Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

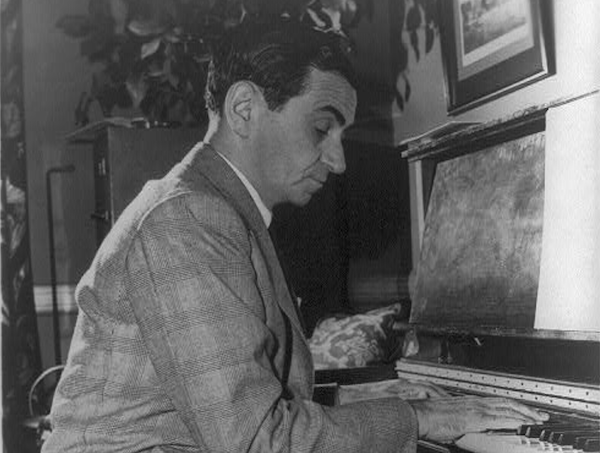

Irving Berlin (1888–1989)

(Photo: Library Of Congress)A song is a mysterious abstraction. It enters the world without identity. It has little character or context. No one can know its destiny, even a pro like Irving Berlin.

We learn in James Kaplan’s biography, Irving Berlin: New York Genius (Yale University Press), that after laboring over a few ideas in the summer of 1932, all Berlin had to show for it was “Say It Isn’t So” and “How Deep Is the Ocean.”

Not good enough, his inner critic fretted. He discarded both.

Fortunately, each tune found the light of day and began to infiltrate the inner lives of unsuspecting listeners. They whistled it, hummed it, sang it, danced to it and, without noticing, enfolded it into their being. That’s how songs work—good or bad, it makes no difference. They quietly attach themselves to moments in our lives and become the lock boxes of our emotional memory.

Kaplan is a good custodian of memory, too. As a youth, he had a fascination with old age as a souvenir of the past that he had missed. And at the impressionable age of 21 in 1972, he came upon a 1909 Berlin record, “Oh How That German Could Love.” For Kaplan, it was “modernism on the hoof. ... formal innovation smuggled into a seemingly banal idiom.”

A cultural historian was born.

The literature on Berlin is small. In interviews, he could be “a little murky, probably because [he] wanted it that way,” Kaplan writes. “He preferred to be the one in control of his own backstory.”

Aside from an early biography by his Algonquin Round Table contemporary Alexander Woollcott in 1925, he declined to cooperate with any a biographer in his lifetime. Laurence Bergreen’s 1990 work remains the definitive Berlin story, supplemented by Ed Jablonski’s 1999 book and a memoir by the composer’s daughter. They are the roadmap of this relatively compact (335 pages) narrative. In place of new revelations, Kaplan writes in the readable voice of an observant journalist and profiler.

New York Genius is part of the Yale series Jewish Lives, but Berlin’s Jewishness is a secondary theme here. Kaplan respects his passion to shed the Old World and assimilate into a new one without any multicultural scolding about deserting his heritage. Berlin just used his background when it was useful. And because he wrote principally from his imagination, not his experience, no genre was beyond reach. His first truly personal work came when the death of his first wife made him a widower at 24. The result was “When I Lost You,” whose craft was impeccable in its simplicity. He understood that repetition is “the soul of a song,” and Kaplan finds Judaic method in that insight. “Reiterated lines sometimes beget music,” he points out, “and much of Jewish musicality grew from the resonance of repeated words.” Berlin’s passion to assimilate never completely displaced his background. “His Jewishness permeated his songs,” Kaplan writes.

Berlin understood his value and how to turn in into power. Composing both music and lyrics, he became the complete auteur. And after becoming his own publisher in 1914, Berlin became a vertically integrated musical empire. His terms were not always easy, though. In Hollywood to score Top Hat in 1935, he was the first songwriter to get a piece of the picture’s profits.

Kaplan’s final chapter is short but moving, covering Berlin’s final 20 years, largely spent alongside his friends and contemporaries in a world that had outpaced them. He came to distrust strangers and held the outside world at bay. It was a remarkable outcome for a man who had been such a cultural lightening rod for so long.

I attended his 100th-birthday celebration in 1988 at Carnegie Hall, but Berlin wasn’t there. Still, I never saw as many legendary figures in one place in my life, singing his songs and hoping for a word from 17 Beekman Place, where the composer lived in New York. But the reclusive Berlin was silent. He left them all alone by the telephone. A good name for a song, come to think of it—one that Berlin wrote it in 1924. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…