Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

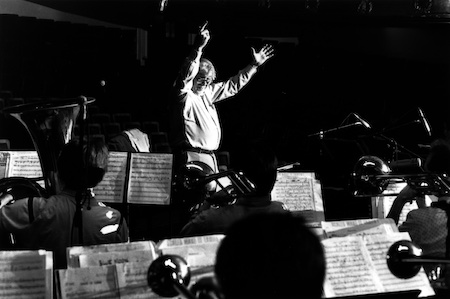

Gunther Schuller, founder of NEC’s Third Stream department, now known as Contemporary Musical Arts.

(Photo: Courtesy NEC)Gunther Schuller coined the term Third Stream in a lecture at Brandeis University in 1957, by which time he had long been developing a synthesis of jazz and classical music. But it wasn’t until 1972 that a Third Stream department was established in the academy. That was when Schuller, who had assumed the presidency of Boston’s New England Conservatory five years earlier, took the plunge.

His first act was to hire pianist and radical thinker Ran Blake as chairman. Blake, who ended up holding that post for 22 years, had studied with Schuller at the legendary School of Jazz at Lenox, Massachusetts, and, in 1962, became a subject of Schuller’s analysis in liner notes for his epic album The Newest Sound Around. As chairman, he ran with the Third Stream concept.

Today, Blake said, “the definition has broadened.” On the 50th anniversary of the department, its name — which in 1992 changed from Third Stream to Contemporary Improvisation — has become Contemporary Musical Arts. The change comes amid an ongoing expansion in the department’s scope, which now includes applying to all types of music what had been the goal of unity between two.

In the forefront of promoting this ecumenical approach has been department co-chair Hankus Netsky. A fixture at the school, off and on, since he began as a student in 1973, Netsky has found that the best way to address incoming students’ parochial inclinations was with a series of rhetorical questions.

“I always say, ‘What do you not want to learn? You’re not going to study form from Schubert and Beethoven? You’re not going to study polyphony from Bach? You’re not going to study Debussy? I don’t think we’d have Miles Davis without Debussy. Or Messiaen? Or Louis Armstrong? What can you ignore?’ It doesn’t make sense to have music education in a tunnel-vision way.”

Music being an aural art, students’ minds are opened through their ears. For undergraduates that process begins with Blake, who literally wrote the book on the subject with Primacy of the Ear. Students develop “long-term memory,” both “melodic” and “harmonic,” building familiarity with a piece of recorded music through a painstaking process of repetitive listening until every nuance is assimilated. Then they figure out what they want to do with it. Personal recording devices are required; paper is eschewed.

“They get trial by fire,” Netsky said.

Blake said that weaning students from the printed page had not always been easy: “People who were used to learning music visually were very startled that I wanted them to hear a Billie Holiday piece over and over, sing or whistle it, put it on their instrument. To this day, many people adore this approach and know it’s the right one. But there’s still resistance on the part of students.”

His response? “Save your eyes for Picasso and Grandma Moses.”

Farayi Malek, a singer who studied at NEC and now teaches there, recalled working with records by singer Chris Connor (whom Blake dubbed “his favorite non-Black musician”). “We’d practice them and perform them, learn them just like the record,” he said. “I’d learn them on piano — try to learn the exact voicings and mimic the inflection of her voice. We were really trying to understand the fullness of the recording, every detail. A lot of times he’d point out areas where we’d go in deeper.”

Deep dives are also a mark of Netsky’s aural-skills course, though he comes at the subject from multiple angles. Students learn to play gospel piano and improvise on “Mood Indigo” while playing seventh chords, among other things.

They advance from hearing the harmonically simple (Jimmy Yancy playing “How Long Blues”) to the complex (Charles Mingus’ “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”). They absorb music like the bebop language of Oscar Pettiford on “Perdido.”

“I’m not giving them a lead sheet,” Netsky said with a laugh. “It’s wrong, anyway.”

Graduate students, as needed, take aural-skills courses. But the core of their training, developed by Netsky, is four semesters of Third Stream Methodology. The Third Stream moniker has been retained, he said, because it’s “kind of fun” and a nod to Schuller and Blake.

It recognizes that the course series embodies their ethos.

The first two semesters, Netsky said, are “about becoming a diverse community.” Students from far-flung locales work together on projects through which they expand their knowledge by learning about their respective cultures. The third semester focuses on disparate improvisational traditions. The fourth, among other things, uses the work of varied artists — from Ornette Coleman to Stravinsky to James Brown — as conceptual frameworks in which the students develop their own voices.

Netsky, a driving force in the resurgence of klezmer music and the leader of a Jewish-music ensemble, has pushed for the expansion of ensembles in the program.

Currently, there are nearly 20, among them groups based on Irish, Middle Eastern, Persian, Brazilian and West African traditions; bluegrass, rhythm and blues, and indie, punk and art rock genres; the African diaspora in America and the Caribbean; contemporary chamber music; and the work of Thelonious Monk. Iconoclastic improvisers Anthony Coleman and Joe Morris lead ensembles.

Morris, a noted guitarist who is celebrating his 20th year at NEC, teaches a pioneering course, Properties of Free Music, in which he distills the work of avant-garde innovators into concrete methodologies. His ensemble puts his theories into practice, supplying students with a set of tools for forging an improvisational identity in a genre that steers clear of rules.

Not everyone who studies with Morris intends to concentrate on free music. One notable example is Sarah Jarosz, the singer-songwriter and instrumentalist. Jarosz has won four Grammy Awards in the Folk, Americana and American Roots categories.

But before that, she took private lessons and the ensemble class with Morris, skillfully playing Anthony Braxton, Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman compositions on her octave mandolin — and, in the process, informing her work in her chosen genres. In that, she is emblematic of the department’s efforts.

“The most interesting thing about CI is the diversity of students engaged in something they’re not used to doing,” Morris said, invoking the shorthand for Contemporary Improvisation, the department’s former title. “It brings out a quality of those disciplines that’s pretty amazing — and brings a quality of synthesis and difference to each one of those students.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…