Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

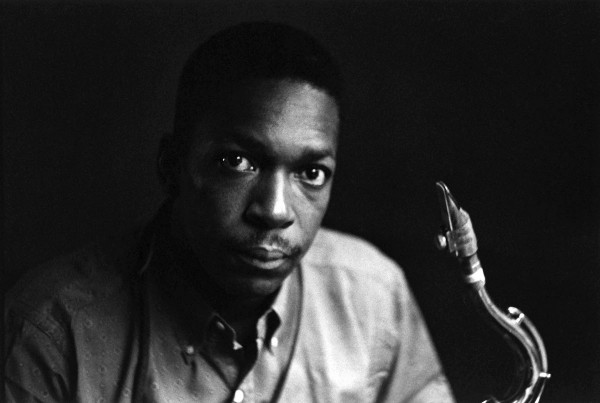

In 1958, John Coltrane turned 32. He’d just rejoined Miles Davis’ band after a sojourn with Thelonious Monk, and had in the previous year finally freed himself of his addiction to drugs and alcohol.

(Photo: Esmond Edwards/CTSIMAGES)Perhaps the most striking thing about the current resurgence of interest in John Coltrane is the extent to which it focuses not on masterworks, but on transitional stages of the saxophonist’s development.

Some of that’s a result of the recently discovered material on Both Directions At Once, which suggested that the radical innovations of Coltrane’s later work already had taken root by 1963. And when the compilation 1963: New Directions placed those lost tracks alongside the other recordings he made for Impulse! that year—the lyric balladry of “They Say It’s Wonderful” with Johnny Hartman, the harmonic adventurism of “Dear Old Stockholm” and the prayer-like hush of “Alabama”—it was easier to recognize the individual strands that, once woven together, would form the fabric of 1964’s A Love Supreme.

Just as 1963: New Directions illuminates a critical phase of Coltrane’s musical quest, the eight-LP set Coltrane ’58: The Prestige Recordings captures him at a pivotal point in becoming one of jazz’s most influential leaders and soloists.

Coltrane turned 32 in 1958. He’d just rejoined Miles Davis’ band after a sojourn with Thelonious Monk, and had in the previous year finally freed himself of his addiction to drugs and alcohol. Having risen from the ranks of the promising to the realm of the prominent, he was in almost constant demand; the seven sessions he cut as a leader for Prestige were but a fraction of the 20 recording dates on his calendar that year (including five for Columbia with Davis’ band). Coltrane was just a year away from recording both Kind Of Blue and Giant Steps, and at its best, Coltrane ’58 provides a sense of how the saxophonist managed that particular ascension.

Notably, 1958 also was the year the late Ira Gittler, writing in DownBeat, coined the phrase “sheets of sound” to describe the torrents of notes the saxophonist would unleash as he tried to cram all the discoveries he gleaned from chord stacking into just a couple beats. Coltrane ’58 includes one of the most famous examples of this, the saxophonist’s fevered, double-time take on Irving Berlin’s ballad “Russian Lullaby.” But the set’s real treat is a transcription of his solo on the “Night Train”-ish blues “By The Numbers,” which makes visible the rhythmic variety of Trane’s fleet-fingered runs.

Given that he didn’t have a working band of his own at the time, a certain inconsistency of tone might be expected, but there only are a few moments across these 37 tracks where the music loses its focus. Even then, it’s only momentary, as on “I’m A Dreamer (Aren’t We All),” where, after trumpeter Wilbur Harden audibly falters, Coltrane charges in with a statement aggressive enough to lift to the band’s energy and make the silences in Harden’s solo seem like an intentional contrast. It helped that four of the seven sessions here were cut using Red Garland’s trio, with bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Art Taylor, as Coltrane knew Garland and Chambers from Davis’ quintet, and had a tremendously simpatico relationship with both. But apart from the leader, Chambers was perhaps the most valuable player here, turning up on all but one track and providing the sort of rhythmically reliant, harmonically incisive grounding Coltrane needed to concoct his own questing solos.

Chambers’ sound is also a useful yardstick for rating the audio quality of Craft’s remastering on these sessions. Although the original recordings, made by Rudy Van Gelder at his famous Hackensack, New Jersey, studio, long have been prized for their clear, uncluttered sound, there’s an element of transparency in Paul Blakemore’s remastering that the CD versions on Prestige lack. Listen to “I See Your Face Before Me,” the first stereo track on the set, and the improvements are immediately obvious; the soundstage is so well defined that listeners almost can point to where Chambers was standing, while his tone is deep, rich and natural, particularly on the arco solo, offering a strong, resonant sound, instead of the CD’s resiny rasp. Close your eyes, and you might imagine yourself on the sofa in Van Gelder’s living room, listening intently as Coltrane and company conjure a vision of jazz’s future. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…