Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

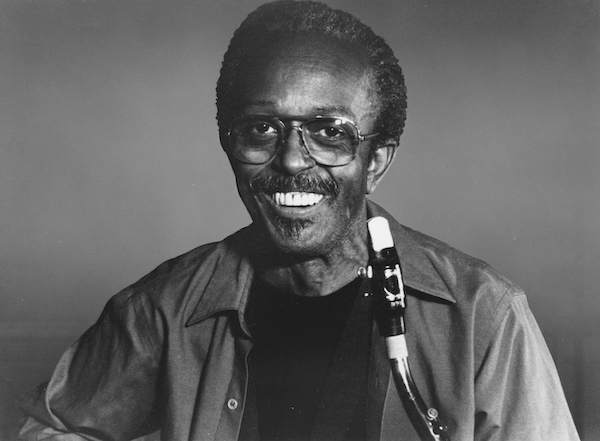

Jimmy Heath (1926–2020)

(Photo: Landmark Records/DownBeat Archives)Jimmy Heath, who died Jan. 19 in Loganville, Georgia, at age 93, was a master of multiple components of the jazz calling.

Not least of Heath’s attributes was his suave, soulful, luminous voice on the tenor and soprano saxophones. As Benny Golson told DownBeat in 2001, Heath “moved through chords, not scientifically, but melodically. He plays ideas. It’s like a conversation, but musical, not linguistic. He has a story to tell, and it’s right in tune with those chords.”

Heath told stories with equivalent panache when operating with the pen. His tuneful, harmonically hip compositions, some 140 in number, appear on two dozen leader recordings and 10 with the Heath Brothers, an endeavor he co-led with bassist Percy Heath (1923–2005) and drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath, his siblings. However small or large the context, Heath’s arrangements embraced meticulous orchestration and improvisational opportunities in judicious equipoise.

Like his lodestar, Dizzy Gillespie, to whom he dedicated the song “Without You, No Me,” Heath also excelled as a communicator, conveying information he’d accrued as a performer, composer and public figure. He did this both formally—helping found the master’s degree in jazz studies program at Queens College—and informally, in off-the-cuff conversations with dozens of acolytes.

“Mr. Heath was always giving,” said alto saxophonist Antonio Hart—Heath’s protégé, student, frequent bandmate and dedicatee of Heath’s “Like A Son”—who now directs the jazz studies program at Queens College. “If you did something he liked, he told you. Everything in his expression was so honest. He always talked about the need to balance science and the spirit. He encompassed all of that.”

Born in Philadelphia on Oct. 25, 1926, Heath received an alto saxophone at 14. After graduating from a segregated North Carolina high school that stopped at 11th grade, he toured the Midwest with the Nat Towles Orchestra for several years. Already intimate with the great swing bands of his adolescence, Heath discovered the revolutionary recordings of Charlie Parker, whose style he emulated so skillfully that he earned the nickname “Little Bird.” Back in Philadelphia, in 1947 he assembled a 17-piece band (personnel included future stars Golson and John Coltrane, trumpeter Johnny Coles, pianist Ray Bryant, bassist Nelson Boyd and drummer Specs Wright) to play bebop charts Heath transcribed from Gillespie’s just-formed big band.

Heath once described his band as a “feeder” for Gillespie, whom he met in 1946 and joined in 1949, after a year with bebop trumpeter Howard McGhee. He remained with Gillespie’s big band and sextet until early 1951. Soon thereafter, he transitioned to tenor saxophone, which he played in a Miles Davis-led combo—alongside his brother Percy, trombonist J.J. Johnson and drummer Kenny Clarke—which recorded Heath’s bop classic “C.T.A.” in 1953. That year, he performed on a Johnson session that marked trumpeter Clifford Brown’s first recording. Heath seemed poised to claim his place as a major voice of the saxophone. Then, in 1955, he was arrested on narcotics charges, and received a four-and-a-half-year sentence.

While incarcerated, Heath led and wrote for the prison big band. After his 1959 release, parole requirements prevented him from traveling outside Philadelphia, forestalling an opportunity to replace Coltrane in Davis’ quintet. At the instigation of Cannonball Adderley and Philly Joe Jones, he signed with Riverside Records, for which he functioned as a de facto staff arranger and led six vivid albums that debuted now-classic tunes like “Gemini” and “Gingerbread Boy.”

Heath returned to New York in 1964, the year Riverside folded. Eight years passed before his next leader recording, The Gap Sealer, a populist “variety package” on which he expanded his tonal palette, incorporating soprano saxophone and flute, electric keyboards, traditional African melodies and funk beats. During that interim, he’d taken steps to move beyond the “mother wit and intuition” upon which he’d previously relied, studying orchestration, string and vocal writing, and extended-form composition with Rudolf Schramm, an advocate of the Schillinger System.

These interests further cohered through his activities with the Heath Brothers—who signed with Columbia in 1978, releasing four strong-selling albums, including the Grammy-nominated Live At The Public Theater, produced by Heath’s percussionist son Mtume—and at Queens College, where he wrote new material for his arrangement and composition students.

Heath’s discography also includes the strong big band albums Little Man Big Band (1992), Turn Up The Heath (2006) and Togetherness: Live At The Blue Note (2014). “To me, the big band is the symphony orchestra of the jazz idiom,” Heath said in a 2014 DownBeat cover story. “It was the fullest and biggest sound you could get before the electronics, with the most power and the most counterpoint playing.”

In 2019, he recorded yet another big band album, which was planned for release this year. Named a National Endowment of the Arts Jazz Master in 2003, Heath remained productive, lucid and trenchant until the final stages of a life well lived. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…