Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“The way I keep myself being original is by not listening to other recorded music,” Pascoal says.

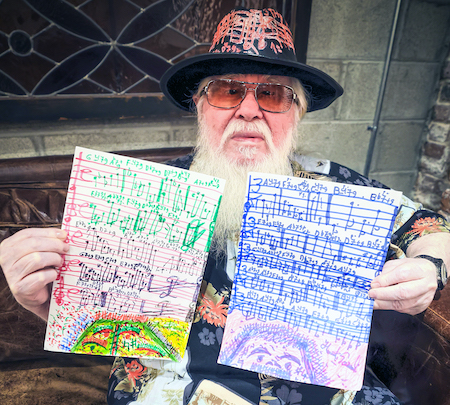

(Photo: Michael Jackson)Hermeto Pascoal, the Brazilian-born multi-instrumentalist/composer/orchestrator, is one of the world’s most prolific creative forces. If you check the 86-year-old’s more recent releases, such as the diverse No Mundo dos Sons (Selo Sesc, 2017), the Grammy-winning big band album Natureza Universal (Scubidu Music, 2017) or his wildly folkloric 2019 Latin Grammy-winner E sua visão original do forró (Scubidu Music, rec’d 1999), which revisits the formative accordion-led forró dance music he grew up with, there’s little evidence of any slowdown in his output. Yet Pascoal, despite his communicative, man-of-the-people mission, is a musician’s musician, not so well known, perhaps, amongst the plebiscite.

This writer first encountered his name via trumpeter Dave Defries’ composition “Hermeto’s Giant Breakfast,” performed by the U.K.’s Loose Tubes in the ’80s. As for “o Bruxo” (“the sorcerer” or “cosmic emissary,” as the Brazilian wizard is known), his oeuvre is hard to quantify. He’s ceaselessly composing, often writing charts on uncommon or temporary surfaces such as walls, hats or takeaway food containers, deploying conventional five-line staff (all chords annotated) with a thick, colored marker that helps him to visualize up close, since he is legally blind.

Though he and his dedicated sextet of virtuosi — including son Fabio on percussion; legendary bassist Itibere Zwarg and his son, drummer Ajurinã; fiery pianist André Marques; and rugged saxophonist/flutist/piccolo player Jota Pê — travel widely, prior to the group’s appearance at Chicago’s Thalia Hall this May, it had been almost 20 years since Pascoal played the Windy City.

The almost two-hour concert was intense and relentless, including thrilling segments when an already ambitious theme would double, sometimes triple, in tempo. Songs included “Maracatu,” “Papagaio,” “Republico,” “Ailin” and the well known “Forró Brasil.” The set featured few moments of respite and, due to a sore throat that kept him from singing, Pascoal declined to play his tea kettle with trumpet mouthpiece, which lay alongside his melodica and berrante, or bull’s horn, at the ready. Before an encore of “Irmaos Latinos,” the set capped with the 7/4 samba vamp “Jegue” (for evidence of Pascoal’s brawny tenor saxophone of yore, check the 2022 reissue of a 1981 live date on Far Out Recordings, which climaxes with “Jegue”).

The following interview took place via Zoom a week after the Chicago performance.

Michael Jackson: Why did it take so long for you to return to Chicago? You were last here almost two decades ago.

Hermeto Pascoal (via manager/translator Flavio de Abreu): I would blame it on commercial music, (which has) a lot of money invested (for touring), whereas with our music we have to pay for expenses and insurance, we are basically self-funded. My music is universal and we’re very lucky because it goes everywhere, flows like the water and the wind, and that’s why I’m also here, despite the difficulties.

Jackson: Going all the way back to your trio with Airto Moreira and Humberto Clayber in the mid-’60s, there are some Chicago musicians that are recalled — Lennie Tristano and Ramsey Lewis — yet your piano playing is more exciting than both of them. And, to boot, you play great flute. Do you remember that session? I hear whiffs of Jobim, who you worked with, during “Clerenice,” and Humberto Clayber’s “João Sem Braço” reminds me of Ray Bryant’s “Cubano Chant.” What were your influences in those early days of Sambrasa Trio?

Pascoal: I’m going to tell an anecdote that happened right before Tom Jobim passed away. In an elevator, we had time to chat as we went from the first to the sixth floor, and Jobim’s music was playing in the elevator. He took his hat off and said, “I would like to play more music like you do, more free with mixed genres. How can I do it?” And I said. “Look, you are so well respected in the U.S. [he was living in the U.S. at the time], what you have to do is learn from them, get the influences from the U.S. and then go back home and be around Brazilian musicians, play with them and then you will be freer.” That’s what I did and that’s my advice regarding these musical exchanges. And now, spiritually, Tom Jobim is telling me, “I dated more than I played!”

Jackson: That’s what Jobim said at the time?

Pascoal: Right now, Tom Jobim’s spirit just told me that. “He dated more than he played.” I am sensitive; I’m a medium you know?

Jackson: Latin musicians often have this extra level of energy or fire. What provides that extra spark?

Pascoal: When I came to the U.S. in 1967, I noticed jazz musicians were basically fighting each other on stage, disputing who was best, who was the fastest. Jazz was an argument you had to win; sometimes I felt that they were so focused on winning the battle instead of considering the music onstage something collective about freedom for creation. I noticed something absurd, that the improvisation solos were written and studied, and that goes against the concept of improvisation, because it has to flow. A few musicians were not like that: Miles Davis, Thad Jones, Cannonball Adderley, my friend Ron Carter. After a few of them passed away, jazz started this mentality of being the fastest, being technically better than the others, instead of really playing together and enjoying the moment.

Jackson: Though you have recorded more than 30 albums under your own name, including some classics, you’re still often name-checked for having recorded with Miles Davis on Live-Evil in 1970. Though Davis acknowledged your genius, you weren’t credited for your compositions on the original release. Were you aware of this at the time, and do such matters concern you, since you are constantly composing new material?

Pascoal: The most important thing for me is the meeting with Miles Davis on Earth. The fact our two souls met on this level is beyond anything else in terms of money, credits or whatever. Being such a great musician and an elevated soul, Miles would never steal anything from me. It was probably a misunderstanding with management or whatever. I don’t think that Miles stole from me at all. I was asked back in the day and people wanted to make sensationalism over that fact. My take is the experience that we lived together and that Miles left amazing work, beautiful music. Even though we played together, and I listened to him live, however, I don’t listen to Miles or any other recorded music, even my own music, because I don’t want to imitate anything. The way I keep myself being original is by not listening to other recorded music.

Jackson: On Live-Evil it seems you helped push Miles in a feral, more primitive direction, turned his art in the direction of late-period Picasso, or a Jean-Michel Basquiat. You hear Live-Evil and Miles is playing out of his skin with sounds that are less jazz and more from nature, so to speak.

Pascoal: I agree with what you said about Miles changing directions. I agree so much, you did amazing research and are so sensitive to this matter that I really enjoy your questions.

Jackson: The torrential flow of your ideas reminds of Mozart (or Charlie Parker), but you’ve lived 50 years longer than Amadeus, and your output is unquantifiable at this point. Does archiving your legacy and getting recognition for the volume, range and quality of your works matter to you?

Pascoal: This torrential flow of music, I’m really happy how it is easy for me. I feel it, it goes through me and it’s really fast. The way I see to preserve and internalize it is basically through people all over the world. I really believe my major inspiration is that new children are born every day so I know I’ll be able to play. I basically give it away. The moment I compose it’s out in the world, it’s not even my music anymore. I don’t even name (my tunes). When you compare the recorded part of my career, you mention the thirty-something albums. Let’s say you multiply by 10 each, or by 15, that’s about 500, right? That’s nothing compared to the [unnamed pieces]. So these ones have names, but I am not the one naming them. People tell me, “That sounds like that,” so that becomes the name.

Jackson: How did it feel getting an honorary doctorate from Juilliard, gratifying but slightly ridiculous given that you are largely self-taught?

Pascoal: I don’t think the Juilliard doctorate is ridiculous at all because it is recognition of my creativity. I don’t consider myself a doctor of music but a doctor in creativity, and their recognizing it is a big step. I wouldn’t be a theoretical doctor at all, the one based on the academy and the theory. I would never accept a prize like that, but because it was for my creativity, I’m happy to take it.

Jackson: One of your aural investigations is transcribing human speech. NEC professor Hankus Netsky told me you asked his assistant at the time (vocalist Luciana Souza) to find the most boring sound for you and she chose a cassette recording of Hankus’ aural studies class. You took the topography of his voice and discovered melody there. You’ve transcribed presidential speeches also, part of what you call your “som da aura” concept. This procedure was a big influence on U.S. jazz musician Jason Moran. Are there any sounds you really don’t like and will not think of transcribing, translating and reinventing? Any particularly ugly sounds?

Pascoal: I don’t see any sound as ugly. I see it like a hike in the mountains: Sometimes you meet rocks on the way and you have to go around them, and that’s part of the path. I even feel it is a provocation. What people call ugly sounds, provoke and intrigue me: What can I do with it? Just like the rocks on the rocky mountain. There’s no such thing as an ugly sound.

Jackson: The presidential speech you transcribed — what was it about?

Pascoal: It was not really political, it was a play on his voice, just like everyone’s voice has music and melody in it. You talking to me now I can hear the natural melody. I find the melody when everybody is speaking, then harmonize it and add rhythm. It is just natural, it takes no special effort. I am not into politics very much.

Jackson: You have always drawn a lot of inspiration from nature. Do you see yourself as like a worker bee, pollinating the world with your compositions, preventing our spirits from dying?

Pascoal: I like your idea about the pollinating bee, but I don’t like to label myself or anything I do. For better or worse, I do things without (too much) thinking or planning ahead. I just feel it and I do it. … [I’m not the only one], everyone has a mission. I’m not above or below anyone, I’m just doing what I’ve got to do.

Jackson: No doubt you’d make music from elements of the palm tree, the sand, the waves and crab legs, but If you had to take just one of your tempered instruments to the proverbial desert island and were in perfect health to play any of them, which would you not be able to leave behind: melodica? flute? soprano sax? accordion? kettle trumpet?

Pascoal: I would definitely pick one, but I’d only know when I got there! I would have to pick in the moment and say, “Now I want this one!” I’d play with instruments I built myself like in the beginning (he first played on a pumpkin stem). In nature there’s always been this relationship, playing for the animals. As a kid I’ve always been friendly with and played for the animals with instruments I built and later on with proper conventional instruments like accordion and flutes. I would bring to them and see how they would feel. There was a huge interaction between us, so I invited people to see whether this was true. A few reporters, German and French, have covered this. I would go in front of the lake and play whatever I feel like. I’d choose beforehand what instrument to take. On one occasion I took a flute and three ducks came to check me out, and I realized later that they were the parents, or the responsible ones, and they checked it out and then called for the others. So all the ducks were there. I’d walk to one side of the lake and they would all follow me. Then I’d walk back and then would follow me again, then I would stop and then the ducks would keep singing, then they’d strut away, singing. You can check that out on YouTube, the Hermeto Campeāo documentary. Frogs too, a 1981 documentary recorded in Brazil.

Jackson: So the legends about the session musician pigs, did you really have them in Paramount Studio in L.A. to record Slaves Mass, or was it a field recording? Is the fact that your son Fabio used a toy pig in his percussion kit at the concert a concession since you can’t tour with live pigs … too hard to get them seats on the plane?

Pascoal: Yes, but there is never a need to put the pigs on a plane because we would find them locally. For the studio we found some pigs around town owned by a family and they all came to the studio, the kids too, to make sure the animals were treated with the right care and respect.

Jackson: Is there ever a day when you experience writer’s block, so to speak, when you think, “I’m not sure I’m going to be able to conjure a composition today,” and inspiration doesn’t seem to be in the ether?

Pascoal: Sometimes my consciousness feels that way, but the strong urge never stops.

Jackson: Where does it come from?

Pascoal: It’s 100% intuition that comes from God, the creator, the universe. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…