Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“You know, I am not as fast as I used to be,” says Foster. “But it’s more fresh ideas. I’m always coming up with new stuff when I practice.”

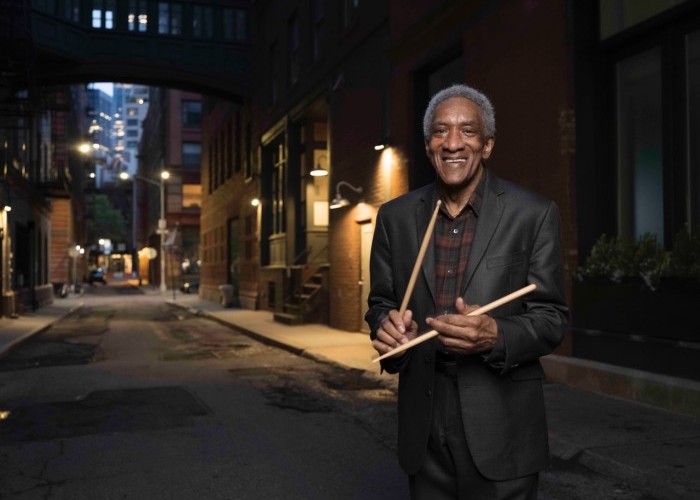

(Photo: Jimmy and Dena Katz)To call Al Foster a student of the drums is an understatement. The 79-year-old master has studied the history of jazz drums, much of it in-person, as he’s speaking of legends like Arthur Taylor, Joe Chambers, Philly Joe Jones, Tony Williams, Billy Hart and so many more with the depth of an artist who has a keen ear and eye as well as the warmth of knowing these legends as friends as well as peers.

Even more impressive is his list of credits as a sideman with Kenny Barron, Miles Davis, Blue Mitchell, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson and so many more.

It seemed fitting to ask another student of the instrument, veteran drummer Joe Farnsworth, to sit down with Foster to discuss his life, musical loves and just a slice of his long, illustrious career for Al Foster’s first DownBeat cover article in honor of his latest release as a leader, Reflections on Smoke Sessions Records.

The following is just a portion of the freewheeling, nearly two-hour interview. It has been edited for space and clarity.

Joe Farnsworth: Believe it or not, in 1988 when I was in college, I was 18 years old, and there was a musician’s union phone book. It had all the musicians in it — Horace Silver, Walter Bishop, Walter Davis, Sonny Rollins — but the two people I was able to call from that phone book were you and Arthur Taylor. And I was able to meet you back then. And you were so kind to me as a kid. So thank you for that, man. You invited me to help take your drums or be like a drum tech. You were just on the road with Herbie Hancock.

Al Foster: Wow. OK, that was 1986.

Farnsworth: I was a freshman in college. So, of all the musicians I called, you were the one that were most kind and most supportive. So, thank you so much for that. Let’s talk about how you feel now, man. How are you doing?

Foster: I’m getting old. You know, I am not as fast as I used to be. But it’s more fresh ideas. I’m always coming up with new stuff when I practice. Because lately, I practice every day — drums, two sets in my living room. I just sit there for a few minutes, you know, almost like, “Whatcha gonna show me today?” I don’t want to play the same stuff. It’s just the way my mind works. I hate it if I keep playing what I know. Show me something I don’t know. I want something different.

Farnsworth: You’re saying that to yourself?

Foster: I’m saying that in my brain, before I even pick up the sticks. I just sit on the drums and look at them. I usually start at 12 o’clock, noon, and it’s been working for some time. I’m still learning it at this age. I’m 79.

Farnsworth: 79.

Foster: Yeah, I’ll be 80 next January. I’m just overwhelmed. My whole career, all the people I played with. You know, sometimes when you do this, you take it for granted like, “OK, I’m playing with Miles, and maybe that’s why other people called me after Miles. I was always insecure. Because I always wanted my own style after Tony [Williams] and Joe [Chambers and Jack [DeJohnette]. I said to my maker, “What about me?” Like, can I be me? I just was brought up differently … a little bit. And then all the people I played with were innovators. I remember in the late ’80s, telling Sonny Rollins, and Sonny probably thought I was turning mad. I said, “Sonny, before I’m 50, I’m going to have my own style.” [Farnsworth turned 50 in 1993.] It was it was getting close to that. And I couldn’t believe I said that to him. You know Sonny, he was like, “OK, OK, Al.” He was probably sayin’, “What’s going on with Al’s brain?” [laughs] When you idolize so many talented musicians, you want to be there, too. I know I wasn’t there as far as being an original, and I’m still working on it.

Farnsworth: I was talking to [drummer] Billy Hart during the pandemic. And he mentioned you. That there was a drum battle with you, Billy Hart and Philly Joe Jones. And Papa Jo [Jones] was the emcee. And according to Billy, Max [Roach] was there and he gave a lecture on how to have your own sound. And as he was speaking, he was tapping on Billy’s tom-tom like, “Sit down and listen to me.” And then Billy said you told him, “If I don’t have my own sound in five years, I’m gonna quit.” And Billy made a deal with you. And he said, “Al did get his own sound” and [Billy] was still trying to get it.

Foster: I don’t remember seeing Max or Poppa Joe. Wilbur Ware was there. I think I was so nervous, I didn’t want to look out the stage. But Philly told me and Billy Hart something that that everyone should use, especially when you’re starting out. He said if the time gets turned around, don’t try to find it. He said, “Whoa, it’s no time.” And me and Billy looked at each other and said, “Wow, he’s right.”

Farnsworth: Do you remember how Philly played that day?

Foster: He played great. Yeah, Philly Jones is always Philly, regardless. He’s so hip, man. And just the way he was chopping, you know? [vocalizes the sound of the drums] Absolutely, a really awesome drummer. I used to see him at Gretsch Drum Nights, Charlie Persip, Mel Lewis. Mel Lewis saw me on a Monday night, you know, with all of my drugs. And he said, “That’s gonna catch up with your as you get older.” And he was right, you know? Yeah, he said it in a real nice way, too.

Farnsworth: I met him one time, I played at my brother’s senior recital at North Texas State. And I said “hi” to him, and the only thing he said to me was, “You played way too effing loud. And then kept walking. [laughs] Back to the present day. During the two years of COVID, were you practicing the whole time?

Foster: Yeah.

Farnsworth: And you sit there and say to the drums …

Foster: No, this started maybe more this year. Me sitting there thinking. So, you know, I don’t want to sit down and play what I’ve been playing for years. And like Lester Young, I don’t go there. [laughs] I’ve been listening to some of his interviews. You need to.

Farnsworth: Did you ever see him?

Foster: I never seen him. I never met him, and I wish he would have lived long enough just for me to see him play. And Billie Holiday was another one I missed. I cried. I was 16, I think, when she died. I cried like a baby for weeks putting on her records. Too sensitive, actually.

Farnsworth: That’s what makes you so great, because you’re so dynamic.

Foster: You know, even happy things can make it happen, you know, like some of the cuts on my new record make me cry.

Farnsworth: Let’s talk about your new record. Who’s on that?

Foster: Well, the bass [Vicente Archer], I met him at the studio. Chris Potter, he was in my band in ’94 or ’95. He was great. He sounded so wonderful. Nicholas Payton, I played with at Smoke just before the pandemic. Great. He sounded unbelievable. And Kevin Hayes used to play with me in the late ’90s, early 2000s, genius type piano player. And the way he arranged my two songs — I have three songs on the album but he arranged two of them. I didn’t know that he was gonna have how many notes for the two horns just playing the melody. Just blew my mind, man.

Farnsworth: This was some of the best playing you’ve done on record, isn’t it?

Foster: I’m proud of it.

Farnsworth: How did you maintain your strength through this whole two years off of playing?

Foster: Well, I just practice. Yeah, it didn’t bother me at all.

Farnsworth: Did not playing gigs at all bother you?

Foster: The last gig I had was here [at Smoke]. The end of February. And I had a lot of gigs after that, and all that stuff was canceled. But I get a nice check from Uncle Sam because I’m an old man. [laughs]

Farnsworth: Do you still have the same feeling like you used to have back in the ’80s, or the ’70s?

Foster: Oh, yeah. I really enjoy playing. But I just came in so laid-back, not knowing what to expect. And I just played it like that. And I would tell you [if] I had either a wine or whiskey, I don’t remember, you know. It’s dinner time, and I had a long break, and then I forgot about the new Al Foster and went back to “Noisy Guy.” [laughs] It’s true, bro. Come on, man. I have to be honest about me. Everything is not Mr. Wonderful. You know, it’s not like Joe Chambers. To me, Joe is like a perfect drummer.

Farnsworth: Are you talking about his cymbal beat?

Foster: Less is more. Oh, I used to copy that cymbal beat to death. Miles even said — and made Joe Chambers feel good about this — Miles said [imitating Miles Davis’ raspy voice], “I don’t wanna hear none of that Joe Chambers shit.” So, I told Joe, when we were having lunch together in Europe, and Joe smiled. He loved it. Because he used to hear me playing his beat in the ’70s. He’s a wonderful drummer. Great piano player. Good musician. Yeah, yeah, I like him a lot.

Farnsworth: Let’s go back to early years when you were growing up. What was that like? Where did you grow up?

Foster: Harlem, 140th and Amsterdam, right across the street from City College.

Farnsworth: Brothers and sisters?

Foster: Yeah. I have an older brother. He played congas. One year older than me. Capricorn, too, Jan. 9, 1942. I’m ’43, born on the 18th. So, my sister was born in ’48. I was 5 when she was born. She was born in November. January, two months later, I turned 6 years old. And two younger brothers, one was born 1950, the same day, June 12, as my wife, Bonnie. He played tenor for a while. But they went to public school, my sister and two younger brothers. It was different. In the streets with the gangs. But I came home from school, sat at my drum set, especially when I heard Max Roach. I was about 12, maybe 13.

Farnsworth: Were you already playing drums at this point?

Foster: Oh, yeah. My aunt said when I was 3, I was banging on pots and pans. And first, second grade, all through the school years.

Farnsworth: Pots and pans.

Foster: Banging like this. [demonstrates] I had pencils. “Aloysius,” the nuns yelling, for real. I didn’t know why they were so upset. So, I was banging on my mother’s pots and pans. My great aunt, my mother’s father’s sister, brought me a practice pad when I was about 5 or 6. And they tell me I played when they were on a boat ride, and I played with the Count Basie band when I was s7. I don’t remember. My aunt was supposed to have a picture.

Farnsworth: You actually played with Count Basie?

Foster: I guess they let me play a little solo.

Farnsworth: Was that with Sonny Payne, maybe?

Foster: No. That would mean it was in the ’40s when that happened. I was born in ’43, so this was in the early ’50s. The first time I saw Count Basie live was at the Apollo Theater with Sonny Payne. Unbelievable. And when I was at Minton’s with Blue Mitchell, he came in and sat in on my Slingerland set. And he sounded good, but he was, you know, different with that kind of music. Art Blakey came in and sat in at Minton’s every time he would go with somebody. And Jack DeJohnette sat in. He just came in off the bus from Chicago. I just met him. I didn’t know if he could play. But it was unbelievable, man. I mean, I never understood Jack’s playing, but the swing is there.

Farnsworth: What was your first “name” gig that people came to see, like your arrival?

Foster: Well, I would say Blue Mitchell because we would go play Minton’s there. And one time I was filling in and Donald Byrd and Kenny Dorham were both standing near the drums, you know, and when we finished a tune, one of them said, “You sound like A.T. [famed drummer Arthur Taylor].” Man, I felt so good about it, I looked the other way. I was probably “doh, doh, chu, dohn, dat, dat, dat, dat at, boom, boom, boom” [imitates a Taylor drum pattern]. A.T. had some slick little moves.

Farnsworth: So, even at early age, you were playing great.

Foster: Well, I was kinda playing like A.T. and somewhat like Max.

Farnsworth: When was the first time you met Art Taylor?

Foster: That’s another great story. I’m practicing in my apartment, and I look to my left, it’s my mother’s bedroom. I was in the living room. Big mirror is in front of me. I never met A.T. before, never even seen him play live. I see this light-skinned guy. Heavy mustache. But my aunt, my mother’s sister, was in front of him. I jumped up, and he said, “Play, sit down and play.” And he’s sitting on the couch just watching me. I was playing to something from Max Roach, from one of Max’s records.

So, we became friends then, and my great aunt lived in the same building on the same floor as A.T. He was still living with his mother. He’s in his 30s. When I went to see my aunt, [I’d go to] A.T.’s. His mother, she loved me. Even when A.T. wasn’t there she was like, “Come in, come in.” She was showing me pictures of when they were teenagers and Sonny [Rollins] and the band. Yeah, it was great, man.

A new [Art Blakey] record came out, and I went by that night. And [A.T.’s mom] let me in, and I went to T’s room. And the new record was on, and he just yelled, “Bu.” [Short for Blakey’s Muslim name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina] I said, “Whoa.” He was really in love with Bu. He was a good person.

Farnsworth: Who were the guys you were a fan of, who you wanted to play with?

Foster: The ones that I did play with.

Farnsworth: Miles.

Foster: No, no, it wasn’t Miles. It was Sonny Rollins, early Sonny Rollins. I bought Max Roach +4 — that did it!

So they didn’t have the Max with Clifford Brown album [at the record store]. I see Max sitting down with these big guys behind him, you just see their backs. So, I bought it. Sonny Rollins did it to me, man. I fell in love with Sonny’s playing. I bought a saxophone in 1970, a Mark VI Selmer. I had just worked at the Apollo with Hugh Masekela. So I bought me a tenor, and I’m trying to play that lyrical stuff like, you know, I’m talking about early Newk [Rollins’ nickname], all the ’50s and ’60s recordings.

Farnsworth: And when did you meet Sonny?

Foster: You want to know that story? [laughs] Sonny Rollins called me on a Sunday in 1969, and asked me if I can play the Vanguard with him.

Farnsworth: Never met him before?

Foster: Never met him.

Farnsworth: Wow.

Foster: I said, “Sure.” He asked me if I could come to the Vanguard in the daytime to go over the tunes. I get down there with my bass drum and snare drum. Sonny’s back is to me, but he’s near the where the phone is in the Vanguard. I’m lugging my bass drum and shit. He never turns around. When I got everything up, and he heard me hittin’ the cymbal and the snare, he turned around [doing his best Sonny impersonation], “OK. How you doing, Al?” And he just went into this straightahead tune. And it was cool. He asked me, “Do you know how to play a calypso?” I said, “I think so, yeah,” because I don’t know what he’d like.

Farnsworth: I heard that you were the only guy that he liked that knew how to play a calypso. How did that come about?

Foster: Maybe. I don’t know. From Blue Mitchell, my first album. Even Louis Hayes asked me what was that guy doing on the cymbals? It was on the jukebox at Slugs. And Louis came over to the table. I was just hanging and, yes, I felt so good.

So, Sonny says OK after the calypso. Tells me what time to be at the gig Tuesday night. I don’t know that Tony Williams is playing with Lifetime [also that night]. We knew each other. Always nice to me. But I was nervous. Albert Dailey was on piano, great piano player. My idol on bass, Wilbur Ware. I think he’s the one that told Sonny to hire me. I knew Wilbur, he lived in my neighborhood — always calling me, you know, to borrow a couple of dollars to get wine and, probably, other things, you know.

I was raising the kids by myself at that time. Do the first gig Tuesday night, and Wednesday night. Thursday, Sonny called, he broke my heart. He said, “Al, listen, man, I want to try something different tonight, OK, man?”

Then, Wilbur calls and tells me he got fired. I said, “Whoa.” Anyway, Sonny told me come by Sunday and he’d pay me for the two nights. I said, OK. I couldn’t believe the new bass player and drummer. [The drummer] was a policeman, I can’t remember his name.

Anyway, he paid me, and I went back to the Vanguard to see somebody the following week. [Somebody] told me that Tony Williams said when I was playing, “Al’s gonna get fired.” Because he fired Tony, too. He fired Joe Chambers.

Farnsworth: But then you went back with him.

Foster: Nine years later, he just called me, and asked if I could go to Europe. No rehearsal or nothing, July 1978. And, he was super nice to me. Giving me solos when I’m trying to take it out. Smiling. I was on the road with Joe [Henderson] in the ’90s. And critics would yell to me — it’s like at a festival, where everybody gets on the same bus from the hotel — “Did you know Sonny Rollins said you were the last of the great drummers?” Twice I was asked that. Of course, no, because he never said that to me. But I worked with him from that time on, all the way, even after I got in trouble. I played with him after his wife died, yeah.

Farnsworth: What’s he like off the stage?

Foster: He is cool. He was almost like Miles to me. He called me all the time. Yeah, Newk is cool. One of his tunes is on the album, and I hear he lives on my street now — so, when it comes out, I’m just gonna go take it to him. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…