Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“Getting into jazz changed everything for me,” Wamble said.

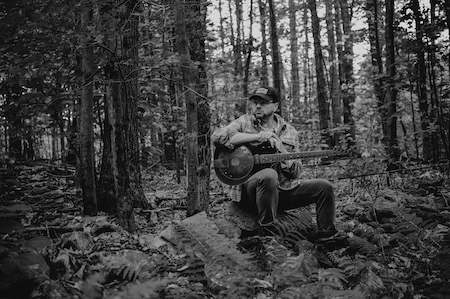

(Photo: Jenny Anderson)Beyond is a good descriptor for Doug Wamble’s compelling October release, Blues In The Present Tense, on which the 50-year-old singer/songwriter/guitarist — releasing his first album since 2013’s Rednecktellectual, an overdubbed solo recital — artfully mixes multiple genres.

The title track convincingly imagines the subconscious mindset underlying the previous U.S. president’s cynical grift, and songs like “MAGA Brain,” “No Worries” and “If I’m Evil” portray psychological archetypes that fuel 21st century dystopia, depicting the cloistered, tribal worldview of Wamble’s family, neighbors and friends in his hometown of Memphis. Other blues emanate from the inclusive, ecumenical consciousness that has animated Wamble’s three decades as a professional musician. The lyrics — some demotic, some anthemic — have an artfully vernacular quality. He sings in a pellucid, conversational tenor, phrasing like a horn, self-accompanying on a thick-stringed Resophonic guitar with “an old sound that can give me everything from Delta blues to a Grant Green-Kenny Burrell tone.”

For the recording, Wamble convened a dream band. Branford Marsalis (under the sobriquet Prometheus Jenkins), Eric Revis and Jeff “Tain” Watts reunite on record for the first time in a decade, admirably fulfilling the function, swinging relentlessly.

The project gestated through Wamble’s relationship with Revis, a friend since the guitarist’s band opened for the Branford Marsalis Quartet on several concerts a few decades back. “We love a lot of music in common, from Chris Whitley to Son House to Prince to Dewey Redman,” said Wamble, who brought Revis on a 2012 Jazz at Lincoln Center concert that’s digitally available on his Bandcamp site as The Traveler–Live In New York City. He spoke via Zoom in early September from his studio in the Bronx.

“We’ve always tried to do something together, which is difficult because Eric hasn’t lived in New York in a long time and our schedules are always crazy. But I kept it in the back of my mind. I wrote a lot of this music in the year or so before COVID, when everything that shifted the ground underneath us in 2020 was already happening. As I got deeper into the writing, I found myself facing this strange turn of events I’ve seen in my lifetime. I grew up in a very conservative, churchgoing family. We’re close. I’ve been politically at odds with a lot of them for a long time, but never with the fervor of these last few years. It’s become more and more difficult to agree to disagree. My daughter is transgender, so we can’t agree to disagree that she has a right to live her life. And I can’t agree to disagree that racism isn’t a problem in America. It’s fundamental to my whole belief system that we must confront these things and talk about them honestly. When we don’t, it drives us further and further apart. That’s where my head was at when I was writing all these tunes. And as I wrote them, the notion of what this could be if I put them all together took shape.”

The COVID-19 lockdown forestalled a planned March recording date. After the 2020 election, Wamble thought “it would no longer be relevant to put out this music.”

Then, the Jan. 6 riot happened at the Capitol in Washington D.C.

“It doesn’t really matter who’s president — the problems are just going to be there,” Wamble said. So he decided to persevere. He booked a date that suited the respective itineraries of Revis, Watts and a blues-and-roots oriented tenor saxophonist who canceled on short notice. Wamble called Marsalis, whose schedule fortuitously situated him in New York.

“I knew we’d have one day to make this record,” Wamble said. “I think it took four hours. We didn’t rehearse. We just went in and played. We didn’t listen back to anything. The simple forms let you internalize the feeling of the tune. I used to write complicated music with crazy time shifts and chord progressions — and that’s cool. But now I tend to like things where the form feels comforting and inviting, and allows the creativity of the moment to speak louder than if everyone’s trying to count: ‘Here comes that bar of 13 I’ve got to nail.’”

“Everybody liked the tunes, which placed us all in service of the music, of conveying the song, rather than session mode,” Revis said. “Plus, me, Branford and Tain hadn’t played collectively in a while. It was very relaxed. When Doug sent me the demos, I realized the songs are an amalgam of his whole thing. He’s expressing ideas that are relevant today in a blues singer-songwriter context; the songs all feel familiar, not like you’ve heard it before, but because of his deep roots, it’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, I know this.’ Then there’s a sophisticated twist that makes you go, ‘Wow.’”

“The sound of the blues is incredibly adaptable, and Doug has a really good relationship with the sound of the blues, not just blues as a harmonic construct,” said Marsalis, who blows up a storm on tenor and soprano throughout the proceedings.

Blues In The Present Tense is the first Wamble-Marsalis encounter since the early 2000s, when Marsalis produced two Wamble dates on Marsalis Music. On Country Libation, Wamble’s 2003 debut album, Marsalis played soprano saxophone on a well-wrought cover of Sting’s “Walking On The Moon”; on the 2005 followup, Bluestate, he uncorked a rollicking tenor declamation on Mahalia Jackson’s “Rockin’ Jerusalem.”

Although they’d intersected several times during the ’90s, they first conversed seriously at the end of the decade, when Jason Marsalis brought Wamble to Branford’s house. Wamble had recently performed on Wynton Marsalis’ epic Big Train, the first of six albums he’s done with Wynton, and then an opportunity to sign with a major label fell through.

“I was asking Branford’s advice on recording and other things,” Wamble said. “And he said, ‘Why don’t you send me some of your music? If you suck, I’ll tell you.’” He sent Marsalis a demo of complex, Wynton-inspired octet music he’d done for Blue Note, and live recordings of shows, both as a leader and with Steven Bernstein’s Millennial Territory Orchestra. “A few months after 9/11, Branford emailed me, ‘I’m starting a label. Let’s do a record.’”

“I liked the way he sounded,” Marsalis said. “The phrasing tends to be strange on instruments where you don’t have to breathe. But Doug was playing this electrified acoustic instrument, so I liked it already, and he breathes when he plays. He doesn’t use effects. It doesn’t sound like he’s playing well-rehearsed licks that he repeats over and over. So I was a fan.

“Ultimately, Doug likes the sound of jazz. We didn’t talk about killing solos. We talked about killing tunes — great sounds, great bands. That was refreshing.”

“Getting into jazz changed everything for me,” Wamble said. “It set me on the path I’m on today. Not least — and very related to this album — it made me confront my history of racism. I think we should be open about who we used to be and how we’ve changed. I used to say and do racist things, and I was homophobic — a lot of things I’m not proud of.”

Will the release of Blues In The Present Tense provoke Wamble to undertake more creative projects in the foreseeable future?

“I wrote a bunch of songs in my 20s with verses — very much in the style of American popular song,” he said. “I’d like to record some of those. I want to make the jazz side of my life more present than it has been because I’ve missed it. I enjoy playing that stuff.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…