs]. Let’s put it that way.

—Shannon J. Effinger

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…