Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

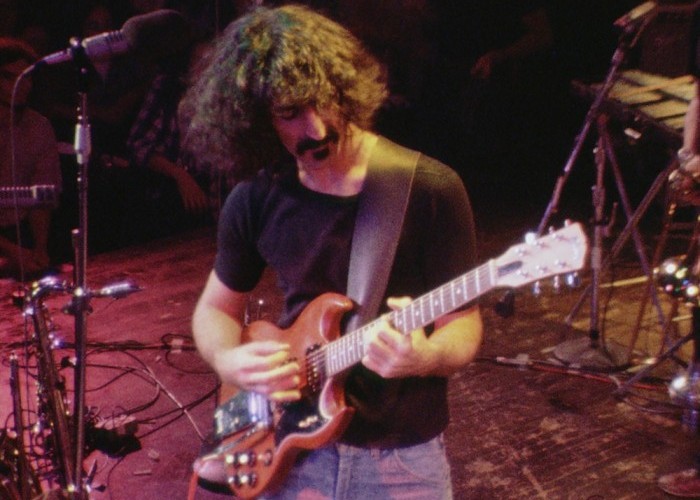

Frank Zappa performs during December 1973 at The Roxy in West Hollywood.

(Photo: Zappa Reords/UMe)Frank Zappa died in 1993, but his career still is going strong with each year bringing new recordings, merch, controversies and commentary.

This year, production company Eyellusion announced a Frank Zappa hologram tour in the near future with early-’70s footage of the guitarist accompanied by former bandmates. Meanwhile, LUNO (iamluno.com) produced a limited-edition Frank Zappa stereo console, complete with turntable, speakers and Zappa whiskey glasses.

More interesting, though, is the release of The Roxy Performances (UMe), a seven-disc set presenting the entirety of the Dec. 9–10, 1973, run at the West Hollywood theater. This year also saw the release of Burnt Weeny Sandwich and Chunga’s Revenge on vinyl for the first time in three decades, both on 180-gram and issued through UMe (universalmusicenterprises.com). These are part of the ongoing collaboration between the Zappa Family Trust and the imprint to introduce new titles and to restore old ones to circulation.

To help overwhelmed Zappa fans cope with this onslaught of new music, academic Charles Ulrich has published a 798-page book, The Big Note: A Guide To The Recordings Of Frank Zappa (New Star, newstarbooks.com), a doorstop if ever there was one. For each of Zappa’s 1,663 tracks on his 100 albums legally released through 2015, Ulrich details the circumstances of the recording session or live performance, the musicians involved, the solos, edits to the track, the original plans for the piece and any arcane reference in the lyrics. This is bolstered by quotes from Zappa or his collaborators about the track, followed by a discussion of where else the song surfaced on other albums and tours.

Accompanying these track-by-track notes are similar descriptions of each album as a whole, sidebars on every musician who toured with the bandleader, sidebars on other interesting characters and topics, plus a long introductory essay. What’s interesting is that, although it presents plenty of pointed opinions by Zappa and his sidekicks, it doesn’t present any by the author.

“Who cares about my preferences?” Ulrich said. “The Big Note is about Frank Zappa, not about me. ... Certainly, I have favorites and not-so-favorites. But I felt readers would be better served by detailed factual descriptions than by critical assessments. Let them make up their own minds.”

Such self-effacing humility is rare in a writer. And it could be welcomed by those who crave information more than analysis, though it could frustrate anyone looking for new perspectives, rather than more data.

The book’s title comes from a Zappa quote recounted in the intro: “Perhaps the most unique aspect of The Mothers’ work is the conceptual continuity of the group’s Output Macrostructure. There is, and always has been, a conscious control of thematic and structural elements flowing through each album, live performance and interview. ... The Project/Object (maybe you like Event/Organism better) incorporates any available medium, consciousness of all participants (including audience), all perceptual deficiencies, God (as energy), The Big Note (as universal basic building material). ... It is not fair to our group to review detailed aspects of our work without considering the placement of detail in the larger structure.”

Ulrich never explains how that is different from, say, the collected music and repeating themes and motifs of George Gershwin, Thelonious Monk or Stevie Wonder. Every composer and performer has a “tell,” as poker players put it, a recurring signature trait. For artists such as Zappa or the Grateful Dead, who present songs in many different studio and concert situations, it can be helpful to take micro looks at each performance and a macro look at the entire body of work.

Ulrich does provide useful insights into Zappa’s methodology as a stage conductor, composer, arranger and sound editor in the introduction. The author’s discussion of the composer’s use of odd meters, nested tuplets, suspended second chords, lydian modes and musical quotations is necessarily technical, but it opens a window on the unpredictable harmonies and rhythms underlying seemingly silly songs.

“The mixture of low-brow humor and high-brow music was intrinsic to much of Zappa’s work,” Ulrich said, “so much so that it’s hard to imagine it any other way. While it may turn off some listeners, others love it. And certainly the mixture of different types of music on his albums exposed listeners to things they wouldn’t otherwise have heard. On Sheik Yerbouti, ‘Bobby Brown Goes Down,’ a big hit in Europe, is immediately followed by ‘Rubber Shirt,’ a xenochronous work superimposing a bass line in 4/4 on a drum track in 11/4.”

That juxtaposition of ambitious music and dormitory-style jokes is omnipresent on Roxy. Zappa was notoriously caustic in his comments about jazz, but he liked to hire jazz musicians who could read, because they were better prepared to handle odd meters, unusual chords and fast passages than most rock musicians. At these Roxy shows, the band behind Zappa was keyboardist George Duke (Cannonball Adderley), drummer Chester Thompson (Weather Report), trombonist Bruce Fowler (Toshiko Akiyoshi), bassist Tom Fowler (Jean-Luc Ponty), percussionist Ruth Underwood (Billy Cobham), saxophonist Napoleon Murphy Brock (George Duke) and drummer Ralph Humphrey (Don Ellis).

Lyrics easily can be deduced from such titles as “The Idiot Bastard Son,” “Hollywood Perverts,” “Penguin In Bondage” and “The Dog Breath Variations.” This would be more enjoyable if the jokes were as funny as Zappa seems to think they are, and if his vocal pitch were as precise as the instrumentation. But some of the instrumental passages are exquisite, especially Duke’s bluesy Rhodes solo on “Cosmik Debris,” Underwood’s lyrical marimba solo on “Uncle Meat” and Zappa’s solo on “Penguin In Bondage.” It would have been helpful if The Big Note had identified such gems in the catalog, but it’s just not that kind of book. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…