Jun 17, 2025 11:12 AM

Kandace Springs Sings Billie Holiday

When it came time to pose for the cover of her new album, Lady In Satin — a tribute to Billie Holiday’s 1958…

NEA Jazz Masters David Baker (left), George Avakian, Candido Camero and Joe Wilder pose for a portrait at the 2010 NEA Jazz Masters Awards Ceremony & Concert.

(Photo: Tom Pich, courtesy of National Endowment for the Arts)George Avakian, the Grammy-winning jazz producer and NEA Jazz Master who worked with some of the genre’s most important artists and brought numerous innovations to the music industry, died Nov. 22 in Manhattan. He was 98.

In honor of his passing, we present John McDonough’s profile of Avakian that ran in DownBeat’s October 2000 issue, when Avakian received the magazine’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

George Avakian: Record Innovator

In recognizing George Avakian as recipient of the DownBeat Lifetime Achievement Award—counterpart to the Hall of Fame created in 1981 to recognize the contributions and influences of those without whom the history of jazz would likely be diminished or perhaps even nonexistent—the award comes full circle. The first recipient was John Hammond, the legendary talent guru and producer at Columbia Records who not only set an extremely high bar of achievement for all future recipients, but also served as a kind of mentor to Avakian in his early work for Columbia in 1940.

The innovations Avakian brought or helped bring to the recording industry are so fundamental and taken for granted today that most people under the age of 70 would find it hard to imagine there was ever a time when they didn’t exist. At least five are pre-eminent.

One: He was producer of the first jazz album in the history of the industry, meaning a series of sessions recorded with the specific intent of issuing them together and not as singles. The album, Chicago Jazz (Decca 121), reunited Eddie Condon, Pee Wee Russell and others from the late-’20s Chicago scene and was released in March 1940. Other sets celebrating New Orleans and New York followed.

Two: He organized and launched the “Hot Jazz Classics” line for Columbia, the industry’s first regular series of reissue albums accompanied by notations explaining the history and importance of the material. The series began in 1940, took a wartime hiatus, then continued up to the introduction of the LP.

Three: He helped to establish the long-playing record as the most important single innovation of the record industry during the 20th century and Columbia as the dominant label in its first decade. He planned the first 100 10-inch pop LPs released in the wake of the microgroove introduction in June 1948. He was also a key figure in the breakthrough of the 12-inch LP from a primarily classical medium (“Masterworks”) to a popular record (the Columbia GL, or “gray label,” 500 series).

Four: Under Avakian’s lead, Columbia became the first major label to enter the field of live pop and jazz recording, at a time when only smaller specialty labels such as Norman Granz’s Clef were doing it. Inspired by the success of the Benny Goodman Carnegie Hall concert and broadcast LPs, Avakian recorded Harry James, Lionel Hampton and others in ballroom settings and Louis Armstrong on tour in Europe in 1955, all of which led to the precedent-shattering series of four albums covering the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival.

Five: He revitalized the careers of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington by taking what they could do best and wrapping it in the synergism of the concept album (Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy, Ellington At Newport).

Avakian was born in 1919 in Armavir, Russia, to Armenian parents. He attended Yale University, where in 1937–’38 he came to meet the early jazz scholar/collector and DownBeat columnist Marshall Stearns, who was then working on his Ph.D. in English literature. In those days the records of the early masters of jazz were for practical purposes out of print and unobtainable, except for a trickle of single 78s that began to appear in 1935–’36. Bix Beiderbecke and Bessie Smith each had been the focus of a “memorial album,” but the concept of regular album-length reissues had yet to be invented. Mostly the music survived in the hands of a few pioneering collectors, one of whom was Stearns. His closet contained one of the most complete jazz collections in America. (It later became the cornerstone of the collection at the Institute for Jazz Studies at Rutgers University.)

Avakian immediately became part of a small group that would come to his apartment every Friday and listen to early records by Armstrong, Ellington, Smith, Beiderbecke, the “Chicagoans” and more. Avakian formed his mature tastes here, and the experience would quickly bring him to record Chicago Jazz, a packet of six 78-rpm records for Decca, and soon after, launch the “Hot Jazz Classics” albums at Columbia, all done while still at Yale.

“When I saw how much alcohol Eddie Condon and his guys drank and abused their health,” Avakian said, “I was very alarmed and became convinced they couldn’t possibly live much longer. So I persuaded Jack Kapp at Decca to let me produce a series of reunions to document this music before it was too late. They were only in their mid-30s. But I was 20. What did I know about drinking?”

When Life magazine ran a major article in August 1938 about the history and roots of swing, Ted Wallerstein, soon to become the first president of Columbia Records under its new parent CBS, had an idea: Why not reissue some of the records referred to in the Life story? Wallerstein moved to Columbia in late 1938, and he asked Hammond to undertake the job. Hammond was too busy, but recommended Avakian. A meeting was arranged in February 1940 in which Wallerstein outlined his idea and asked Avakian to research the masters and assemble a series of 78-rpm albums for $25 a week in pay. Thus, the 20-year-old Avakian became the first “authoritative” person to review the short history of jazz up to 1940 and nominate a fundamental canon of indispensable classics that could be heard by a wide audience. His selections included the Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens, the now familiar Beiderbecke and Smith classics, and basic Fletcher Henderson and Ellington collections. In the process, he also became the first producer to discover and issue unreleased alternate takes. His choices would prove immutable, as they would influence the basic writing about jazz at a critical time when the music was beginning to be seriously written about.

In 1951, Avakian expanded these albums to the LP format to create the famous four-volume Louis Armstrong Story and other LPs. Once in general circulation, they would remain in print until the advent of the CD and have immense impact for generations to come as new listeners came to jazz.

After the war, in 1946, Avakian accepted Wallerstein’s invitation to join the Columbia production staff. He would remain there until early 1958, during which time he achieved the milestones that continue to define his career—the Armstrong Plays Handy/Fats Waller sessions, Ellington At Newport in 1956, the Dave Brubeck quartet sessions with Paul Desmond, LPs by Buck Clayton, Eddie Condon, J.J. Johnson & Kai Winding, Erroll Garner, Mahalia Jackson, neo-trad projects by Wally Rose and Turk Murphy, and even the first Roswell Rudd with Eli’s Chosen Six.

And, of course, he signed Miles Davis, which also brought John Coltrane to Columbia in his prime. Davis’ working habits and bands had been inconsistent. If Columbia was to invest in Davis, he could not drift artistically or professionally. Davis observed how Avakian and Columbia had taken the Brubeck quartet from a relatively small career scale and launched it to international fame, and was eager to associate with Columbia. He frequently approached Avakian, who found reasons to politely delay a decision until he felt Davis was ready to move to the next level.

“He was under contract to Bob Weinstock at Prestige,” Avakian said. “Then one day in 1954 or ’55 Miles came up with an interesting idea. He said he could start recording for Columbia now, but that we would hold the masters until the Prestige contract ended in February 1957. Columbia would help arrange the kind of bookings that could support a stable group, then begin a publicity buildup about six months before the switch. The quintet’s first Columbia session was in October 1955. I consulted from the beginning with Weinstock, who was a realist all the way and totally cooperative. He understood that Miles was ready to move to Columbia. He also realized that he could profit not only by recording Miles in a consistent setting for the balance of the Prestige contract, but by talking advantage of Columbia’s publicity effort for the last six of seven months.”

In the summer of 1955, Avakian issued the first and perhaps the best LP sampler ever, I Like Jazz, a capsule jazz history, intelligently annotated, that sold for only $1 and served as a powerful marketing tool showcasing the Columbia catalog. As chief of Columbia’s pop album and international divisions and through a combination of influential reissues and new sessions, he made Columbia the most powerful force in jazz among the majors.

By the fall of 1957, however, he left Columbia. “I had to get out of the headlong non-stop direction I was in,” he said. Avakian chose to accept the invitation of his friend Richard Bock and become partner in Bock’s Pacific Jazz Records, soon to called World Pacific Records.

In 1959 he moved to Warner Bros., where two of his closest former Columbia colleagues, Jim Conkling and Hal Cook, were laying the foundations that would make the label a power in the industry. Conkling, president of Columbia during Avakian’s prime years there, had been offered a two-year contract to start a record label for the company. He brought with him Cook, who had built the first company-owned distribution system in the industry while at Columbia. Avakian joined Warner Bros. with a mandate to build a strong pop catalog for the new label, an assignment that cut his activity in jazz to virtually nothing, although he did manage to sign drummer Chico Hamilton. Conkling had looked to the Warner film division for potential pop talent, a strategy that led him to record actor Tab Hunter. Even before Avakian moved to WB, Conkling had asked him to produce Hunter’s initial Warner single, “Jealous Heart,” which became the label’s first charted single.

“The idea was to build an across-the-board album company,” Avakian recalls. Avakian signed the Everly Brothers out of Nashville and a Chicago accountant with a knack for comedy named Bob Newhart.

When Conkling’s contract was up in 1962, Avakian was offered the presidency of WB Records. But a desire to remain close to production and as far away from Los Angeles as possible led him to accept a position at RCA Victor, where he was brought in to improve the company’s sagging pop album sales.

“There’s nothing quite like it,” Springs says of working with an orchestra. “It’s 60 people working in harmony in the moment. Singing with them is kind of empowering but also humbling at the same time.”

Jun 17, 2025 11:12 AM

When it came time to pose for the cover of her new album, Lady In Satin — a tribute to Billie Holiday’s 1958…

James Brandon Lewis earned honors for Artist of the Year and Tenor Saxophonist of the Year. Three of his recordings placed in the Albums of the Year category.

Jul 17, 2025 12:44 PM

You see before you what we believe is the largest and most comprehensive Critics Poll in the history of jazz. DownBeat…

Galper was often regarded as an underrated master of his craft.

Jul 22, 2025 10:58 AM

Hal Galper, a pianist, composer and arranger who enjoyed a substantial performing career but made perhaps a deeper…

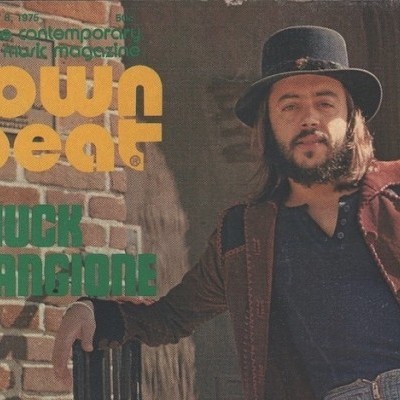

Chuck Mangione on the cover of the May 8, 1975, edition of DownBeat.

Jul 29, 2025 1:00 PM

Chuck Mangione, one of the most popular trumpeters in jazz history, passed away on July 24 at home in Rochester, New…

“Hamiet was one of the most underrated musicians ever,” says Whitaker of baritone saxophonist Hamiet Bluiett.

Jul 8, 2025 7:30 AM

At 56, Rodney Whitaker, professor of jazz bass and director of jazz studies at Michigan State University, is equally…