Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

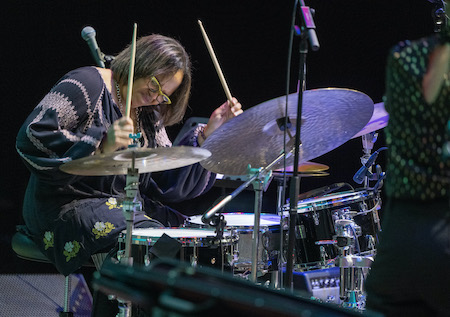

Terri Lyne Carrington curated the opening-night concert of New York’s Winter Jazzfest at City Winery.

(Photo: Steven Sussman)After a two-year hiatus imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, New York’s Winter Jazzfest returned to live performance Jan. 12–17 on a grand scale. Operating in parallel to the annual APAP (Association of Performing Arts Professionals) convention, the festival offered a global cohort of performers — some 90 bands from several continents. In addition to long-standing “marathons” on Jan. 13 (36 acts at seven stages in six downtown Manhattan locations) and Jan. 14 (33 acts at seven venues in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn), WJF sponsored multi-performer concerts and showcases at Loisida’s Nublu and Greenwich Village’s Le Poisson Rouge and two panels at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem, including a discussion of “the current status of gender equity in jazz.”

Ancillary events of note included a four-day, 27-set “solo piano festival,” co-sponsored by Fazioli at Klavierhaus, booked by veteran jazz impresario Jim Luce (the impressive roster included only two women); showcases sponsored by various managers; 10 international groups at Global Fest at Geffen Hall in Lincoln Center; and several inspired one-offs, among them a “Gnawa meets jazz meets members of the David Bowie and David Byrne bands” at Rizzoli Bookstore.

No single journalist — not even two or three — can hear enough to extract larger meaning from the entire proceedings. But as a general observation, WJF’s schedule reflected its institutional commitment to racial, gender and stylistic diversity and inclusion, with concerts by practitioners, primarily young, representing almost every jazz genre and sub-genre save so-called “straightahead,” a strange omission in New York, where the canons that constitute the jazz continuum, nurtured by living masters of the idiom, intersect daily with multiple permutations of an aesthetic underpinned by Ornette Coleman’s mantra “tomorrow is the question.”

An exception was the well-attended opening night concert at City Winery, curated by Terri Lyne Carrington in celebration of her recently published New Standards: 101 Lead Sheets By Women Composers (Berklee Press), and the excellent parallel CD New STANDARDS Vol. 1, which contains 11 sparkling interpretations of tunes contained therein. Carrington convened an all female-or-binary octet including the seven awardees of the inaugural 2022 Next Jazz Legacy grant, who were followed by 14 accomplished improvisers (10 women) configured in different ensembles, to perform two dozen more songs from the book.

Neither an unorthodox instrumentation (two trombones, two guitars, acoustic piano, Korg synth organ, acoustic bass, trap drums) nor a boomy-yet-muddy mix could inhibit Next Jazz Legacy’s variegated, well-executed four-tune set (Emily Remler’s “Blues For Herb,” Nubya Garcia’s “The Message Continues,” Cassandra Wilson’s “Broken Dream” and Bria Skonberg’s “Villain Vanguard”). City Winery’s sound crew ignored the issue until Michele Rosewoman pointedly spoke up midway through set one of the main event before playing her “The Thrill Of Real Love” with a quintet. Rosewoman’s solo was muffled, but Veronica Leahy’s swooping soprano solo and Tia Fuller’s stentorian alto declamation were not. The sound was crisper by set’s end, when Rosewoman played Melba Liston’s Monkish ballad “Just Waiting,” after Angelica Sanchez and Helen Sung had performed “Quick Tipper“ and “Chaos Theory” in trio with superb “Next Jazz Legacy” drummer Ivanna Cuesta-Gonzalez and stalwart bassist Rahsaan Carter.

There followed singers Michael Mayo, Sara Serpa and Devon Gates, backed by pianist Julius Rodriguez, Carter and drummer Tcheser Holmes. Perhaps influenced by esperanza spalding, Gates, who’d played bass with authority and charismatic joie de vivre throughout the Next Jazz Legacy portion, constructed a stirring, stately bass line to complement her voice on “Don’t Wait.” Serpa’s pellucid soprano animated her Brazil-inflected “Primavera,” Mayo nailed Gretchen Parlato’s “Circling” with aplomb and grace; Gates joined him for an ebullient version of Abbey Lincoln’s classic “Throw It Away”; the three singers raised a joyful noise on Luciana Souza’s “At The Fair.”

An “alto madness” segment followed with Fuller, Leahy and Caroline Davis, propelled by Sung, Gates and Holmes. Each projected their individualism on “Spank,” a post-Tony Williams line by Cindy Blackman, then split off to play originals. After a sizzling Fuller-Holmes duo on “Queen Intuition,” Leahy and Angelica Sanchez joined the fray with Leahy’s gradually ascendant “20/20,” which highlighted the composer’s harmonic erudition and impeccable soprano sax intonation. Davis further upped the ante with the Coltrane-esque “Kowtow,” incrementally ratcheting the intensity to celestial heights with circular breathing and keening tone. The three altos reconvened to tackle Patrice Rushen’s burner “Shortie’s Portion” — Fuller ferociously swinging, Davis Birdlike, Leahy dancing through the changes.

Time was short for the final group: Carrington (who’d spent much of the evening playing with Jen Shyu at another venue) with pianist Kris Davis, bassist Linda Oh and guitarist Mary Halvorson (playing with Carrington and Oh for the first time). With efficient, unflappable creativity, they presented Marilyn Crispell’s “Rounds,” Davis’ “Sympodial Sunflower,” Halvorson’s “Heartdrop,” Oh’s “Ten Minutes To Closing” and Carrington’s “Samsara (For Wayne).”

Two nights later, the Jazz Gallery hosted the second of a two-concert showcase for Kris Davis’ Pyroclastic label (night one had the WKF imprimatur). The proceedings manifested everything that jazz can be circa 2023. Bass maestro Eric Revis led off with a resourceful quintet (Bill McHenry, tenor; Darius Jones, alto; Davis, piano; Chad Taylor, drums) well suited to interpret five “Mingus with a twist” tunes culled from several of his past recordings. The evening ended with the brilliant percussionist Patricia Brennan interacting with a world-class unit (Kim Cass, bass; Marcus Gilmore, drums; Mauricio Herrera, congas and batá), whose five rhythmically thrilling compositions seemed to piggyback off ideas refracted from ’60s innovators Walt Dickerson and Bobby Hutcherson — she deployed the vibraphone through various electronic filters to create otherworldly shapes and tones within the flow. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…