Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

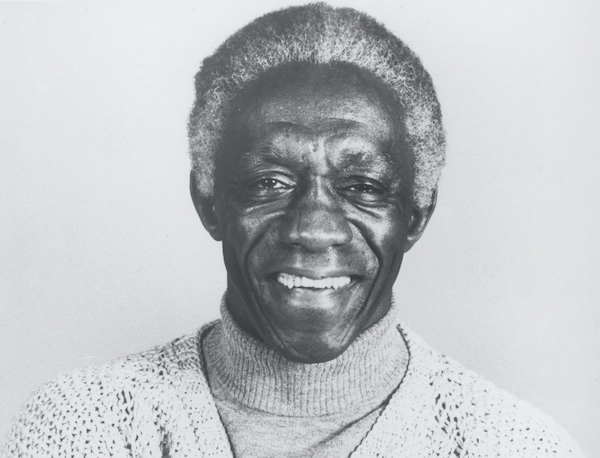

Art Blakey (1919–1990)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)No drummer more palpably imprinted their sonic identity and aesthetic principles on the soundtrack and culture of late 20th- and early 21st-century jazz than Art Blakey.

For 35 years, Blakey’s vehicle was the Jazz Messengers; their message remains as vibrant as ever in the year of the leader’s centennial. Tribute bands led by acolytes Ralph Peterson, Carl Allen and Lewis Nash continue to channel Blakey’s mojo on Messenger repertoire by notable alumni such as Benny Golson, Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Curtis Fuller and Bobby Watson.

New releases help extend Blakey’s legacy. Our Father Who Art Blakey: The Centennial (Summit) is the second big band homage by Valery Ponomarev, a trumpeter on numerous Messengers albums between 1977 and 1980. And on Children Of Art (Capri), guitarist Joshua Breakstone (not a Messenger) interprets tunes by ex-members.

Labels, too, are capitalizing on Blakey’s brand. Austria’s In+Out Records is reissuing the long-out-of-print The Art Of Jazz, documenting Blakey’s 70th birthday concert in Leverkusen, Germany, by a large ensemble that mixed the contemporaneous 1989 Jazz Messengers with a cohort of Messenger immortals and Blakey’s old friend Roy Haynes, who propels much of the proceedings. In early 2020, Blue Note plans to release Just Coolin’, a previously unissued studio date from March 8, 1959, with the same personnel—Morgan on trumpet, DownBeat Hall of Fame inductee Hank Mobley on tenor saxophone, Bobby Timmons on piano and Jymie Merritt on bass—who made the classic live album At The Jazz Corner Of The World five weeks later.

Blakey’s five-star drumming was the core of his immense footprint. “Art could reach inside your emotions,” Golson said on WKCR in 1996. “There was no wasted effort when he played. It was meaningful, logical and sounded fantastic—the epitome of swinging. His style was such that you didn’t want to hear or play with any other style.”

The day after Blakey died, Max Roach, who wasn’t predisposed to hyperbole, told The New York Times: “Art was an original. He’s the only drummer whose time I recognize immediately. His signature style was amazing; we called him ‘Thunder.’ When I met Art on 52nd Street in 1944, he was already playing polyrhythms independently with all four limbs. He was doing it before anybody was.”

Peterson, the last drummer to share the bandstand with Blakey, recently elaborated on the characteristics that differentiated his mentor from generational contemporaries like Roach and Haynes. On the previous evening at Manhattan’s Jazz Standard, he’d led the Messenger Legacy Sextet, including alumni Brian Lynch (trumpet), Bill Pierce (tenor saxophone), Robin Eubanks (trombone) and Essiet Essiet (bass) through two rousing sets. As on the 2019 release Legacy Alive (Onyx)—with Watson on alto saxophone and ex-Messenger Geoffrey Keezer on piano—they projected the admixture of primal energy, intellectual clarity, high science and unrelenting swing that informed the elite Jazz Messengers editions.

“The size of Art’s beat is one thing,” Peterson said. “The strength of his hi-hat is another. But conceptually, it’s how he’d set up phrases and ensemble sections—big band drumming in a small group setting. Not that he was constantly coming up with new things to play, but his placement and timing, his sense of drama and theater within the framework of the music, were always fresh, contemporary and in the moment. When you think about all the music he played from memory, the amount of brainpower could probably power a small city.”

“He was a master of getting to the listener’s ear what he was feeling inside,” said Kendrick Scott, who has absorbed Blakey’s precepts through a long association with trumpeter and Messenger alumnus Terence Blanchard. “His Gretsch drums were the optimal sound for jazz; his vocabulary is baked into the lexicon of jazz drumming. You can’t not go through Art Blakey if you want to play jazz drums.”

Former Messenger Branford Marsalis praised Blakey’s “ear for melody and photographic memory,” which he applied toward establishing an apropos drum part for every tune.

“I’d have an idea of what I wanted when I brought something in, but Art played it the way he felt it, and it worked,” pianist Donald Brown said. “His mix of patterns made you know it was Art Blakey. His press roll sounded like a rubber band being stretched—when he released it, it intensified the groove.”

Equally consequential to Blakey’s legacy are his contributions as a bandleader and teacher, as Roach implied by stating, “Art was a great man, which influenced everybody around him.”

From 1955—when Blakey and pianist Horace Silver co-led the inaugural Jazz Messengers with Mobley, trumpeter Kenny Dorham (replaced in 1956 by Donald Byrd) and bassist Doug Watkins—until his final, 1990 unit with Lynch, Keezer and Essiet, he recruited cream-of-the-crop young improvisers with strong compositional skills, channeled their individualism into serving the group sound and molded them into leaders.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Dec 11, 2025 11:00 AM

DownBeat presents a complete list of the 4-, 4½- and 5-star albums from 2025 in one convenient package. It’s a great…