Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

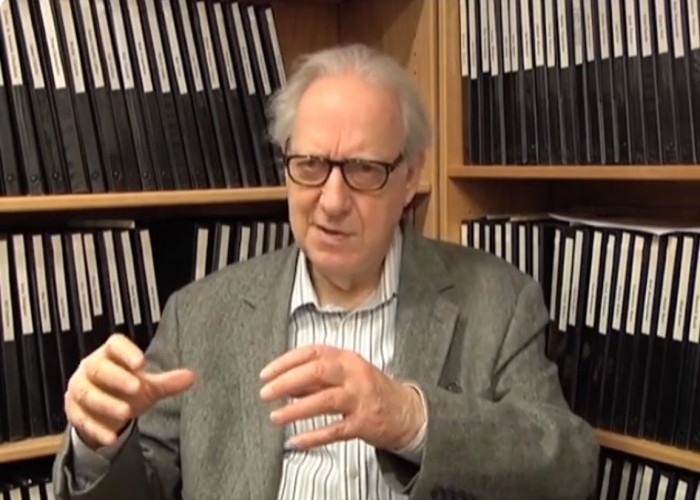

Morgenstern, making a point while being interviewed by Monk Rowe for the Fillius Jazz Archive at Hamilton College.

(Photo: Courtesy Fillius Jazz Archive)Jazz journalist, historian, and 2007 NEA Jazz Master Dan Morgenstern, whose decades of writing and other activities in support of the music earned him the long-standing respect of the jazz circle, died on Sept. 7 at the age of 94 from heart failure. He assumed various roles during a long and storied career, including serving as editor of DownBeat from 1967 to ’73, and from 1976 to 2012 as director of Rutgers University’s Institute for Jazz Studies, establishing it as the world’s leading jazz archive. He was also a prolific and leading writer of liner notes, earning eight Grammy awards, more than any other in that category.

Morgenstern was one of the last of his generation, a particular group of writers and boosters and liner note writers that also included Nat Hentoff, Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones), Martin Williams, Ira Gitler, Ralph Gleason, Leonard Feather and others. Each found a distinct way to champion and capture the music as it was happening, and also to chronicle its history with accuracy. Each attained a stature matching that of the jazz legends they wrote about, interviewed and hung with.

Among these greats, Morgenstern’s voice was arguably the most plain-spoken, and one of the most authoritative. His written approach defined a balance of insight, detail, passion and rare practicality. His writing revealed what for him was a fundamental notion: respect for the musicians and the lives they lived, as much as the music itself. He valued the triumph and the struggle — and refused to allow feelings about stylistic change, an inevitable part of jazz, to infect his words.

In a 1968 DownBeat review he defended a certain guitarist whose popular success was being dismissed by many in the jazz press at the time.

“Like all jazz artists who’ve made it big Wes Montgomery has a sound — hear that good, ye squealers and brayers — a lovely sound … you can’t manufacture that but you sure can market it, and one of jazz’s most harmful myths is that if you do market it, and it sells, some mysterious essential change takes place: art is tainted by success … it is also a myth that you must suffer to create. Do you do your best thing when you are suffering? Is an artist not human?”

Morgenstern loved to share — stories, memories, research. Generations of music writers have written glowingly of the support he offered for an article or a book project, pointing them in the right direction at the IJS. Yet if he sensed a whiff of disregard for factual precision or disrespect for the music, he was not one to temper his displeasure. Trumpeter Randy Sandke, one of many posting tributes to Morgenstern online in the past few days, wrote: “Who’s going to keep us honest now?”

Morgenstern saw himself as a member of the community, rather than being an observer on the side (or worse, above it.) The list of musicians who befriended the writer is a long one, and includes Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Ornette Coleman and, most famously, Louis Armstrong — who nicknamed him “Smorgasbord” (fellow historian Ricky Riccardi has written a lengthy essay recounting their friendship).

“What has served me best is that I learned about the music not from books but from the people who created it, directly or indirectly,” Morgenstern wrote in the forward to Living with Jazz, the 2004 collection of articles and reviews.

Morgenstern’s history is worthy of a screenplay given its Zelig-like moments woven into major vectors of 20th Century history. He was born Dan Michael Morgenstern in Munich, Germany, in 1929. His father, Soma, was a Jewish author and journalist, and his mother was daughter of Danish composer Paul van Klenau. They moved to Vienna, where the pre-teen Morgenstern met various members of the arts community, composer Alban Berg among them. With the rise of the Nazi Party, he and his mother fled to Denmark and eventually Sweden. He kept meeting jazz along the way — on recordings, on the radio and even on stage, memorably catching concerts by Django Reinhardt and Fats Waller (a front-row seat at the latter) in the years before World War II broke out.

Still a teenager, Morgenstern’s familiarity with, and love for the music, grew stronger. After the war ended, his family was reunited in America. He sailed into New York Harbor in 1947, already well-versed in all chapters of jazz history up till then. 52nd Street was his desired destination. His initial career inclination was to be a filmmaker, but his father, who had experienced Hollywood, discouraged him. (“California is a great place to live if you’re an orange,” Morgenstern would say, quoting the comedian Fred Allen.) He took jobs at Time-Life and the New York Times, and after a stint in the Army, attended the newly established Brandeis University in Boston on the G.I. Bill. There he soon discovered George Wein’s Storyville Club, and through Wein, helped bring Stan Getz to campus.

At the end of the ’50s, Morgenstern, back to working in the newspaper world in New York City, found himself turning more and more to freelance jazz journalism. His primary reason was seeking to counter the disparaging music coverage he was reading at the time; “mean-spirited” was his description. He contributed to various jazz publications; an extended article in Jazz Journal on a Lester Young performance at Birdland was read by the saxophonist, who asked to meet the writer. They did, and Prez’s validation was like none other. “It felt like seventh heaven,” he would tell videographer Michael Steinman, who has recorded a multitude of Morgenstern’s stories.

Morgenstern’s reputation grew as did his roles. As New York editor of DownBeat in 1965, he spearheaded a special issue dedicated to Louis Armstrong’s 65th birthday, and helped produce a series of summer jazz performances in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art (a tradition that has been repeatedly revived over the years, including in 2024.) In ’67, he became top editor at the magazine, a position he held till ’73. Three years later, he took on the directorship of the IJS at Rutgers in Newark, where he remained while continuing to write and promote jazz in whatever way possible. Among other feathers in Morgenstern’s hat: hosting and producing television and radio programs; teaching jazz history; authoring two books; and winning Grammys for liner notes that succeeded in revising how the world appreciates such legends as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Fats Waller.

As deserving as Morgenstern was of the awards he notched, in moments of high praise and accolades he often deflected and leaned to humor. This past May, Morgenstern was celebrated at The Jazz Gallery’s annual gala, receiving their Contributor to the Arts Award. He attended the gathering, using a cane and moving slowly and smiling — clearly happy to be in the midst of the scene again. He accepted his statuette graciously, and noted that “Basin Street Blues,” the tune played by that evening’s all-star quintet (Anat Cohen, David Virelles, Nasheet Waits, Rashaan Carter, Wayne Tucker) carried deep personal meaning. “That was the first Louis Armstrong record I ever owned – a 78rpm disc on British Parlophone,” he recalled, and paused, considering his audience. “You guys know what a 78 rpm is, right?” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…