Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

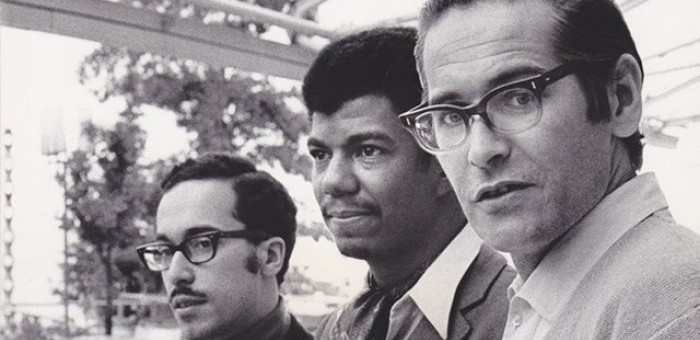

Eddie Gomez (left), Jack DeJohnette and Bill Evans circa 1968.

(Photo: Giuseppe Pino/Courtesy of Resonance Records)They were only together for six months. But the 1968 version of the Bill Evans Trio with Eddie Gomez on bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums is often considered to be among the piano icon’s best, despite having produced only one album in the last half-century, 1968’s Live At the Montreux Jazz Festival.

But as it turned out, there was more material captured on tape by this iconic trio than previously believed. In 2016, the intrepid jazz archeologists at Resonance Records brought the previously unreleased Some Other Time: The Lost Session From The Black Forest into existience, and this year brings the third known recording of Evans, Gomez and DeJohnette to the public with the Sept. 1 release of Another Time: The Hilversum Concert, recorded on June 22 of ’68 before a live studio audience for the Netherlands Radio Union.

DownBeat had the opportunity to catch up with DeJohnette to speak with him about his brief time working in the Bill Evans Trio and its impact on his own storied career.

You had been playing with the Charles Lloyd Quartet prior to joining the Bill Evans Trio. How did you come into that opportunity to replace Arnold Wise?

I was also working with Betty Carter at the time, too. I was in a trio with John Hicks and Cecil McBee. Then shortly thereafter, I had made an audition with Bill and he hired me pretty quickly.

Did you know Bill Evans prior to joining the trio?

I didn’t know him personally, though I knew his music of course. Bill was quite a reclusive guy. He didn’t hang out too much when we were on the road. But I loved his music, and it was such an honor to play with him on some of those tunes I enjoyed on his records. I was only with him for a short time—about six months—before Miles [Davis] called me and I had to go after that. Bill understood this, though.

As a listener, Bill always seemed to take particular care in his choice of drummers. Did knowing the likes of Philly Joe Jones and Paul Motian sat on that stool before you bear any weight to your decision?

Well, not really. I heard the records, so I knew what I needed to do in order to support Bill and what he was doing to shape his conception. It was quite a comfortable fit, honestly.

Did the trio only play in Europe?

Well, we did a few shows in the States as well, including a run at the Village Gate. We did some TV shows, one of which was on the air the day Bobby Kennedy got shot. We played a tribute to the composer Enrique Granados, working in collaboration with the CBS Orchestra for the show Dial M for Music. We played a month-long residency at Ronnie Scott’s in London. It was a good run.

How did your experience in this particular trio inform your future endeavors in the format, particularly your years with Keith Jarrett and Gary Peacock?

For me, it was just a combination of attitude paired with my experience supporting these top-notch artists through the years. It’s all helped me improve more as a musician.

Are you aware of any other recordings from this particular trio?

I have some private recordings, but they aren’t in that great of quality. Other than that, there’s nothing else—that I know of at least. But it’s something that makes it even more fortunate these two concerts were put out by Resonance Records. It’s a nice plus.

How did you feel about hearing this Hilversum concert again as an official release?

I actually like this one better than the Black Forest album. The drum sound on Hilversum was a much better recording. And I also thought the performances by all three of us were much more relaxed and nuanced. Bill sounds particularly great on it. And, of course, Eddie was outstanding as always. I think the trio as a whole jelled really nicely at this concert.

What was your relationship like with Eddie Gomez as a rhythm section?

He was great. No problems at all. We had done some recording dates prior to me coming aboard with Bill, so we were familiar with each other. It was very organic. Since then we had done several albums together, including the group I had in the ’70s called New Directions, which was me, Eddie, John Abercrombie on guitar and Lester Bowie on trumpet.

It must have been quite a juxtaposition to go from the quaintness of the Bill Evans Trio to the electric innovation of the Miles Davis Bitches Brew era.

Well, Miles hadn’t gone totally into it when I first joined. We were still playing straightahead things and would throw a little of the more rockin’ stuff in there. It was a gradual transition.

While 1968 brought about all this change—in terms of how jazz embraced the funk, rock and psychedelic formats—Bill Evans never fully embraced electric instruments in that way.

No, no (laughs). The acoustic piano was his main instrument. That was his voice, so he stayed with it until the end.

Did playing this more buttoned-down piano jazz with Bill Evans inspire your new direction as you began embracing the advent of fusion?

Creative jazz artists are always looking for new ways to make music, express themselves, experiment and play with different people. So that’s all I was doing back then, really. And I still continue to do that to this day. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…