Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Recently unearthed trio recordings of Bob James from 1965 find the keyboardist and composer working in a surprising mode.

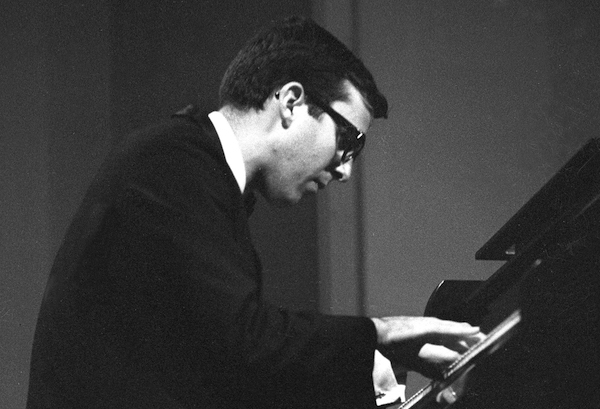

(Photo: Tom Copi)Ever since his first forays into improvisation in the late 1950s and early ’60s, Bob James has considered the piano trio to be the ultimate vehicle for playing jazz.

Now 80 years old and famous the world over for his frequently sampled jazz/pop/funk crossover tunes, the Grammy-winning keyboardist, composer and arranger has been reveling in memories of his early trio work.

Speaking to DownBeat from his home in Traverse City, Michigan, James described the excitement he’s feeling about recently unearthed recordings from two pristine 1965 trio sessions captured by George Klabin, founder and co-president of Resonance Records, who at the time was a freshman at Columbia University.

“It was such a shock to me that those recordings even existed,” said James, who was then living in New York and had recently begun leading vocalist Sarah Vaughan’s backing band. “They had never been released. So, you can image something like this suddenly coming to the surface and realizing that not only does it exist, but it’s in perfect condition—the sound is great. When I finally had the opportunity to listen to it, the memories came flooding back to me about how we made those musical choices and where it all fit in the historical timeline.”

In addition to his straightahead bebop chops, James’ playing in the early to mid-’60s drew heavily from the avant-garde classical music scene of the day. Bold new experiments in compositional form and improvisation played a major role in his development at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where James gained an abundance of experience as a collaborator and daring conceptualist while earning his bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Once Upon A Time: The Lost 1965 New York Studio Sessions (Resonance) documents a 25-year-old James fronting two acoustic trios in Columbia University’s Wollman Auditorium. It was released as an exclusive, limited-edition LP for the Aug. 29 Record Store Day retail event, with the CD and digital versions following on Sept. 4.

On the first session, recorded Jan. 20 of that year, James joins bassist Larry Rockwell, from Vaughan’s working band, and risk-taking drummer/percussionist Robert Pozar, who knew the pianist from his student days, on what could be described as a deep-dive into the avant-garde. The second session, recorded Oct. 9, is a much more straightahead affair with Detroit-bred bassist Bill Wood and drummer Omar Clay, another associate from the burgeoning Ann Arbor scene. Both sessions took place at Klabin’s invitation.

The engineer recorded James’ trios in the empty theater—which made its nine-foot Steinway concert grand available to performers—using basic, recently acquired audio equipment that included a portable, professional-quality Crown two-track recorder. His intention was to broadcast the recordings on Columbia’s radio station, WKCR-FM, where the young jazz enthusiast hosted a regular program, and to provide a copy to James, who at that time had issued only his debut, Bold Conceptions, a trio effort produced by Quincy Jones and released by Mercury in 1963.

Klabin recalled his surprise at James’ choice of material for the first session. “I started recording, and [James] starts doing this ‘out,’ avant-garde stuff,” he said. The trio played three envelope-pushing pieces—“Once Upon A Time” and “Variations,” both by James, and the Joe Zawinul composition “Lateef Minor 7th”—as well as a relatively straightahead take on “Serenata,” by Leroy Anderson and Mitchell Parrish. “I listened to it and said, ‘I’m going to put this on [the radio].’ It wasn’t what I really wanted, but I was respectful of it.

“So then I said, ‘Is it possible for you to do some other tunes that are more straightahead?’ And he said sure. Finally, toward the end of the year, he came back with a different bass player and drummer, and he did all straightahead stuff for me.” Those tracks included the Sonny Rollins bebop gem “Airegin,” the modern-jazz standard “Solar,” the ballad “Indian Summer” by Al Dubin and Victor Herbert, and an uncredited swinger titled “Long Forgotten Blues.”

The first of the two sessions proved most useful. Shortly after it was recorded, Klabin sent a copy to Bernard Stollman, founder of ESP-Disk’, the New York-based label that was then home to free-jazz pioneers Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra. Stollman agreed to record James’ free-form second album as a leader, Explosions, which was released later that year.

Klabin would go on to record several other artists at Wollman Auditorium in a similar manner to generate fresh material for his radio show. Meanwhile, he put the James tapes away, and essentially forgot about them.

It wasn’t until last year, when he encountered James during the recording sessions for reedist Eddie Daniels’ new Resonance album, Night Kisses, that Klabin got the idea to finally release the recordings that had sat in his vault for five decades. James played on the Daniels project, and in the process became reacquainted with Klabin.

“I said, ‘Bob, do you remember those recordings that we made in 1965?’ And he went, ‘What?’ So, I told him the story, and he went, ‘Really?’ I said I’d send them to him. Later, he got on the phone with me and said, ‘This is wonderful to go back and to be able to hear this.’ So, I said, ‘Would you like to put this out?’ And he said, yes.”

Apart from Bold Explorations and Explosions, Once Upon A Time is one of the few albums where listeners can hear James blatantly pushing conventional boundaries and assimilating his early-career influences from the realms of bebop and the avant-garde.

Fans eager to dig even deeper in this direction can check out the tracks where James and Pozar appear on the five-CD collection Music From The Once Festival 1961–1966 (New World Records), which documents the legendary gatherings of modernists that took place annually in Ann Arbor. James also can be heard with his band backing Eric Dolphy at the 1964 Once Festival on an extended original composition titled “A Personal Statement,” which was included as a bonus track on Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 N.Y. Studio Sessions, a Dolphy set issued by Resonance.

By the mid-1960s, Vaughan was a well- established jazz star who had been nominated for a Grammy, earned a Gold Record and performed at Carnegie Hall and the White House. As James’ association with her took shape in 1965, his playing style evolved accordingly.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…