Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

In Memoriam: Ken Peplowski, 1959–2026

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

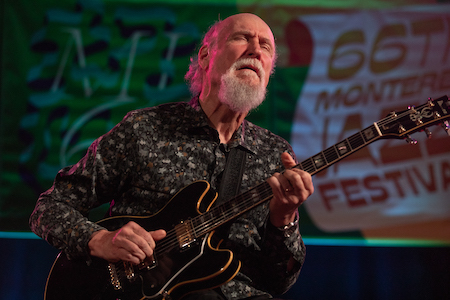

John Scofiled was the showcase artist at this year’s Monterey Jazz Festival.

(Photo: Patrick Tregenza)The 66th Monterey Jazz Festival (including the cancelled festival of 2020) was the final one to have Tim Jackson as artistic director, a post he has held since succeeding founder Jimmy Lyons in 1992. Jackson pulled out all the stops during his last hurrah, booking a long list of major jazz artists. This year Monterey featured high-quality music at five venues (almost back to its pre-COVID level) and, unlike many other festivals, more than 95% of the performances were jazz.

Held at the same Monterey Fairgrounds, where every edition of the festival has taken place since its debut in 1958, there was so much going on simultaneously that it was easily possible for a half-dozen people to have completely different Monterey experiences. One had to devise their own road map to make sure that they did not miss a high point.

Guitarist John Scofield, this year’s showcase artist, was one of several major names who appeared multiple times. He led his quarter Yankee Go Home, wailed with keyboardist Larry Goldings with the rollicking Scary Goldings and played a set of solo guitar (utilizing occasional pre-recorded tracks for accompaniment). The fest’s artist-in-residence, the always-passionate altoist Lakecia Benjamin, guested on trumpeter Terence Blanchard’s partial retrospective of his career, sitting in with the MJF Women In Jazz Combo and the Next Generation Jazz Orchestra, and leading her group Phoenix.

Pianist Gerald Clayton appeared to be even busier. He performed in a trio with bassist John Clayton (his father) and drummer Jeff Hamilton. As leader of the Next Generation Jazz Orchestra, he had the college ensemble sounding much closer to the Mingus Big Band (including wild sequences where all of the horn players soloed together) than to the typical stage band. In addition, he had opportunities to assist in the music of two earlier Monterey heroes. 90-year-old altoist John Handy, the star of the 1965 Monterey Festival, sounded fine playing “The Nearness Of You” and even included a few of his trademark stratospheric high notes. Clayton was also performed with the Charles Lloyd Quartet. Their set concluded with Lloyd playing a new version of “Forest Flower,” the song that excited Monterey audiences in 1966 and gained a standing ovation 57 years later.

In addition to Clayton, there were many major pianists at the Monterey Jazz Festival this year including Herbie Hancock, Kris Davis, Jamie Cullum, Taylor Eigsti, Sean Mason (with swing singer Catherine Russell), Billy Childs and James Francies. Three in particular were in memorable form.

Benny Green performed solo and mostly paid tribute to past giants of the 1950s and ’60s including Tadd Dameron, Horace Silver, Bobby Timmons and Oscar Peterson. Being in an unaccompanied setting meant that he often supplemented his boppish chords and rapid octaves with some light stride. Among the songs that Green uplifted were “If You Could See Me Now,” “Come On Home,” Kenny Barron’s “New York Attitude,” the ballad “Once Upon A Time,” “When Lights Are Low,” “Ruby, My Dear” and James Williams’ “The Soulful Mr. Timmons.” Throughout his pleasing set, Green played creatively within the foundations of hard-bop, telling stories between the songs.

Connie Han, with bassist Ryan Berg and drummer Bill Wysaske, offered a very different approach, stretching and breaking through the tradition while still always being connected to jazz. She consistently displayed impressive technique, a vivid imagination, and a powerful style. After playing a heated rendition of “Yesterdays” that included many dense chords, she swung hard on Wysaske’s “Boy Toy,” paid homage to McCoy Tyner in her own way on “For The Og,” played what she called “an abstraction” on Stephen Sondheim’s melancholy ballad “City Women” and performed a medley of three songs from her recent release Secrets From Inanna. The unpredictable music ranged from coherent violence to tender moments with plenty of tight interplay by the musicians, always holding onto the audience’s interest.

While it had plenty of competition (including a triumphant set by singer Samara Joy, Ambrose Akinmusire’s commissioned piece featuring singer Oumou Sangaré, the Lew Tabackin-Jeremy Pelt pianoless quartet and Catherine Russell’s swinging performance), the most memorable hour of the weekend was provided by pianist Sullivan Fortner at one of the smaller stages. Joined by bassist Tyrone Allen and drummer Kayvon Gordon, the performance started with Fortner playing a brief version of his theme song on piano and organ. He then displayed his encyclopedic knowledge of all styles of jazz during a series of wide-ranging pieces, with his dazzling technique being matched by his creativity. On “Nine Bar Tune” (he joked that he was not great with coming up with song titles), Fortner showed that he was well aware that jazz piano did not start with Bud Powell, reaching back to 1920s stride in an often-humorous fashion. On Deford Bailey’s “Davidson County Blues,” his boogie-woogie piano playing often sounded like a futuristic version of Cow Cow Davenport. Among the other works that he explored were a vintage Latin piece, a classical composition by Gabriel Fauré and a very slow version of “In A Sentimental Mood” with the latter sounding like a conversation between his two hands. Throughout his set, Fortner effortlessly dug into a variety of styles, not recreating the past but creating an eclectic mixture that looked towards the future with wit, sensitivity and more than its share of surprises.

Kendrick Scott’s trio with Chris Potter and Reuben Rogers, the film Inside Scofield and Terri Lyne Carrington’s New Standards were on the other stages at the same time, but virtually no one left during the Sullivan Fortner performance. As with the best sets from the 66 years of the Monterey Jazz Festival, his wondrous playing left the audience spellbound. DB

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…