Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

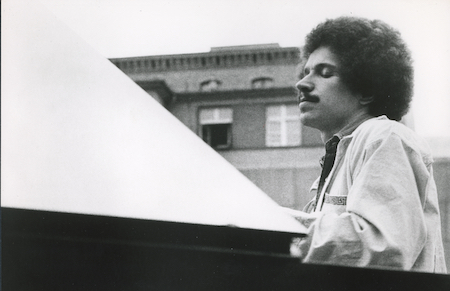

“Keith’s thing was startling,” pianist Craig Taborn says of Facing You.

(Photo: Courtesy ECM Records)A half century has passed since Keith Jarrett released his first solo piano album, Facing You (also his first recording for ECM), which altered the course of jazz. With the announcement last fall of Jarrett’s retirement following strokes he suffered in 2018, the 50th anniversary of Facing You becomes cause for both celebration and a bit of sadness.

“For me, it changed everything,” pianist Kenny Werner said of the seminal album. “He introduced a totally fresh way of playing over his changes. It sounded totally original.”

Just 26 years old when Facing You came out, Jarrett had come to the fore with Charles Lloyd on the wildly popular 1967 album Forest Flower and had gone on to form his own trio and quartet, in addition to working with Miles Davis on Bitches Brew and Live/Evil in 1970–’71. The pianist originally planned a solo album for Columbia, but the label dropped his contract, so when ECM’s Manfred Eicher extended an invitation, Jarrett jumped.

“If I hadn’t found him there would still be no solo albums, no Facing You, let alone a successful triple album,” Jarrett told Down Beat in October, 1974, referring to the subsequent 1975 set, The Köln Concert.

Though never as popular as Köln, which so far has sold more than 4 million copies, Facing You was the beginning — step one of a long journey that has led listeners and musicians to a vast, robust, new musical territory.

Recorded in Oslo, Norway, on Nov. 10, 1971, during a day off from touring with Davis, Facing You was released in March of the following year. It was a turbulent time. The Vietnam War (and the protests against it), Watergate, the assassination of Israeli Olympians by the Palestinian terrorist group Black September, the Northern Ireland conflict, racial strife in the U.S. and a younger generation in open rebellion against the old order — all of this dominated the headlines.

And yet it was also a time of tremendous optimism, change and possibility, as Apollo 17 beamed back photography of Earth, the Equal Rights Amendment was passed by Congress, and Eastern spirituality and Western psychology had a baby called the human potential movement, all of it ushering a shift from ’60s communalism to the primacy of the personal that flowered in the ’70s.

Indeed, Jarrett can be read as an icon of that era, though his profound and original project surely transcended the treacly self-absorption of the New Age pianists who later claimed him as an inspiration. Sitting alone at a grand piano on a concert stage, Jarrett was facing the keyboard, as it were, but also facing you, the listener, with an open heart. It was as if Jarrett coolly observed clouds of musical thought pass by — snippets of jazz, classical, folk, country, blues, boogie-woogie, pop, gospel — and somehow pulled them down to Earth for all to see.

And even more miraculous, it all made sense, which seemed to suggest that the universe was not random at all, but actually ordered already, if only you just listened hard enough. Yes, others had played solo piano before, Art Tatum and Cecil Taylor, for example. Chick Corea and Paul Bley would both release solo albums within months of Facing You (also thanks to Eicher). But no one had ever heard anything quite like Jarrett.

“Keith’s thing was startling even amidst the Chick one, or Paul Bley’s albums,” reflected pianist Craig Taborn, whose recent solo effort, Shadow Plays, takes Jarrett’s influence to a new level. “It was still like, ‘What’s this? What’s this one?’ That’s what always hits me about Facing You. It sounds fresh that way. A lot of how pianists play today owes so much to that.”

The fact that Facing You was released in an era dominated by electric jazz-rock fusion seeking to reclaim young listeners from rock (Quincy Jones’ Smackwater Jack and Davis’ On The Corner topped the 1972 jazz charts), it’s all the more intriguing that such a contrary strategy would succeed. But Jarrett drew in non-jazzers with rumbling, soulful ostinatos and unabashedly gorgeous melodies in the mode of 19th century romantic piano music.

Perhaps even more impressive than his reconciliation of jazz and rock, Jarrett also made peace with the seriously regarded “free” music rising in opposition to straightahead jazz by devising, as Werner points out, “a new way of playing on changes” that was both inside and outside. Instead of declaring a tune then improvising on its form, he improvised tunes, then invented forms on the fly by creating variations on a motif here, a chord progression there, or a wild excursion out of nowhere, then returning to whatever suited his fancy, whenever he felt like it, with long breathing spaces in between.

Critical reception was ecstatic. In a review for Rolling Stone that also addressed Jarrett’s American quartet albums Expectations and Birth, the late Robert Palmer declared that Facing You “may well be the finest album of jazz piano solos since Art Tatum left us, and it is without a doubt the most creative and satisfying solo album of the past few years.” The Canadian jazz magazine Coda called Facing You “a classic that stands as the ultimate achievement of the artist who has, after years of searching, found himself.”

As both Taborn and Werner observe, Facing You still sounds remarkably fresh. With eight almost totally improvised tracks totaling just 46:14, it is more compact than many later albums, with fewer long vamps and more pre-composed material. Yet, like everything that followed, the album projects that sense of precarious, in-the-moment possibility that became Jarrett’s trademark.

From the opening track, “In Front” — which starts as if we’ve caught the pianist in the middle of a thought, then rides an ambiguous, broken, two-handed rhythm to churchy, ecstatic joy — to the album’s resolution, “Semblence,” which returns to the same feel, but with speedy runs and a hard, glassy surface, Facing You feels like one long, coherent conversation with a muse whose mercurial moods shift easily from serene to rhapsodic, from troubled to spacey, from melancholy to sublime.

Its notes still ring around the world. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…