Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

In Memoriam: Ken Peplowski, 1959–2026

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

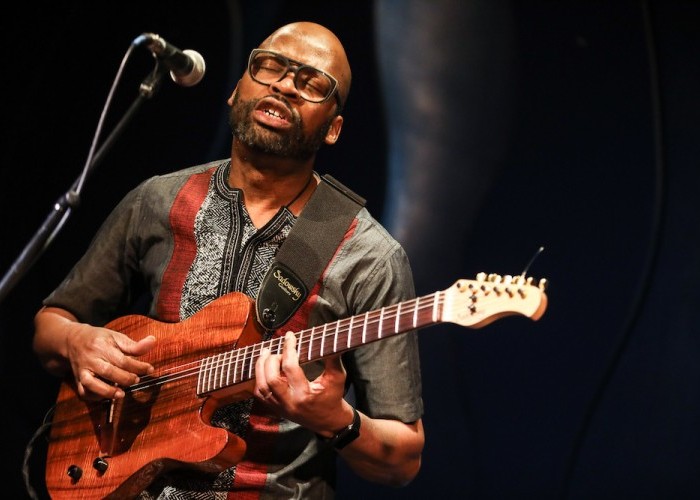

Lionel Loueke incorporates styles and sounds from other instruments into his guitar playing.

(Photo: Mark Sheldon)For guitarist Lionel Loueke, the title of his new album—The Journey (Aparté Music)—isn’t merely a metaphor. It reflects both his odyssey from childhood in Benin to his current life as a globe-trotting jazz star while also mirroring his musical development.

“My CDs are all different, and I like them that way,” Loueke said in his soft, French-accented voice. “This one in particular is really different, because it’s a resumé of all I’ve done in the past, and a continuation of what I’m doing now. It’s the first time I’m combining classical musicians and classical musical instruments with jazz and African instruments, all on the same project. It’s the first time I’m putting a CD out without a drum set; it’s all percussion. So, yes, we definitely have a different character.

“This is about the music; I wasn’t focusing on ‘jazz’ or ‘classical’ or ‘African.’ It’s a different project—more song-oriented, more words, more singing.”

It’s also more personal, as Loueke touches on his family life and background. “Molika,” for instance, takes its title from the names of his children (Moesha, Lisa and Mika), while “Bouriyan” references Afro-Brazilian culture in Ouidah, the city in Benin where his mother was born. There are lyrics in French, but more in Fon, Mina and Yoruba, languages spoken in Benin. Above all, the album reflects Loueke’s life as an immigrant, and his feelings about the migrant crisis in Europe at the moment.

“I don’t like to talk about politics,” he said, “but this issue is something that has interested me for a long time because there’s some ignorance when it comes to immigration. You don’t leave your place, you don’t get on a boat or a ship to cross the Mediterranean if you are not desperate. You do it because you know that there is nothing else left for you where you are. You are ready to die. You prefer to die on the sea, basically, rather than wait for them to kill you. It takes courage. It’s not something where you just wake up one day and go.”

As befits someone whose music is often a model of economy, Loueke’s lyrics are almost aphoristic, evoking great feeling with few words. “Bawo,” which is Yoruba for “how,” asks, “How have we come to this? Modern-day slavery/ And climate disruption push/ Humanity to the roads of exile.” Yet the music, rich with complex polyrhythms, carries not anger but the bewildered resignation of a man shaking his head at the state of things.

“Those are things that are happening, and the responsibility—I’m not blaming just the politicians. I’m blaming everybody, including myself, you know?” he said. “And this project is working to change our ways. The whole CD, while you listen to it, nothing is aggressive. The CD I did before, called Gaïa, is more rock-oriented. But here, a song like ‘Vi Gnin’—about a child who lost his mother in a war—is presented in a gentle way.” And gentleness is important, Loueke said, because it encourages deep listening: “We can change the world by talking to one another, by trying to understand the other person. And that’s what I try to present.

“On the song ‘Reflections On Vi Gnin,’ which was completely improvised, there’s just sound. I’m not using any actual words. They’re sounds, because when you listen to music, if you don’t have the lyrics or you don’t understand the words, you have different images coming through your mind. This is what it’s about here. If you hear ‘Vi Gnin,’ maybe you’ll say, ‘It’s beautiful.’ But you can’t say, ‘Vi Gnin’ is a happy song. And for me, that’s the power of music. It’s not always about the lyrics; it’s about the atmosphere you set up.”

Loueke, who currently lives in Luxembourg, credits much of his journey to his search for musical knowledge and experience. “I moved to the United States to study jazz,” he said. “The reason I moved to Paris was the same thing—to study jazz, and to study classical. I turn to Europeans so I can learn new things, so I can blend better, to put two different spices together for the flavor.”

After four albums for Blue Note, Loueke switched to the classically oriented French label Aparté for The Journey. He once again worked with Robert Sadin, who produced his 2006 album, Virgin Forest.

“Bob Sadin had the great idea of proposing to me to go into the studio for three days and just record by myself,” Loueke said. “Usually, I go into the studio with a band. So, that’s how we started this project. I played by myself, and then we started developing. And I was like, ‘Man, I’m feeling this. Maybe I can add another guitar or some percussion.’ Or we just redo it with different musicians, based on what I recorded in those three days.”

“I’ve known Lionel for a long time,” Sadin said. “He has a great sense of community. If he’s with other musicians, he tries to find a common ground, and that’s great in a lot of situations. But for his album, I felt that it was important not to find common ground, but just reach into himself.

“So, he played alone, and he defied every convention. He was precisely on time or early for everything. An 11 a.m. session? Wham, he’s ready to go. And unlike almost anything I’ve done, we never needed a second take for anything being not quite right. We might want one to take a different approach, but his playing was just—‘flawless’ is not a word I like to use, but there was never a take that wasn’t great.”

Loueke plays acoustic guitar for most of the album, which is not only a change from his usual recorded sound, but also represents a change from how most listeners would expect an acoustic guitar to sound. On the album opener, “Bouriyan,” Loueke plays percussively, pinging harmonics, muting the bass strings with his hand, even slapping the strings like a bass player.

“That slapping on the guitar [is something] I’ve been developing for the last few years,” he said. “I’d never done a sound like that on an acoustic guitar. Usually, I do it on electric with my effects. So, I tried it on acoustic, which for me sounds more naked, and more real.

“That type of playing brings me back, to back in the day when I was a bass player. Before I played guitar, I was a bass player. I’ve always loved bass, and so many of my songs are based on a bass line.” He laughs. “I think of myself as a guitar player/frustrated percussion and bass player. Because bass is really involved in what I do.”

On The Journey, however, all the bass playing is provided by Pino Palladino, whose credits include work with Herbie Hancock, Jeff Beck, José James and D’Angelo. “In one note, you know it’s Pino,” Loueke said. “A really warm sound. And on top of being one of the greatest [musicians], he’s just a great guy. When I asked him, he was in London. He took the train, came to Paris, recorded with us, and went back.”

Palladino’s playing on “Bouriyan” is spare and supportive, undergirding the guitar line where needed, and laying out when not. But some of the track’s tastiest moments come when, instead of playing the obvious root, he plays something more melodic, slyly flipping the harmony. “What I love about Pino is how he always finds what’s missing, or what he can bring to lift the music,” Loueke said. “I try to think that way, and that’s my approach to music. If I feel that I cannot bring anything, I won’t do it.”

“Pino was completely relaxed,” Sadin said. “He was not trying to think, ‘Where is Lionel going next?’ In a way, that enabled him to bring more of himself, because he was not trying to adjust, but bring his thing to bear on the music.”

Fitting into Loueke’s groove is no small thing, Sadin added, because the guitarist’s timing is so highly developed and specific. “His phrasing is so extraordinary that it’s hard for people to adjust to his playing,” he said. “It’s so subtle that it really goes beyond what most people can follow, because he’s combined so much traditional African music, so much jazz, and [other genres of] music.”

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…