Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

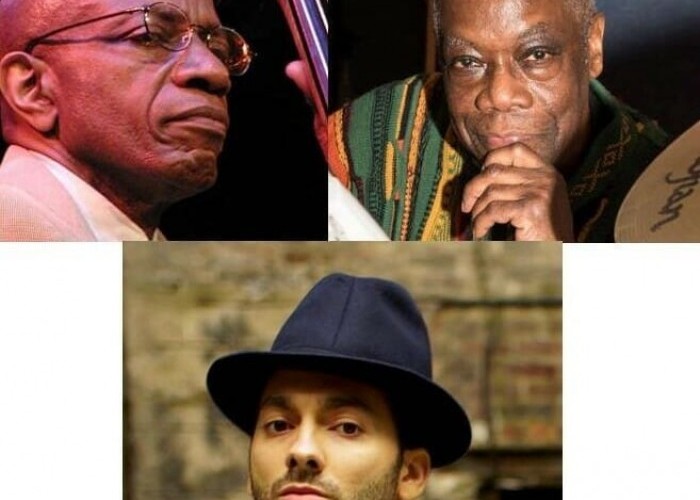

Reggie Workman, Andrew Cyrille and David Virelles wasted no notes.

(Photo: Bang On A Can)When the influential “new music” presenting organization Bang on A Can debuted in May 1987 with a 12-hour, 28-piece concert in an eighth-floor Soho loft, an interested listener could hear every performance on the bill, be it John Zorn’s “Roadrunner,” a scratch-improvised solo trombone recital by George Lewis, a two-piano version of Stravinsky’s “Agon,” and other works by the likes of Milton Babbitt, Pauline Oliveros, George Crumb and Steve Reich,

Such completism was impossible on the weekend of April 29–May 1, when Bang On A Can presented its first Long Play Festival, comprising over 60 concerts by a racially and gender-diverse cohort of cutting edge practitioners of multiple genres at seven venues within walking distance of each other in downtown Brooklyn and Gowanus.

On April 30, this writer’s path began in Gowanus, a developing neighborhood near Brooklyn’s Barclay Center, at Public Records, situated in a Gothic Revival building that served as ASPCA’s Brooklyn headquarters from 1913 until 1979. Square, low-ceilinged, well-baffled, it was a perfect space to hear the resourceful, virtuosic Attacca Quartet, whose 50-minute mash-up set included acoustic adaptations of electronic dance pieces by Flying Lotus, Anne Muller and Louis Cole from their recent Michael League-produced album, Real Life (Sony Classical), followed by more “conventional” repertoire – two sections of Philip Glass’s Third String Quartet, and a haunting narrative work by Paul Wiancko titled “Benkai’s Standing Death.”

Ten minutes down the road at Littlefield, a popular music bar that occupies a one-time textile warehouse, pianist Kris Davis and bassist Dave Holland played their first-ever public duo. They launched with Eric Dolphy’s “Les,” each uncorking blistering solos, then addressed each other’s tunes over a free-flowing, uninterrupted 40-minute span. Davis’ freshness and energy, her ability to use real-time piano preparation to morph organically from one sonic environment to another and consistently postulate fresh ideas, spurred the 76-year-old maestro to delve deep into his bag of extended techniques, free-associatively generating an array of harmonics, overtones and percussive effects while sustaining melodic flow, as he did when he played with Sam Rivers’ tabula rasa trio during the 1970s. Hopefully, many more Davis-Holland encounters — and perhaps a recording; both have labels — will ensue.

Back at Public Record, a large crowd assembled to hear Occam X, a composition for solo trumpet (Nate Wooley) by nonagenarian French synthesist Eliane Radigue predicated on Wooley’s painstakingly calibrated gradations of pitch and sound-silence juxtaposition, which were blurred and obscured by the whirr of the refrigerator behind the bar.

Then, back at Littlefield, trombonist Craig Harris presented an under-rehearsed suite for piano (Yayoi Ikawa), bass (Melissa Slocum) and a string quartet including violinist Sara Caswell. The pace was lugubrious until the fourth piece, “Wild Seed,” dedicated to Afrofuturist science fiction author Octavia Butler, when Ikawa and Caswell lifted the set out of the doldrums with sparkling solos; Harris — who’d previously seemed preoccupied by the group’s disorganization — responded in kind. He sustained that intensity on the last two pieces, complemented by Caswell’s poignant solo on “First World” (for the late poet and Harris colleague Sekou Sundiata) and Ikawa’s torrential inventions on “”Mr. Lovejoy” (for the late baritone saxophonist Hamiett Bluiett).

After a brisk 15-minute walk north, I arrived in the spacious lending library room of The Center For Fiction, catty-corner from Brooklyn Academy of Music, where tubist Marcus Rojas, a shape-shifting genre-hopper and purveyor of extended techniques par excellence, put forth an entertaining, thought-provoking solo concert. Rojas traversed the tuba’s full registral range, created call-and-response between voice (vocalese) and instrument, told engaging stories about teachers and mentors who set him on his path.

I could have hightailed to Littlefield to hear a flute-voice duo by Nicole Mitchell and Fay Victor, and then hustled to Public Records for a solo performance by vocalist-composer Pamela Z (or, for that matter, stayed at the Center For Fiction for a solo bassoon recital by Maya Stone). But I opted to stroll to Roulette Intermedium, five minutes away where Reggie Workman at 84, Andrew Cyrille at 82 and David Virelles at 38 played a compellingly elegant, creative set of compositions by the two elders, who played with creative clarity, focus, vigor, and dialogical spirit – and wasted no notes.

I stayed at Roulette for a think-as-one performance by the Vijay Iyer Trio (Linda May Han Oh, bass; Tyshawn Sorey, drums) — a continuous suite of several Iyer compositions that was far more florid than the performance that preceded it but every bit as detailed and focused. Iyer played with characteristic kinetic, terpsichorean spirit, propelled by Oh’s indomitable grooves and Sorey’s contrapuntal rhythm-timbre sound-painting that commented on the flow.

The finale of Long Play’s debut season transpired Sunday, May Day, at a packed Brooklyn Academy of Music, where Denardo Coleman masterminded and played drums on a concert intended to demonstrate that his father, Ornette Coleman, was completely on-point in titling his first (1959) album for Atlantic Records, The Shape of Jazz To Come.

The concert proved his point; it was an important event that deserves its own review. Suffice to say that Harris (“Peace”), Mitchell (“Eventually”), Pamela Z (“Lonely Woman”), Carman Moore (“Congeniality”), Nick Dunston (“Focus on Sanity”), David Sanford (“Chronology”) and Denardo himself (“Ramblin’” from Change Of The Century, also 1959) contributed phantasmagoric, cogent arrangements that interrogated and transformed the iconic songs without diluting their essence. The charts stretched the superb 20-piece Bang On A Can Orchestra (Rojas, Stone and Coleman’s long-time acoustic bassist Tony Falanga were members), which — under the expert ministrations of conductor Awadagin Pratt — rose to the challenge. The orchestra both dialogued with and complemented an inspiring sextet (“Ornette Expressions”) with veteran Coleman alumni James “Blood” Ulmer on guitar and Jamaaladeen Tacuma on electric bass; the wizardly Jason Moran on piano; and youngbloods Lee Odom (alto saxophone) and Wallace Roney Jr. on trumpet.

Kudos to sound engineer Andrew Cotton, who maintained pristine balance — you could hear every instrument. Kudos to Bang On A Can for evolving with the times. Hopefully, the proceedings were documented for posterity, as an example of what can be accomplished when creative music intersects with this level of infrastructure. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…