Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“It’s like my memoir as a picture painted in sound,” Lewis explains of his growing body of work.

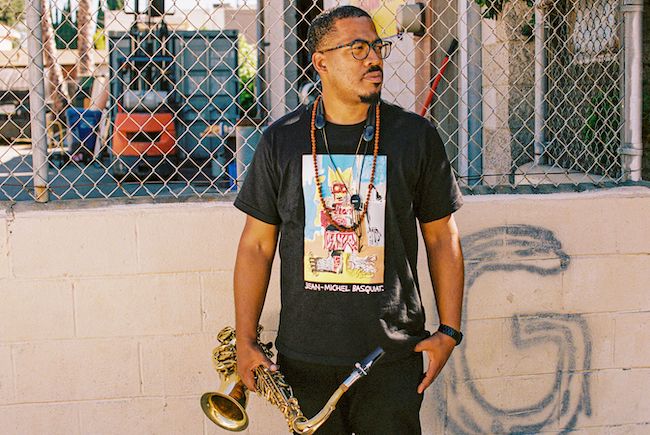

(Photo: Ben Pier)It has been just over a year since this writer last spoke to saxophonist and composer James Brandon Lewis for the cover feature in DownBeat’s June 2023 issue. He was celebrating a recent run of critically acclaimed releases, including 2021’s Jesup Wagon (Tao Forms), which honored the life and work of African American polymath Dr. George Washington Carver, his 2023 boundary-pushing debut with cult label Anti-, Eye Of I, and two DownBeat Critics Poll wins for Rising Star Tenor Saxophone and Rising Star Group.

While he packed for an imminent flight to take him to the first stop of a nationwide tour, he recounted his restless search for creative expression and his journey to reach wider recognition at the age of 40. “I’m constantly searching,” he emphatically stated. “If there’s nothing new under the sun, I’m not interested in that kind of sun.” A year later, as he now joins a video call on a summer morning from a New Jersey coffee shop, it seems as if he has only just returned.

“It’s been a busy year,” he says with a smile while sipping from a takeout cup. “It feels a bit like I’ve been everywhere, just one thing after another.” Busy seems an understatement when the past 12 months are put to paper. Lewis released three albums: a tribute to Mahalia Jackson, For Mahalia, With Love (AUM Fidelity), with his Red Lily Quintet; a new record with his quartet, Transfiguration (Intakt), playing his improvisatory system of “molecular systematic music”; and a debut collaborative album with post-punk supergroup The Messthetics, The Messthetics And James Brandon Lewis (Impulse!). He has also been on tour throughout Europe and the U.S. with the quartet and The Messthetics, as well as finding time to squeeze in sideman sessions on projects led by everyone from trumpeter Dave Douglas to guitarist Ava Mendoza and drummer Ches Smith. To cap it all off, he has just topped the DownBeat 2024 Critics Poll for Rising Star Artist of the Year, joining the likes of previous winners Samara Joy and Melissa Aldana, as well as Rising Star Composer of the Year.

“All of this attention and acknowledgement is totally unexpected and it feels like it’s all coming at once,” he says. “I know there will be an end to it, but I’m enjoying the moment right now.” Indeed, Lewis’ current recognition feels both well-deserved and surprisingly sudden, coming in the wake of over a dozen album releases. His prolific creativity, he explains, has been ultimately driven over the past two decades by a need for self-expression, rather than external validation.

“There’s an urgency I feel inside that I have to get this work out now, regardless of how it’s received,” he says. “I’m always learning and growing and that feeds the music — life and my art are all one, so the music is something I have to do.”

Lewis’ musical education began at an early age, singing along to the sermonic melodies at the Buffalo Church where his father was a pastor, before deciding to learn the clarinet at 9 and fine-tuning his ear by figuring out songs from his favorite Disney movies on the instrument. He later progressed to the saxophone and went on to study performance and composition at Howard University and CalArts, where he was mentored by elders including Charlie Haden and Wadada Leo Smith. “My time in Buffalo and at CalArts taught me about music as a holistic space of influences, without categories or hard boundaries,” he says. “We had Grover Washington Jr., Rick James, Ani DiFranco — music was just music when I was growing up and I’m thankful for that, since it’s hugely informed how I play now.”

Since the independent release of his debut album Moments in 2010, Lewis has certainly embodied a heady range of influences and musical genres within the improvisatory scope of his saxophone playing. Where Jesup Wagon sees him playing incantatory, clear melodic passages — while backed by cornet, cello, the guembri (a Moroccan bass lute) and the mbira (a Zimbabwean thumb piano), Eye Of I is earthy and raw, seeing Lewis play the changes over a genre-hopping set of compositions that span everything from Donny Hathaway’s 1973 soul standard “Someday We’ll All Be Free” to the distorted cacophony of the title track and the yearning tenderness of “Womb Water.”

Meanwhile, For Mahalia, With Love ventriloquises the gospel pioneer’s mighty voice through the clarion call of Lewis’ horn, harking back to those childhood Sundays spent in church, and on The Messthetics And James Brandon Lewis he veers between punchy, punk-influenced rhythmic phrases and full-throated freakouts amid the trio’s driving grooves.

“Each project is rooted in my own story — it’s like my memoir as a picture painted in sound,” Lewis explains. “In terms of the ways that I change my playing style, though, it’s all about what the music requires of me. Transfiguration, for instance, has a set of guiding principles related to my comment on 12-tone music, which means there’s four bars and each bar contains 12 different configurations of notes that never repeat until you get to the next sequence. With The Messthetics, I’m thinking about energy and the rawness of my sound, while For Mahalia was about studying and capturing her sound in dialogue with myself. Every project definitely requires a different mindset — it’s almost like multiple musical personalities that are all unique in and of themselves.”

As well as playing across these diverse projects, Lewis has spent recent years participating in a Ph.D. program at University of the Arts, where he is investigating his changing improvisational methods and the philosophy behind his music. Part autoethnography and part analysis of his discography, Lewis pulls up a section of his thesis to explain his guiding principles.

“I’m not interested in the singularity of my creative process, but I am interested in the natural process of living and how that informs creativity,” he reads. “One definition of music that I like is that it’s the intentional organization of sound. So how do my intentions and what I’m thinking about ultimately communicate themselves through my sound? How do I comment on the human condition through my instrument?”

While the narrative of his musical communication might change from record to record, Lewis’ one constant is the strength of emotion that always sits behind his breath. From the gospel ecstasies of For Mahalia to the knotty solipsism of Eye Of I and the screaming power of The Messthetics, each note passing through Lewis’ horn does so with intent. It is a focus that stems from an early trauma, he explains. “I didn’t release my first album until I was 25 because I wasn’t sure I had anything to say before then or if anyone would listen,” he says. “Then my aunt died, who was always the life of the party, and it made me realize that cliché of life being short. After her death, I had an urgency in my bones to speak my narrative, to live life with the maximum intention.”

On the cusp of celebrating his 41st birthday, Lewis ultimately feels somehow at the start of his celebrated career and also a jazz elder. “Coltrane died at 40 and Charlie Parker at 34, but I still feel super young,” he says. “I’m not trying to reverse time — I enjoy being the age I am and still investigating my instrument. It feels like I’m just now getting my foot in.”

In typical Lewis fashion, he isn’t resting on his laurels but already is busy with plenty more work to come, including a new trio record loosely inspired by the music of Don Cherry, another quartet album and a new project with the Red Lily Quintet. “I never thought I’d be on the cover of a magazine like DownBeat since it was always full of my heroes as a kid,” he enthuses. “So I’m gonna enjoy and embrace this, but when it’s over I’ll go back to my cubby hole to create and get out of the way for the next person to come through.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…