Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

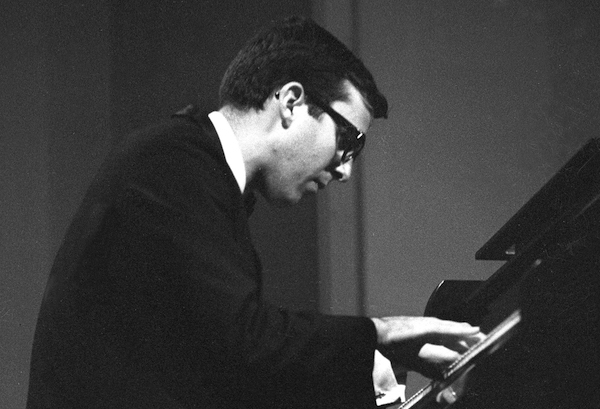

Recently unearthed trio recordings of Bob James from 1965 find the keyboardist and composer working in a surprising mode.

(Photo: Tom Copi)“As a result of getting a job like that with somebody of her stature and knowing what was expected of me, it probably was the first major thing that started to shift my interest away from the avant-garde,” James said. “Because that was a steady job, and working for her was playing standards and trying to swing as hard as I possibly could to justify having that gig.”

James stayed with Vaughan through 1968, and in 1969 he caught a major break when Jones, who had originally met James in 1962 at the Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival, introduced him to producer Creed Taylor, who recently had launched his CTI label. Jones was working on his first CTI album, Walking In Space, and he recruited James for the sessions.

“Whenever possible, Quincy would give me a nod of recommendation to meet different people, and one of the biggies for me was that I not only got called to play on that Walking In Space album, but I wrote two of the arrangements for it,” James recalled. “That was like an audition as an arranger, as well as a player, for Creed Taylor. And by that time, Quincy’s reputation was high enough that having the badge that he liked me was a great calling card.”

James went on to record hit albums for multiple labels (including one he founded, Tappan Zee) and became a mainstream jazz superstar, regarded as the godfather of radio-friendly smooth-jazz and funky r&b. His album Touchdown (1978) included his composition “Angela,” which became the theme song to the sitcom Taxi. Among his most popular albums are Two Of A Kind, a 1982 collaboration with guitarist Earl Klugh, and Double Vision, a 1986 collaboration with saxophonist David Sanborn, as well as a string of albums the pianist recorded as a member of the all-star quartet Fourplay.

One notable product of that commercial success emerged years later, when hip-hop artists began making extensive use of samples taken from classic James recordings.

“It’s the craziest thing that’s ever happened to me in the music business, and don’t ask me to explain why,” James said. “I still don’t know after all this time.” Somebody told James about a 1988 rap record by DJ Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince called He’s The DJ, I’m The Rapper that had won a Grammy. The keyboardist learned that on one track, they had essentially played “Westchester Lady,” from the keyboardist’s 1976 album Three, and rapped over the top of it.

“This came as a complete shock to me,” James said. “I had no idea how they could do this. They had not licensed it. So, that was my first awareness that I was going to have to be a policeman and I was going to have to figure out what to do about it if I was going to protect my copyright. And I did. I ended up with a very nice settlement. I got off to a pretty good start realizing that there might be some potential cottage-industry income. But I still thought it was just a fluke, and it was somewhat after that when, one after another, more requests started to come in.”

To this day, James still get requests to license samples of his work, primarily for two recordings: “Nautilus,” from 1974’s One, his CTI leader debut, and an arrangement of “Take Me To The Mardi Gras,” from his 1975 CTI release, Two.

“I’m very lucky that almost all of the records that have been sampled by other artists come from my recordings in the 1970s, and I own them,” he said. “And if it’s one of my original songs, I own the publishing of that, too. In the case of ‘Take Me To The Mardi Gras,’ it’s a Paul Simon song, so people have to go through the publisher for the song rights. But ‘Westchester Lady’ and ‘Nautilus,’ I own those.

“I try to deal with it on a case-by-case basis. Some of the things that I’ve ended up being compensated for the most were samples that I would have considered minute and almost unrecognizable to me. But every one of them is different. Usually, it’s a gray area where you think, What is it that’s making the record a hit? Is it your sample, or is it the rap, or whatever? It’s impossible to know the answer to that.”

Another mystery that often befuddles James is determining what it is exactly about his ’70s catalog that has appealed so much to multiple generations of hip-hop artists.

“I ask myself that all the time,” James said. “I’ve had a lot of conversations with rap and hip-hop artists, and I come away most of the time feeling really good that they consider my stuff having that stamp of magic. Most of the time, it’s something in the rhythm. But the whole genre is so different from the way I would have thought about creativity; those ‘chunks of sound’ are thought of by them in a completely different way.

“‘Nautilus’ is maybe the one that I can understand the best, because during the time we were recording that in the studio, [drummer] Idris Muhammad and [bassist] Gary King created magic for me. It was the magic groove that they played, and it’s a feeling that a rap artist can’t get with a computer and a drum machine. There’s a looseness and a realness that you can’t quite put your finger on—but that’s the whole reason why it’s wonderful. What’s most amazing to me is that ‘Nautilus’ has been sampled over 1,000 times, but it was the last cut on the record, and neither Creed Taylor nor I had any feeling whatsoever that it had any commercial potential. And no one paid attention to it. It wasn’t until years later when, for whatever crazy reason, that magic groove that Idris and Gary and I were playing—they found it. So ... you never really know. Enjoy making the music, and hopefully someone will hear it.” DB

This story originally was published in the October 2020 issue of DownBeat. Subscribe here.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…