Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

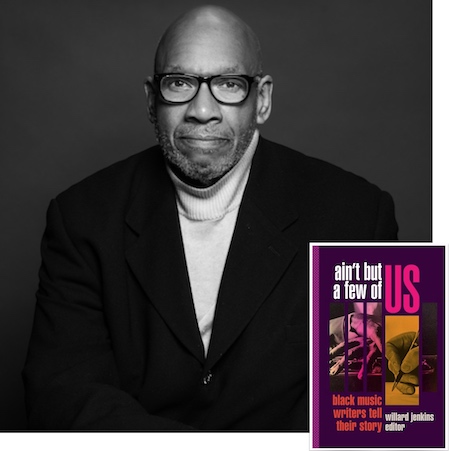

Willard Jenkins’ new book is titled Ain’t But A Few Of Us: Black Music Writers Tell Their Story.

(Photo: David Hartcorn)Writing about jazz, music or the arts more broadly requires a sleight of hand. To write about the overarching culture behind the art is another feat of magic entirely. And let’s give a bit of the trick away: The lens of the person reading the tea leaves, whether providing context or even critique, matters. Their background adds depth.

In Willard Jenkins’ new book, Ain’t But A Few Of Us: Black Music Writers Tell Their Story, the veteran author provides an illuminated glimpse into the world of a surprisingly small, loose confederation of Black jazz writers. When asked what prompted the book, Jenkins told DownBeat in December, “What inspired me to write it was my journey as a writer, clearly understanding the historical origins of this music, and the fact that this music is a definite product of the African experience in America.”

Back in August 1963, “Jazz and the White Critic,” a pivotal essay by Amiri Baraka (then known as Leroi Jones), was published in the pages of DownBeat. In the decades since, the writing (later reprinted in his revolutionary 1967 book Black Music) has served as a rallying cry for generations of Black music writers. The article is referenced several times in Jenkins’ book, and is also included in a richly appointed Anthology section that includes influential texts by Black writers (including Greg Tate, and John Murph and Barbara Gardner of DownBeat).

“We take for granted the social and cultural milieu and philosophy that produced Mozart,” Baraka noted in his essay. “The sociocultural thinking of 18th-century Europe comes to us as a historical legacy that is a continuous and organic part of the 20th-century West. The sociocultural thinking of the Negro in the United States (as a continuous historical phenomenon) is no less specific and no less important for any intelligent critical speculation about the music that came out of it.”

Discussing the inclusion of the piece in Ain’t But A Few Of Us, Jenkins observed that while compiling work for the book, he wanted to “make sure that we included ‘Jazz and the White Critic,’ because [the article] breaks down the core theme of this whole examination, this whole series of interviews.”

Observing that the work, nearly 60 years on, is still “resonant,” Jenkins added, “This is not a book of writers expressing overt grievances, but you’ll find in reading their stories of their journeys that they have experienced certain things that point inevitably to elements of race.”

An intergenerational cadre of writers are represented in Ain’t But A Few Of Us, including Robin D.G. Kelley. In Kelley’s interview, the author and historian cites some of his influences — among them poet Jayne Cortez. “Cortez used to perform [a piece titled ‘U.S.–Nigeria Relations,’ recorded for her 1982 album There It Is] where the line was, ‘They want the oil/ But they don’t want the people.’ Of course, she meant this literally as well as figuratively,” Kelley said. “For many Black intellectuals, the music and the people, the music and the context, the music and the community are inseparable. Once you separate these things, it is easy to make the case that jazz transcends race and history — it is a way of claiming jazz’s universalism, but based on a skewed definition of universal as ‘without connection.’”

The spectrum of vibrant Black voices in Ain’t But A Few Of Us is broad, relaying their experiences in the trenches of the jazz media field — from cub reporters to trailblazers. Jenkins conceded, “There are a few people who have passed onto the ancestry since they contributed to this book,” such as Jo Ann Cheatham (publisher of Pure Jazz), Greg Tate (perhaps most famously a critic for The Village Voice), Jim Harrison (publisher of the Jazz Spotlite News) and Bill Brower (who wrote for a number of publications including DownBeat and JazzTimes).

“And then, of course, there are a lot of seniors who’ve contributed to this book,” Jenkins said. “People like A.B. Spellman. For me, it was important to have him because not only does he contribute an interview, but he also contributes an anthology piece. And because a number of these writers, Greg Tate and others who come along … cited A.B. Spellman as being an inspiration. In fact, the two people who were cited as being the most inspirational consistently were Amiri Baraka and A.B. Spellman.”

Ain’t But A Few Of Us also paints a vivid picture of how Black women writers have fared the world of jazz. According to Jenkins, first-person narratives from writers like Tammy Kernodle, Farrah Jasmine Griffin, Karen Chilton, Bridget Arnwine and Angelika Beener are a crucial to the book. “I think a more diverse core of writers reporting on the music will help to broaden [jazz]. There’s a huge gender gap in terms of who’s writing about this music. And I wanted to make sure that we incorporate as many women writers as we could in this dialogue.”

The book serves as a testament to the experiences of a rare few, proof-positive that Black writers and editors are not alone.

“This isn’t a volume … citing the kind of overt racism most white folks can recognize,” Jenkins said. “For example, in Robin Kelley’s chapter, he speaks to submitting a piece to The New York Times about the very positive efforts of the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium, a Black Brooklyn coalition of jazz activists. The response of his music editor? Something to the effect of, ‘Who is going to believe this, that Black folks are supporting jazz like this?’ That’s the kind of racism, white supremacy, we far too often, even in the 21st century, have to unfortunately call their attention to. That piece [never published by The Times] is Robin’s contribution to the Anthology section.”

Jenkins reiterated, “This is not a book of grievances. This is not a book of aggrieved writers expressing their issues with elements along their particular journey. But it is a book of writers who, because of who they are, have experienced certain things and may have experienced certain resistance.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…