Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

In Memoriam: Gordon Goodwin, 1954–2025

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Carmen Lundy (left), Darryl Hall and Marvin “Smitty” Smith perform at the Duc de Lombards in Paris.

(Photo: © Sarah Berrurier)The city of Paris was blessed with an abundance of great music in October and November. Jason Marsalis, who has relocated to Orléans, France, appeared on vibes at the Duc des Lombards. On the same night, the venue Sunside/Sunset presented elegant jazz pianist Enrico Pieranunzi and rough blues marvel Watermelon Slim.

One could also note the recent appearances of keyboardist/vocalist Ben Sidran (and his son Leo) at Sunside, trumpeter Marquis Hill at Duc and the ebullient New Jersey collective Spirit of Life Ensemble at the Caveau de la Huchette (a show for dancers only!).

But the greatest concerts of the bunch happened at the Duc des Lombards, where all of the following concerts took place.

On Oct. 25, pianist Spike Wilner (proprietor of the New York City venues Smalls and Mezzrow) and his quartet summoned the New York spirit and delivered two nights of swinging invention.

With the superb, crisp support of Tyler Mitchell on bass and Anthony Pinciotti on drums, the band explored ravishing tunes like “How Am I To Know?” and “Iceberg Slim,” groove numbers like “A Stitch In Time” and “Blues For The Common Man” and a slow blues based on “Parker’s Mood” that ratcheted into an obsessive 3/4 groove. Tenor saxophonist Joel Frahm was as strong as ever and delivered an unstoppable flow of ideas expressed with great poise and stamina.

Wilner’s music is based on atmospheres that keep changing, veering from poetry to swing, forcefulness to quietness. His pianism, his call-and-response phrases and overall invention are quite unique. His take on “Warm Valley” was intimate, displaying huge emotional involvement.

The same could be said of vocalist Carmen Lundy, who turned in four performances at Duc from Oct. 31–Nov. 1. Her forceful, funky lyricism is a clear departure from the excessive applications of cuteness and cliché that are so many singers’ pitfalls.

Lundy demonstrated her leadership skills, steering the music in whatever direction she wanted and gracefully guiding her young accompanists: Andrew Renfroe (guitar) and Victor Gould (piano). Renfroe added intelligent touches of color as a rhythm player and energy as a soloist. Gould was equally inspired, reaching soaring heights on “Afterglow.”

Both were fed huge doses of groove by Darryl Hall on electric and acoustic bass and Marvin “Smitty” Smith on drums. When those two lock into a groove, there’s no escaping its exhilarating power.

Lundy’s scatting is very personal, as is her delivery and tone, operatically soaring with great energy or whispering with a suggestion of repressed strength. The fervor was candidly intense on songs like “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings,” “When Will They Learn” and “Come Home,” on which she managed to bring together softness, swing and aggressive beats with fluid musicality.

Pianist/vocalist Freddy Cole, 85, has always been a stickler for melody. He is also someone with in-depth knowledge of the standards. The bluesy gravel in his voice comes as a contrast to the sentimental material he explores with narrative sensibility.

On Nov. 4–5, unobtrusively supported by a fine quartet comprising the subtle Henry Conerway III on drums, Kris Kaiser on guitar and Barry Stephenson Jr. on bass, Cole delivered miniature phrases on piano that were reminiscent of Count Basie. His flawless interpretation of “A Lovely Way To Spend the Evening”, “Comme Ci, Comme Ca” (known in French as “Clopin-Clopant”) and “Easy Living” were touching. Closing with a funky blues, Cole used the raspiness in his voice to great effect.

Veteran pianist Steve Kuhn is full of zest and sprightly invention. With a massive amount of swing, he showed how the Bill Evans legacy could be developed and rejuvenated at Duc on Nov. 7–8.

One could feel the weight of maturity in the way Kuhn approached standards, even well-traveled tunes like “Blue Bossa,” a nod to trumpeter Kenny Dorham, who was among Kuhn’s first employers in 1959.

With his melodic developments and quirky rhythmic phrases, he let his lyrical playfulness and his drive shine, jumping from one idea to the next with great aplomb and precision.

“Emily” and “I Waited For You” were sensitive, as were his takes on “Slow Hot Wind” and his melodic rubato on “Trance/Oceans In The Sky.”

The support of bassist David Wong and drummer Billy Drummond was strong, each bringing a palpable presence without ever becoming overwhelming. The interaction between them really gelled into a textured unity.

Goodwin was one of the most acclaimed, successful and influential jazz musicians of his generation.

Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Nov 13, 2025 10:00 AM

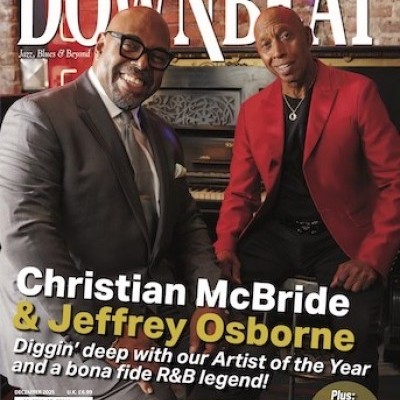

For results of DownBeat’s 90th Annual Readers Poll, complete with feature articles from our December 2025 issue,…

Flea has returned to his first instrument — the trumpet — and assembled a dream band of jazz musicians to record a new album.

Dec 2, 2025 2:01 AM

After a nearly five-decade career as one of his generation’s defining rock bassists, Flea has returned to his first…

“It’s a pleasure and an honor to interpret the music of Oscar Peterson in his native city,” said Jim Doxas in regard to celebrating the Canadian legend. “He traveled the world, but never forgot Montreal.”

Nov 18, 2025 12:16 PM

In the pantheon of jazz luminaries, few shine as brightly, or swing as hard, as Oscar Peterson. A century ago, a…

Dec 11, 2025 11:00 AM

DownBeat presents a complete list of the 4-, 4½- and 5-star albums from 2025 in one convenient package. It’s a great…