Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

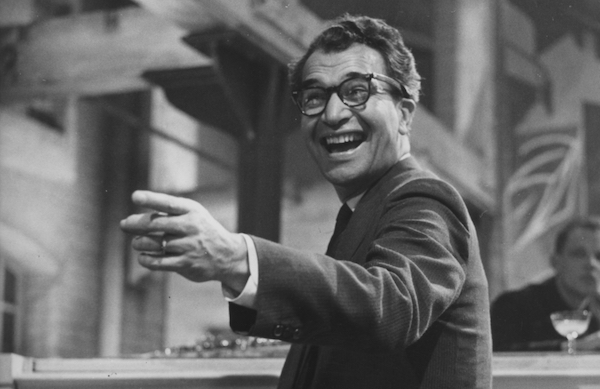

Dave Brubeck (1920–2012)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)The lesson was simple: Death is not the end, particularly when it involves a great, palpable legacy. The artistic output of the deceased might be over, but the legacy he or she leaves often lives on—relevant, yet vulnerable to cultural changes—in unpredictable ways and with a purpose that can evolve with time.

After a century of recorded history, the jazz world has become a cosmic anthology of great legacies, each with advocates to plead its case before the doorkeepers of Valhalla. Sometimes, as in the case of Bernstein, the advocacy is assumed by the family and an institutional infrastructure that is up and running. In other cases, when descendants are not there or otherwise occupied, it falls to individual scholars, researchers and biographers to do the advocacy.

The family of Dave Brubeck (1920–2012)—sons Darius, Chris, Dan and Matthew, and daughter Cathy—would like to see their father enjoy a similar kind of perpetuity, one that will last well beyond the 100th anniversary of his birth.

Indeed, Brubeck’s centennial year will be marked in many ways, including a major biography by Philip Clark, Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time (due in February from Hachette), and the new book Dave Brubeck’s Time Out by Stephen A. Crist. The latter, from Oxford University Press’ Studies in Recorded Jazz series, focuses on Brubeck’s classic 1959 album, Time Out. Even more important will be a changing of the guard overseeing the more organic parts of the pianist/composer’s heritage, as the Brubeck Institute comes to an end and the organization Brubeck Living Legacy replaces it.

No legacy can be sustained without a great career on which to stand. Brubeck’s was as epic as it was long, touching many generations. Coming in the wake of jazz’s first brushes with both popularity and modernity—swing into bebop—Brubeck was progressive both musically and socially. As early as World War II, when he created one of the early service bands, the Wolf Pack, he insisted to his commanding officer that the group be integrated. Later, he canceled a tour in the South rather than replace Eugene Wright, his African American bassist. At a time in the ’50s when jazz was in cultural retreat, Brubeck became a household word and the subject of a cover story in Time magazine. He played the first Newport Jazz Festival in 1954 and had one of history’s rare top-10 hit jazz albums with Time Out. It became a career landmark.

There are two parallel strategies for building and sustaining such a career legacy, each with its own purposes and values. One is keeping the music before to the public, a job largely controlled by record companies and market conditions. As a strategy, though, the impact of a major reissue or a previously unreleased recording can be fleeting and largely outside the control of artist estates.

The other strategy involves a more institutional investment, a direct partnership between the artist and a school that can act as both a career archive and an active agent of future evolution through music education. In 1999 and 2000, that was the path Dave and Iola Brubeck chose.

Iola was her husband’s Boswell. Seeing importance in his work early, she saved practically every concert program, review, clipping, arrangement, tax return, photograph, contract and document. In a trade where musicians typically leave a tissue-thin paper trail, Brubeck’s 70-year career is among the most exhaustively documented in jazz. Beyond that was Brubeck’s immense book of compositions, which include some of the most famous jazz standards (“The Duke,” “Blue Rondo À La Turk”), plus a diverse library of chamber and orchestral works. In the ’90s, the question was: What to do with it all? The Brubecks began exploring options—Yale, the Smithsonian, others.

Meanwhile, Don DeRosa, president of the University of the Pacific, was thinking about the future of his school’s music conservatory—and its most famous alumnus. He spotted a unique opportunity. “DeRosa had a particular vision of actively keeping Dave’s music alive,” said Chris Brubeck. “This meant not only chronicling and digitizing the archives but seeing that his music was played by student musicians as well. That sounded good. Dave didn’t want to see his legacy end up at some prestigious place buried in a million crates. But the most important thing that keeps a name alive is tying it to an education mission. You pass directly on to new players a knowledge of that legacy. That’s what makes it a living legacy. Records may reach more people, but it’s a passive relationship. What was appealing to my dad was reaching young players born in the ’80s and ’90s, so that they could carry forth some of his musical and creative values.”

The result was the Brubeck Institute, established in 2000. “It was originally an island by itself,” recalled Patrick Langham, who arrived in 2003 to oversee the first group of full-scholarship undergrad Brubeck Fellows while also running the separate UOP jazz studies program. “But they had no peer group within the music school and no dedicated faculty. I came to bridge the institute with the conservatory. There was the name Brubeck, but no one really knew what it was yet or its potential.”

The essential terms of the original accord between the university and the Brubecks transferred custody—but not ownership—of the archive to the school and established a Brubeck Jazz Festival. “It introduced the fellowship program, and it grew from there,” Langham recalled. “Outreach was a major part of it—going out and visiting other schools.” The original agreement covered 10 years, and it was renewed in 2010.

“In 20 years, the institute brought the university into a strong position in jazz education and really upped the game of the entire jazz program,” Chris Brubeck said.

In October, the university hosted its final Brubeck Jazz Festival, and the occasion brought back to the campus many former Brubeck Fellows and alumni, most now well into their own careers. “After UOP I went to The New School, then Juilliard,” said Lucas Pino, a 2005 Brubeck Fellow who leads the acclaimed No Net Nonet. “Though both were extremely positive, they pale in comparison to how formative and impactful the Brubeck Institute was.”

In the early years of the Brubeck Institute, Dave himself was deeply involved. “He would do everything,” said Simon Rowe, who headed the institute from 2011 to 2016. “He’d perform with Brubeck Fellows and do concerts. He would visit often and perform classical and jazz pieces. He was delighted to have this innovative organization celebrating his values and music.”

In March 2019, Pamela A. Eibeck, then the University of the Pacific’s president, sprang a big surprise. As of Dec. 31, she announced, UOP and the Brubeck family would not be renewing their 20-year accord. The Brubeck Institute would be dissolved, the archive would leave, and the fellowship program would be revised and renamed the Pacific Jazz Ambassadors.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…