Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

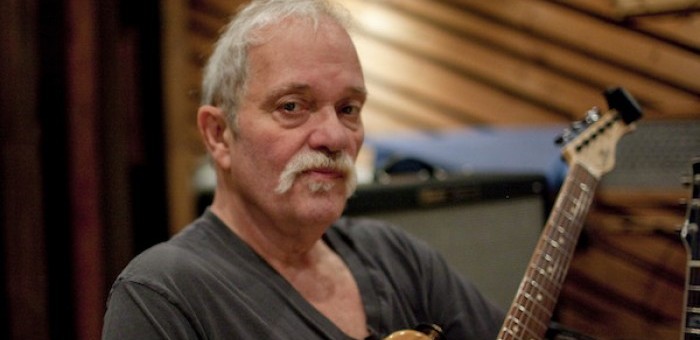

John Abercrombie (1944–2017)

(Photo: John Rogers/ECM Records)In 1975, Abercrombie, DeJohnette and bassist Dave Holland formed the monster post-fusion band Gateway and recorded its eponymous debut for ECM. “Phew, that was such a great band,” Abercrombie says. “The music was so fresh. I was a crazy kid then. We were all like kids let loose in a toy shop. It was like, ‘Take any toy—you won’t get in trouble.’ I had permission to take all kinds of risks. It was the Wild West. One audience member told us that he heard that record and he shaved his head. There were no guitar trios then playing in that free style.” The group recorded two albums, then reconvened nearly 20 years later for two more.

Holland recalls those heady early days. “That band meant a lot in the ’70s,” he says. “We got to explore music that no one else was doing. We had great tours.” As for Abercrombie’s guitar voice, Holland adds, “John has always looked to seek new music. He has great range. And he has such a personal voice on the guitar, which is not easy. Over the years he’s come up with his own sound, approach, phrasing. He can straddle a lot of styles, going into the contemporary field with open-form music and contemporary beats.”

Beginning with Timeless and Gateway, with rare exceptions, Abercrombie has been in ECM’s stable since, playing with a dizzying array of musicians, including a quartet with pianist Richie Beirach, more sessions with Rava, albums with Ralph Towner as well as Jan Garbarek, a trio with Peter Erskine and Marc Johnson, and for the last four albums before Within A Song, a quartet with violinist Mark Feldman.

Abercrombie opted to form a new quartet for the Within A Song sessions, this time with a saxophonist instead of violin. “I felt like that last quartet had run its course,” he says. “I went back and forth with Manfred about this and finally he said, ‘Why don’t you call Lovano?’ I’d played with Joe over the years, but I figured he was just so busy with recordings and touring. Still, I called him up, and he said, ‘Absolutely.’ I knew he would be the best person because he knows the music.”On the new disc, Abercrombie creates a compassionate, very personal reflection on the integral music of his awakening years as a jazz guitarist. Rather than paying tribute to one artist, he zeroes in on songs from albums that influenced him, including Davis’ Kind Of Blue, Rollins’ The Bridge, Coleman’s This Is Our Music, Evans’ Interplay and John Coltrane’s Crescent—all music that Abercrombie says makes for “a celebration of an era when the musicians were stretching the forms.”

“My favorite record of all time is The Bridge,” Abercrombie says. “I first heard it in 1962 at a record store in Port Chester, New York. I saw the picture of Sonny on the cover. He had a strange haircut, jacket and his tenor saxophone. I asked the guy in the shop to play it for me, and the first track was ‘Without A Song,’ with Sonny playing the melody and Jim playing a little counterpoint. Remember the little girl from The Exorcist when her head spins around 360 degrees? That’s what happened to me. And I kept thinking, ‘What are they doing?’ The sound grabbed me, and it was at that point that I knew what I wanted to do more than anything. Those moments, they just happen. You can’t look for them. They look for you, and wham!”

Abercrombie knew he needed to pay tribute to that tune, and he complemented it with his own composition “Within A Song,” which opens the track with an upbeat, dance-like guitar/tenor sax connection. That transforms into “Without A Song,” before returning to the original head.

Abercrombie also includes the Bridge track “Where Are You.” He gives further salutation to Hall by including a take on Sergio Mihanovich’s lyrical song “Sometime Ago,” which was a staple of the quartet Hall and trumpeter Art Farmer co-led (featuring bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Pete La Roca). “Jim was a big influence on me, in the way he played and worked inside of a band,” Abercrombie says. “The Hall-Farmer group was my favorite, especially live.”

Also featured on Within A Song is a nod to Kind Of Blue with a reflective-to-ecstatic rendition of “Flamenco Sketches.” Abercrombie didn’t discover the 1959 album until he was at Berklee: “People were talking about modes while I was still in Barney Kessel-Tal Farlow land and trying to figure out how to play a root-position chord.”

Abercrombie approached the song by taking the form and improvising with it, a lesson he learned when playing with Gil Evans at the Village Vanguard years before. “We were playing ‘Summertime’ and I didn’t state the melody, but improvised around it. After the set, I apologized to Gil for doing that, and he said, ‘Don’t apologize. Who cares? Gershwin’s dead, so you can make your own melody.’”

On “Flamenco Sketches,” Abercrombie and Lovano solo above and below each other. “We’re not comping,” the guitarist says. “We’re playing together without stepping on each other’s toes. It’s more a commentary. That’s the way the entire session worked, which made it such an easy record to do.”

Other tracks recorded in homage to classic ’60s jazz LPs include “Wise One” (from Crescent), the blues-swinging “Interplay” (the title track from the Evans album) and “Blues Connotation” (from This Is Our Music). Abercrombie contributes two originals that he says have nothing to do with the era: “Easy Reader,” a sober waltz with yearning tenor, and the playful “Nick Of Time,” with intertwining guitar and tenor sax lines.

While Within A Song is powered on the front line by Abercrombie and Lovano, the album also trains a spotlight on the rhythm team’s prowess. “Joey and Drew can change on a dime,” Abercrombie says. “They can play the most straightahead or go into the outer limits. They are two guys who are adaptable and ready to change.”

The guitarist has known Baron for a long time. Originally the default drummer of an Abercrombie quartet when the original drummer jumped ship to tour on the eve of a recording session, Baron became “a blessing in disguise,” says Abercrombie, for “his unusual playing that’s so colorful and out of the ordinary. He gets so involved in my music and is full of suggestions and ideas.”

Baron returns the compliments. “John is one of those guys who models an aesthetic of making music that’s somewhat vanished from the scene,” he says. “He’s particularly brilliant in the way he carries a foundation of the tradition from a period, like on the new album where we pay tribute to a time without playing like the people then. When he plays, you can hear the connection to the roots of jazz. Even though he’s not given due credit, he’s opened the door for a lot of people. John doesn’t wear it on his sleeve. He doesn’t lecture. He makes music in the moment, which is a rare trait.”

As for the other half of the rhythm section, Abercrombie appreciates how Gress plays bass in a dependable way that’s also very modern. “Drew is linked to the tradition,” he says. Gress, in turn, values the freedom that Abercrombie brings to a session. “John doesn’t say much about what happens,” he explains. “It’s about the conversations we have, not about agendas or judgment. [Instead], it’s, let’s talk with our instruments. It’s nice to know that still exists.”

Gress feels that Abercrombie’s guitar tone transcends his playing. “He’s immediately recognizable,” Gress says. “He keeps the group sensibility in mind even when he solos. He can really shred on his instrument. He takes chances to break new territory.” Gress adds, “John’s an important musician in the sense that he doesn’t want jazz to become calcified. He’s game for whatever. It’s hard to keep up with the energy he has. I hope I can be like him when I grow up.”

Growing up is a notion that Abercrombie doesn’t appear to subscribe to. He’s still evolving, still making his way. He vividly recalls those days when he felt behind the times, in skills and style. While not outwardly a rule-breaker, the guitarist has quietly made it his goal to subvert the music from the inside—not with a brash blast such as in the early Gateway days, but from within. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…