Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

There’s something admirable about the Jimi Hendrix estate’s willingness to put their name on Live In Maui, a warts-and-all document.

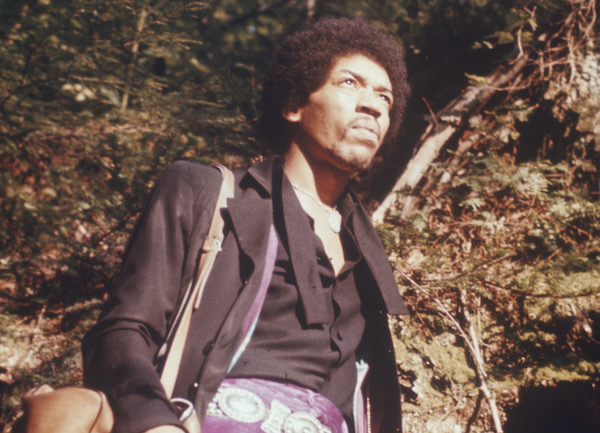

(Photo: Courtesy Experience Hendrix)As fascinating as it is to hear Live In Maui (Experience Hendrix/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Entertainment 19439799042; 51:34/48:45 ****), a thrilling document of a July 1970 Jimi Hendrix Experience performance for a few dozen fans in a pasture situated near the Haleakala Crater, the story of how this show came to pass is perhaps even more captivating.

Hendrix, drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Billy Cox had a Honolulu stadium gig and some much-needed downtime in Hawaii on their schedule. But instead of relaxing, the trio were coaxed by manager Michael Jeffrey into taking part in Rainbow Bridge—a cockamamie, independent art film—and playing a hastily assembled gig as part of what was dubbed a “vibratory color/sound experiment.”

What maybe helped convince the band to brave 30 m.p.h. winds and a gaggle of people grouped together by their astrological signs was that Jeffrey got Reprise Records to fund the construction of Hendrix’s Electric Lady Studios. Or maybe—according to interviews with Chuck Wein, the film’s director, on the DVD accompanying this multidisc set—the guitarist was on board with connecting the “enlightened and unenlightened” via that “rainbow bridge.”

Whatever the case, Hendrix and the Experience gave their all at this unusual gig, which stretched over two sets—one that stuck to familiar tunes like “Foxey Lady” and “Purple Haze,” and another that highlighted material the group recorded for what would have been its fourth studio album. Footage from the performance wound up in the finished film—which also featured a wonderfully grouchy cameo from Hendrix—but, strangely, the 1971 soundtrack was made up entirely of unused studio material.

There’s a notable looseness to the first set that only becomes more pronounced as it moves through its 10 tracks. Mitchell’s playing gets especially ragged, with awkward fills and his struggling to find the downbeat on “Lover Man.” The drummer’s work wasn’t helped by technical issues with the original multitrack recordings and the raging winds that affected several songs. (Mitchell later would rerecord the drum parts for several songs that feature in the performances here.)

By the second set, a measure of stiffness creeps into the group’s playing, underlining how new some of these songs were to the trio. The Experience is still comfortable enough turning “Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)” and “Midnight Lightning” into a medley on the fly, but the punch and swing of funk-infused rockers like “Dolly Dagger” is tempered. The trio also occasionally loses sight of the finish line, as an otherwise wonderful take of “Straight Ahead” seems to crumble toward the end.

There’s definitely something admirable about the Hendrix estate’s willingness to put their name on this warts-and-all document. That decision was made a lot easier thanks to Hendrix’s stellar work here. Even at its shaggiest, his playing is never anything less than electrifying. He especially excels on the slow blues numbers: His solo on “Hear My Train A-Comin’” starts off humbly before he unfurls a furious squall of notes and fuzzed-out chords; and the band’s churning version of “Red House” is filled with the guitarist’s quick melodic curlicues and playful energy.

Whether Hendrix was onstage that afternoon as a favor to his manager or to be part of this proto-New Age experiment can’t ever be made clear—even with the filmed concert footage. What does come across as loudly as the music is just how much he loved playing with Mitchell and Cox, and how much Hendrix enjoyed performing for an audience. When he’s not completely lost in the music or plucking out a solo using his teeth, he looks entirely joyful.

Hendrix’s death less than three months later might cast some small shadow on the ebullience displayed here, but don’t let it linger. Put these discs on repeat and soak in every moment like an afternoon in the Hawaiian sun. DB

This story originally was published in the February 2021 issue of DownBeat. Subscribe here.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…