Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

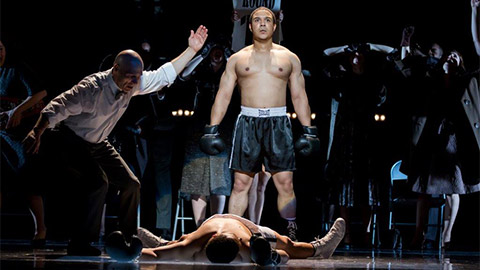

A scene from the opera Champion, which made its East Coast premiere March 4 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

(Photo: Courtesy the Kennedy Center)In Barry Jenkins’ Oscar-winning movie Moonlight, one of the most defining moments occurs toward the end of the second movement. The movie’s central figure, Chiron, had just been brutally beaten by his high-school friend and crush, Kevin, who was encouraged to carry out the heinous deed by Terrel, a bully who insistently taunts Chiron with homophobic slurs. Chiron, leery of talking with the school administrators, reaches a boiling point, and takes things into his own hands. With bloody bruises still noticeable on his face, he marches through a school classroom, picks up a chair, and smashes it across Terrel’s back. Afterward, Chiron is hauled off into a police chair before remerging in the movie’s third act as a hardened drug dealer nicknamed Black.

A similar pivotal moment happens in Terence Blanchard and Michael Cristofer’s poignant opera, Champion, which premiered in St. Louis in 2013 and made its East Coast premiere on March 4 at Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center. Like Chiron, Champion’s main character Emile Griffith struggles with his sexual orientation. Unlike Moonlight, however, the opera is based on a true figure.

Griffith was a world champion welterweight boxer who migrated from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, with earlier aspirations to be a hat maker and possibly a singer. He reluctantly became a boxer after his boss, Howie Albert (played by Wayne Tigges) at the hat factory noticed his athletic physique and pushed him toward the profession. It’s another instance of hardened hyper masculinity being thrust upon a black person. During a weigh-in, before a crucial boxing match between Griffith and former welterweight champion Benny “The Kid” Paret (Victor Ryan Robertson), the protagonist withstands insults from Paret, who constantly hurls the word maricón, a derogatory name for a gay man.

In the March 24, 1962 match, Griffith knocks Paret out in the 12th round and wins the champion title. But the win is cursed. After the match, Paret was rushed to the hospital, where he fell into a coma and died 10 days later.

The haunting of that moment, as well as other psychological baggage associated with hyper-masculinity, drive much of Champion, which opens with an older Griffith—superbly portrayed by Arthur Woodley—struggling with dementia while being cared by Luis (Frederick Ballentine). Griffth’s search for redemption and his perseverance against institutionalized racism and homophobia serve as Champion’s main theme.

Through flashbacks of Griffith’s journey from St. Thomas to New York City, his tormented rise and fall in the boxing field, his short-lived marriage to Sadie (Leah Hawkins) and his dicey relationship with his mother Emelda Griffith (the wonderful Denyce Graves)—who abandoned him and his six other siblings—the storyline of Champion triumphs oftentimes when the music and libretto falter.

After scoring numerous movie scores—notably for Spike Lee—Blanchard already brought an awareness of creating music that underscores visual narratives. Opera offers a different challenge because the script is mostly sung. By moving from orchestral to blues to jazz to Caribbean rhythms, Blanchard’s music certainly accentuates the contemporary nature of Champion, as do Allen Moyer’s colorful multimedia set designs and James Schuette’s snazzy costumes. Oftentimes, such as during Griffith’s vibrant recollections of St. Thomas and his rendezvous at sleazy bars like Hagan’s Hole, it’s tempting to want the music, singing and dancing to break free in a musical frenzy.

But Champion isn’t a Broadway musical; it’s an opera. The movement lags in certain points. And Blanchard’s orchestral dissonance and dank chords can certainly disorient, especially during moments that should otherwise be jovial. Such was the case when a younger Emile (Aubrey Allicock) sings of his love for making hats while still in St. Thomas. Even with Séan Curran’s carnivalesque choreography and danceable rhythms, there’s a foreboding heaviness to the music. The most notable occurrence of this comes during a scene in which Griffith ventures in a gay bar. Perhaps the music’s immensity is used to underscore the emotional baggage that Griffith carries throughout the opera, while the sharp, dissonant chords at times are used to emphasize the debilitating effects of dementia.

Interestingly though, it’s not Woodley or Allicock who delivers the most memorable song performance; it’s Graves, who during the second act sings a ruminative aria duet with bass as she depicts a mother, dejected by Griffith’s simmering frustrations, reminiscing about her life in St. Thomas and regretting her life choices.

Whereas the pacing of Champion sometimes feels sluggish (even during its most kinetic moments), Cristofer’s libretto spikes up the momentum. Certainly poetic, the libretto doesn’t shy away from using provocative language when dealing with masculinity, sexuality and shame. During the scene in which Griffith picks up a male trick, Cristofer dives into realm of sadomasochism as Griffith pleas for pain via intercourse. It’s the moment soon after, when Champion tells the story of Griffith getting gay bashed by a group of thugs that the main character utters the opera’s most memorable line: “I killed a man and the world forgave me, I love a man and the world wants to kill me.”

Champion does end on heart-warming final note, when a trembling older Griffith encounters Paret’s son, Benny Paret Jr., who looks strikingly like his father. After carrying the weight of regret for decades and not being allowed to visit his opponent during his final days in the hospital, Griffith asks his son for forgiveness.

Like the closing scenes of Moonlight, in which there’s a reunion and embrace between Chiron and Kevin, the best friend who betrayed him, Champion closes with a similar tone. But for Griffith, the more important reconciliation occurs between him and his inner demons. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…