Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Drummer and bandleader Chick Webb is barely remembered today. If he is known at all, it’s likely because he’s the man who discovered Ella Fitzgerald. But Webb’s contributions to jazz and American music go way beyond that: He was one of the most influential drummers who ever lived — having influenced everyone from Krupa and Rich to Kenny Clarke and Art Blakey — and can be credited, in good measure, as being the architect of big band drumming. As a groundbreaking player, Webb was among the first jazz drummers in history who knew about shading, dynamics, how to kick an ensemble, how to lead a band, how to back and inspire soloist and, perhaps most significantly, how to take one hell of a drum solo.

As a bandleader, Webb’s big band, which existed from about 1926 until his death in 1939 (though Fitzgerald fronted the band until around 1942) was an electrifying juggernaut that, in 1931, became the house band at The Savoy. At the Savoy, Webb’s band bested most of his competitors in famed “battle of the bands” competitions, including those led by Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington and Count Basie. The Webb/Goodman battle has become the stuff of legend. In the end, Goodman drummer Gene Krupa proclaimed, “I was never cut by a better man.” By the time of Webb’s death in 1939 at the age of 34, his band, helped in no small measure by the popularity of Fitzgerald, was one of the top bands in the nation.

The fact that he did any of this is something of a miracle. As a result of a fall he suffered as an infant, he crushed several vertebrae that required surgery. This eventually progressed to tuberculosis of the spine and a badly deformed spine, which not only stunted his growth but caused him to appear hunchbacked. That didn’t stop him from swinging, or anything else for that matter.

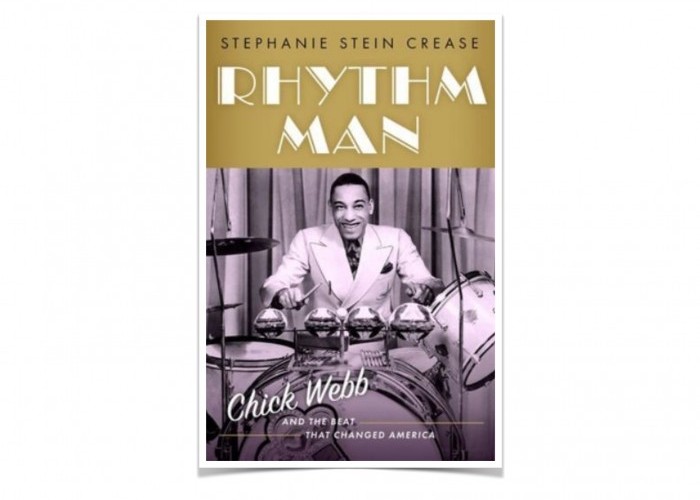

Stephanie Stein Crease, who wrote a superb biography of Gil Evans, Out of the Cool: His Life and Music, in 2002, took on the Webb project at the urging of esteemed author, critic and Oxford “Cultural Biographies” Series editor Gary Giddins. Crease’s research for the behemoth, 360-page Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America (Oxford University Press) is admirable and impressive, especially when applied to Webb’s childhood, his family, the socioeconomic climate nationally and in Webb’s native Baltimore, the entire Ella Fitzgerald saga, the rise of the big band at the Savoy, and beyond.

Crease scoured the vaults to get quotes from Webb’s musicians and those who knew Webb personally and professionally, and conducted interviews with several contemporary jazz drummers, including Kenny Washington and Bobby Sanabria. Her timeline of the band’s climb to the top, and descriptions of life on the road and various individual gigs — as well as details of the post-Webb band — paints a vivid picture of just what was going on and when. But Rhythm Man falls somewhat short, in one view, when it comes to the actual music, and the drumming of Chick Webb in particular. All the research in the world does not necessarily make for a passionate picture of one of the most swinging legends of jazz history.

As for the origins of Webb’s drumming, Crease doesn’t go much beyond saying, “He imitated the style of drummers he’s heard in parades or park bands,” she writes. “He also started practicing tricks: Rapid fire drum solos and tossing drum sticks high in the air and then catching them.” She adds that Webb learned via “copying other drummers in town, and working things out on the bandstand.” Surely, Webb had to listen to the drumming of Baby Dodds, Paul Barbarin and other early players, and research done by others through the decades indicate that he may have studied informally with Tommy Benford, who was playing with Jelly Roll Morton as early as 1928.

Further, there are several egregious errors that just don’t do a lot for the book’s credibility. Though Crease claims, “This book is the first to tell the complete story of William Henry ‘Chick’ Webb,” the fact is, drummer and historian Chet Falzerano published Chick Webb–Spinnin’ the Webb: The Little Giant, in 2014. And to write that Gene Krupa “was also from a large Jewish immigrant family and like (Benny) Goodman, was raised in the Midwest” really strains credulity. Even the layperson who watched The Gene Krupa Story knows that Krupa was born in Chicago and was a Roman Catholic who briefly studied for the priesthood. It’s hard to believe that the editors at Oxford University Press missed something like this.

Without doubt, Rhythm Man is worthwhile, and it stands as a good addition to anyone’s jazz library as a reference work, but for the most vivid, sensory experience of Chick Webb’s virtuosity, drive, intensity and unparalleled sense of swing, it’s essential that the reader listen to Webb’s Decca recording of “Clap Hands Here Comes Charlie,” or radio airchecks like “Liza” or “Harlem Congo.” And to hear the magic that Chick Webb and Ella Fitzgerald made together, check out “A Tisket A Tasket,” the number that put The First Lady on the map. Webb’s music, to this day, speaks louder than words. DB

Bruce Klauber is the biographer of Gene Krupa, co-editor of “Buddy Rich: One of a Kind” and producer of Hudson Music’s “Jazz Legends” DVD Series.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…