Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

In Memoriam: Gordon Goodwin, 1954–2025

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Roy Babbington first recorded with Soft Machine on Fourth in 1971. The bassist is part of a revamped line-up that’s released Hidden Details (MoonJune).

(Photo: Peter Hartl)Soft Machine released Third in 1970, the same year Miles Davis issued Bitches Brew. What began as a trendy psychedelic rock band had become a trailblazing jazz-rock outfit. But Soft Machine’s transformation foreshadowed a series of stylistic and personnel changes that soon were to come.

Roy Babbington joined Soft Machine, playing double bass on Fourth. And with the departure of drummer Robert Wyatt shortly after that, the 1971 album marked the final recording of what some consider the band’s most influential line-up. Babbington played on the next record and eventually replaced bassist Hugh Hopper on 1973’s Seven, and stayed on until the band’s penultimate record in 1976.

Now, 50 years after the release of the influential English jazz-rock band’s self-titled debut, Babbington and former Soft Machine members have released Hidden Details (MoonJune). It takes cues from the band’s classic line-up, but nods at grunge and electronica as well. Babbington discussed with DownBeat all the changes that have taken place during his time in Soft Machine, as well as the emergence of a new sonic direction.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

You succeeded Hugh Hopper as Soft Machine’s bass guitarist. Was he still a presence in the music even after leaving?

Hugh Hopper, for me, was one of the first bass guitarists that actually had a recognizable personality on the instrument. At that point in time, I don’t think the bass guitar was considered a jazz instrument. An awful lot of double-bass players decided to buy a bass guitar simply because it was portable. There was also a degree of demand for it, because of popular music, but there was a naiveté to players that came on to the scene. Most double-bass players that went on to bass guitar used to play it almost like a swing instrument. I thought, well that’s stylistically wrong.

Hugh’s effects on the bass were always important to me. I’m not trying to copy what Hugh does, I’ve got my own range of effects now, but I probably wouldn’t have gone in that direction at all had it not been for his demonstrative playing. That word, “demonstrative,” is not quite the right adjective perhaps, but you’ve got the word demon in it and, quite frankly, he was quite a bit of a demon on the instrument. Trying to play things like “Facelift” ... God, that’s difficult. There’s still a chunk of it I have to take down an octave, because I daren’t try it where he’s playing. It’s the kind of thing where you have to have the eye on the instrument the entire time.

Out of the players on Hidden Details, you’ve been a part of Soft Machine the longest. How has it changed over the years?

My favorite version of Soft Machine was the one that recorded the fourth album. I did enjoy Six as well; I didn’t enjoy Fifth so much. But the band with Elton [Dean], Hugh [Hopper], Robert and [Mike] Ratledge really was a steaming unit.

By the time I joined, Elton had gone. My first album with the fresh band was Seven. I rather enjoyed doing that album, even though it doesn’t seem to be the most popular. Hugh had made a statement that they were determined as a band to never have a guitar in it. But after Seven, we realized that there just wasn’t enough soloist steam in the band. It needed another voice. And of course we found Allan Holdsworth. In a sense, that was where the band kind of changed direction.

What changed around that time?

I think if you listen from Seven to Bundles to Softs, Soft Machine kind of lost its way. After Allan Holdsworth, as good as that band was, it kind of seemed to fizzle away. I know that Mike wasn’t very happy. We used to play backgammon a lot when we were on tour, and you know he just felt exhausted with it all. He felt he had no more to offer. As a result, it kind of became Karl [Jenkins who took the lead]. As interesting as his writing was, it didn’t have the same kind of angular spirit of Third or Fourth. It wasn’t quite so daring.

When Alan left, it needed someone to fill the hole. Very fortunately, John Etheridge came along; he was virtually unknown at the time. Etheridge always says when he joined the band, nobody was talking to each other. His arrival was a delight for me, because I had someone to talk to, someone to visit art galleries in Italy with. He brightened up the atmosphere personally.

What excites you most about Hidden Details?

I feel that it’s the first time we’ve actually encapsulated the spirit that existed around about the time of Fourth. There’s a vibe within the music now. Of course, it’s all different players, but the combination of guitar and saxophone is kind of almost like an American jazz quartet front. The two tracks that stand out to me are the title track, which is saxophonist Theo Travis’, and John’s “One Glove.” Both are absolute treats. The surprise when the bridge section comes with the chord change on “One Glove” makes me smile; it’s lovely. The angularity of the melody lines on both of those tracks does the job. It’s a pleasure to be involved. DB

Goodwin was one of the most acclaimed, successful and influential jazz musicians of his generation.

Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Nov 13, 2025 10:00 AM

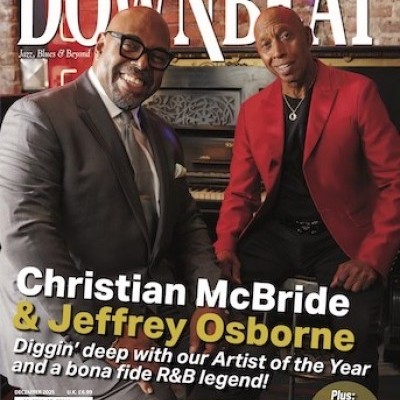

For results of DownBeat’s 90th Annual Readers Poll, complete with feature articles from our December 2025 issue,…

Flea has returned to his first instrument — the trumpet — and assembled a dream band of jazz musicians to record a new album.

Dec 2, 2025 2:01 AM

After a nearly five-decade career as one of his generation’s defining rock bassists, Flea has returned to his first…

“It’s a pleasure and an honor to interpret the music of Oscar Peterson in his native city,” said Jim Doxas in regard to celebrating the Canadian legend. “He traveled the world, but never forgot Montreal.”

Nov 18, 2025 12:16 PM

In the pantheon of jazz luminaries, few shine as brightly, or swing as hard, as Oscar Peterson. A century ago, a…

Dec 11, 2025 11:00 AM

DownBeat presents a complete list of the 4-, 4½- and 5-star albums from 2025 in one convenient package. It’s a great…