Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

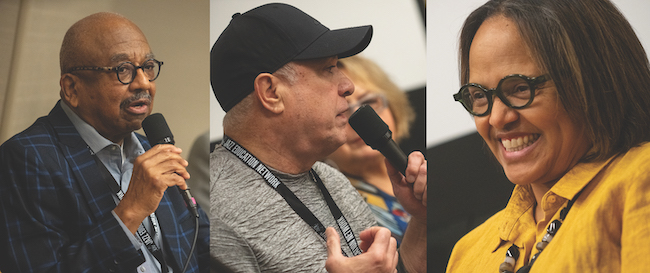

Duane Davis (left), Oscar Hernandez and Terri Lyne Carrington at this year’s JEN Conference in New Orleans.

(Photo: Frances Scanlon)There are times when you listen to jazz musicians reveal the stories behind their lives and careers, and you can’t help but drop your jaw and say, “Wow.”

Such was the case during a panel discussion at the Jazz Education Network Conference in New Orleans this past January. When JEN co-founder Mary Jo Papich moderated a panel of LeJENds of Jazz (artists and educators who received the organization’s top honors this year), an awe-inspiring world of humble beginnings, God-given talent and unlocked potential came into view.

Terri Lyne Carrington, the drummer, composer, educator and change agent who received this year’s LeJENd of Jazz Education Award, has been leading a charge for inclusivity in jazz that has dramatically changed the way we think about who should be on the bandstand. As the founder and artistic director of the Berklee College of Music Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, Carrington said that schools of music need to look beyond the norms sometimes to find students with special voices that just need to be developed. But as a champion of women and non-binary musicians in jazz, she also wants to be careful not to put them in a box.

“I think it’s good to start thinking about, because it’s easy to silo women,” Carrington said about women-specific jazz awards and programs. “[Terms like] ‘sisters in jazz’ or ‘women in jazz’ put them in a box sometimes. What is needed in the music is more gender equity, and not like women over here or women over there. … That’s the cultural transformation: gender equity.”

“The perspective that Terri Lyne shared is priceless,” said Oscar Hernandez, leader of the Spanish Harlem Orchestra and recipient of the LeJENd of Latin Jazz award. “Because it’s thinking outside the box, in terms of impacting people’s lives that would normally not be impacted, on some level.

“I’m originally from the South Bronx. We were a very poor family of 11. And I say — kind of figuratively, but in a sense literally — music saved my life.

“There were dynamics that were happening, especially the cultural revolution of Latinos in the ’60s, stemming from the ’40s and ’50s and the music of Tito Puente, Machito and Tito Rodriguez — the big three — which, from my perspective, is the equivalent of Duke Ellington and Count Basie on its own level.”

Hernandez could have been just another overlooked kid, but he found music, and mentors, and somehow made his way to leading one of the world’s most renowned Latin jazz bands.

“I feel that there’s a spiritual, divine intervention that I can’t explain,” he said. “Even the fact that I play piano, I can’t even explain it. Because we certainly couldn’t afford to buy a piano when when I was a kid. That was kind of out of the realm of reality.”

The messages delivered by Carrington and Hernandez resonated with vocalist and educator Duane Davis, recipient of the Ellis Marsalis Jr. Jazz Educator of the Year award.

“I had so many people who didn’t believe in me, that I had the potential to be a musician,” Davis said. “So, when I finished high school, I just worked on the railroad with my father, making more money than he did, because I had typing skills and shorthand skills. I was the first African American hired in the clerical department.

“But during that year, my high school music teacher said, ‘You should be in college. You should be in music.’ I was always in music, but we didn’t have a piano, like Oscar said of his family, and everything I learned, I learned by ear. But she could see deeper in me; she saw possibilities.

“When she saw that, I was so thankful, because I can remember [many years later] sitting in a faculty meeting at the community college, and they were rejecting some students. And tears came to my eyes and I said, ‘You cannot reject that student. I was that student. There are possibilities there. We have to find what’s going to unlock that kid.’”

That’s what jazz is all about. Finding the key. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…