Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

In Memoriam: Al Foster, 1943–2025

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

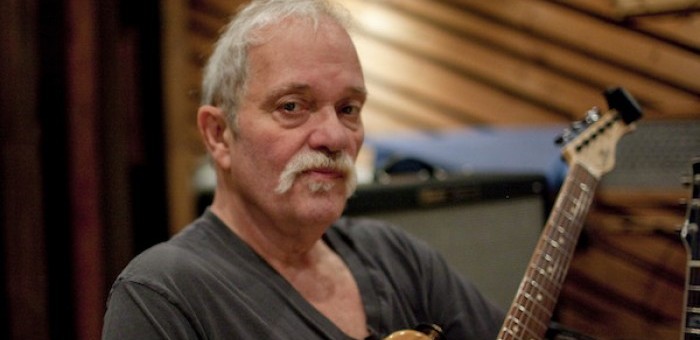

John Abercrombie (1944–2017)

(Photo: John Rogers/ECM Records)As a tribute to guitarist John Abercrombie, who died Aug. 22, DownBeat has posted the following feature, “The Moment Looks for You,” written by Dan Ouellette and published in our October 2012 issue.

There were no straight lines, no sudden leaps, no predictable trajectory in John Abercrombie’s coming of age as a jazz guitarist. He didn’t arrive as a child prodigy nor did he exude an overpowering confidence. He came up listening to Chuck Berry and Scotty Moore on Elvis Presley sides in the ’50s; encountered his first jazz revelation taking in Barney Kessel on the 1957 LP The Poll Winners with Shelly Manne and Ray Brown; experienced his second guitar epiphany hearing Jim Hall’s counterpoints to Sonny Rollins on the saxophonist’s The Bridge; and later bowed to Jimi Hendrix, especially 1968’s Axis: Bold As Love.

In his early days, Abercrombie was more likely to unplug and retreat to his room when he heard further-evolved musicians—saxophonists, pianists, other guitarists—than to charge full-speed into jam sessions unprepared and unable to keep up.

During Abercrombie’s first year at Berklee School of Music in 1962 (eight years before its name was changed to Berklee College of Music), he heard saxophonist Sadao Watanabe, a fellow classmate, practicing Charlie Parker tunes, which crushed him. “I felt terrible,” Abercrombie says. “[I thought], ‘I’ll never be able to play this music. It’s too hard.’ But I stuck it out. I didn’t know what else to do. If that didn’t work, well, I thought I could go home and pump gas. I could give it up and become one of everyone else.”

Not a chance. Determined, Abercrombie dug in, studied heavily, listened intently, practiced vehemently and overcame the urge to retreat. Fifty years after enrolling at Berklee, the 67-year-old Abercrombie is recognized as one of jazz’s most identifiable and adventurous six-stringers. He has enjoyed a profoundly successful career as a leader almost exclusively on ECM Records, including his new album, Within A Song—an homage largely to the music of the early ’60s that made an impact on his young ears—featuring the support team of Joe Lovano on saxophone, Drew Gress on bass and Joey Baron on drums. He pays tribute to Rollins and Hall, Art Farmer, Bill Evans, Miles Davis and Ornette Coleman—artists who were resolute on re-envisioning the tradition.

In the album’s liner notes, Abercrombie writes, “It was this music that spoke to me. When I heard it, it was like finding a new home. The music on this recording is dedicated to all those musicians [who] gave me a place to live.”

After years living in Boston post-Berklee and then relocating in 1970 to a loft space in New York, the amiable and self-effacing Abercrombie today dwells in the country, about an hour from New York by car or train. He’s got a deck for barbecuing, a pool that’s perfect for a summer day, a yard with tall trees and a disheveled downstairs jam-session room scattered with instruments, most of them guitars. Abercrombie seems contently settled yet also ready to pounce onto a new quartet project that’s already in the wings (this time with the same rhythm team and pianist Marc Copeland, a longtime collaborator).

Convinced he wanted to pursue a musical life while still in high school, Abercrombie started poking around at post-graduation possibilities. Two schools he investigated were Manhattan School of Music and The Juilliard School. “None acknowledged jazz, and none accepted guitar as a major instrument,” he says. “Plus, they were looking for students who had super-good grades, which I didn’t, so they were out from the beginning.”

He heard about Berklee from a friend and sent away for a catalog; when it arrived, there on the cover were various musicians hanging around the front steps of the school. One was Hungarian guitarist Gábor Szabó, who had his instrument with him. Abercrombie opened the booklet and discovered there were numerous classes for guitarists. “‘That’s for me, I’m in,’” he recalls. “The requirements were two years of musical experience. Everybody lied. I had classes with guys who couldn’t play at all, and real professional players.” He adds, with a laugh, “Keith Jarrett was there my first year. He came and realized there was nothing they could offer him, so he went off to fame and fortune.”

After a discouraging first year at Berklee, Abercrombie gained confidence, especially through the encouragement of such teachers as Herb Pomeroy, John LaPorta and Jack Petersen (the first full-time guitar teacher and inaugural chair of the guitar department). Abercrombie soon scored a gig with a small band. “It felt good to be a working musician, carrying my guitar down the street,” he says. “It was being on a team, where you don’t quite know what it is but that you’re part of it, you’re in this thing called music.”

Foster was truly a drummer to the stars, including Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins and Joe Henderson.

Jun 3, 2025 11:25 AM

Al Foster, a drummer regarded for his fluency across the bebop, post-bop and funk/fusion lineages of jazz, died May 28…

“Branford’s playing has steadily improved,” says younger brother Wynton Marsalis. “He’s just gotten more and more serious.”

May 20, 2025 11:58 AM

Branford Marsalis was on the road again. Coffee cup in hand, the saxophonist — sporting a gray hoodie and a look of…

“What did I want more of when I was this age?” Sasha Berliner asks when she’s in her teaching mode.

May 13, 2025 12:39 PM

Part of the jazz vibraphone conversation since her late teens, Sasha Berliner has long come across as a fully formed…

Roscoe Mitchell will receive a Lifetime Achievement award at this year’s Vision Festival.

May 27, 2025 6:21 PM

Arts for Art has announced the full lineup for the 2025 Vision Festival, which will run June 2–7 at Roulette…

Benny Benack III and his quartet took the Midwest Jazz Collective’s route for a test run this spring.

Jun 3, 2025 10:31 AM

The time and labor required to tour is, for many musicians, daunting at best and prohibitive at worst. It’s hardly…