Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

In Memoriam: Jack DeJohnette, 1942–2025

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

Stefon Harris’ latest album, Sonic Creed, includes a number of original compositions, as well as “Now,” a track written by vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson.

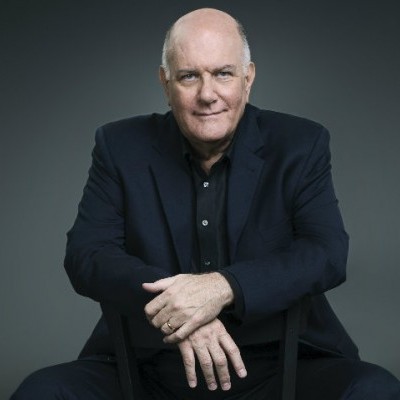

(Photo: Jimmy & Dena Katz)Quick of mind and compact of body, Stefon Harris moved easily from the vibraphone to the computer to the electric keyboard in the studio of his New Jersey home. Loquacious by nature, he maintained a steady stream of talk along the way.

But for someone known as patient under pressure—on the bandstand, in the boardroom or at the podium—his delivery was uncharacteristically urgent. The August day was waning, and he had an improbable story to tell.

Up from hardscrabble origins in Albany, New York—where he was too poor even to own an instrument—he has, at age 45, parlayed multiple gifts and considerable grit into positions of distinction. In the process, he has begun to shape a legacy as the personification of the modern artist/educator/entrepreneur.

Harris topped the Vibraphone category in the DownBeat Critics Poll this year and last. With the retirement of Gary Burton in 2017 and the death of Bobby Hutcherson (1941–2016), Harris has emerged as perhaps the most renowned practitioner of the instrument. But he yearns for something much deeper than fame.

“When I think about the end of my time on this planet,” he said, “I want to be able to look back and say I did something I could be proud of. It’s not an aspiration of mine to look back and say, ‘I was the greatest vibraphonist in history.’ My ultimate ambition is to help the world understand the value of empathy.”

By all accounts, the strands of his narrative—leveraging his clout as associate dean and director of jazz arts at the Manhattan School of Music to connect the school with its Harlem environs, developing an ear-training app to bring jazz education to a wider audience and creating presentations that convey the jazz sensibility to the corporate world—support that lofty ambition.

So, too, does his new album, Sonic Creed (Motéma). Out Sept. 28, the album, the third with Harris’ group Blackout, pays homage to African American artists on a personal level, while placing them in a larger context. “There’s nothing on Sonic Creed that isn’t directly from my life experience,” he said. “This album is about celebrating and amplifying the values of black culture and art.”

At the center of the project are Blackout’s core members: James Francies on piano, Joshua Crumbly on bass and two mainstays—saxophonist Casey Benjamin and drummer Terreon Gully—who appeared on the band’s previous albums, 2004’s Evolution (Blue Note) and 2009’s Urbanus (Concord). Those efforts represented departures from Harris’ other, more orchestrated ensembles.

“He had charts, but they were to be loosely interpreted,” Benjamin said. “I don’t think any of us knew what shape the band would take on.”

Blackout has taken on a free and open shape, its palette incorporating colors and textures from outside the jazz mainstream—Benjamin is known for his vocoder, as well as his saxophones, Gully for his forays into gospel, r&b and reggae—even as it draws on jazz standards. The artists’ dedication to this approach is evident throughout the new album.

“It’s the right confluence of spirits who have the same vision,” Harris said.

That vision is clear from Sonic Creed’s opening track, “Dat Dere.” Written by Bobby Timmons and popularized by Art Blakey on 1960’s The Big Beat, the tune’s presence on the album shines a light on the teaching of jazz—and the status of Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in that endeavor—before it became institutionalized in the academy.

“As an educator, a dean in a position of influence, I wanted to be able to herald Art Blakey as one of the founding fathers of jazz education,” Harris said.

Following “Dat Dere,” the album focuses on the values of family and community with two Harris originals. “Chasin’ Kendall”—dedicated to Harris’ two sons, whose middle names are Chase and Kendall—recalls the summer days of Harris’ youth, built as it is around a bass line like those that anchored the easygoing Motown hits that filled the air.

“I was wondering how you make a piece of music that captures that spirit,” he said, adding that it wasn’t until the days leading up to the April 2017 recording session that he came up with the defining bass line while picking at the piano.

“Let’s Take A Trip To The Sky,” meanwhile, is a sensuous setting of a poem Harris wrote for his wife while he was on the road. The piece, intended as a 10th anniversary gift, takes flight on the wings of Jean Baylor’s soaring vocals, backed by Benjamin’s spare vocoder and Harris’ luminous harmonies—each chord a sonorous evocation of a specific emotion.

The album then circles back to classics, with animated versions of Horace Silver’s “The Cape Verdean Blues” and Wayne Shorter’s “Go,” which Harris arranged for the SFJAZZ Collective a decade ago. Shorter’s ability to build community is something of a model for Harris, who recalled sharing a transcendent moment onstage with the saxophonist in 2014.

Jack DeJohnette boasted a musical resume that was as long as it was fearsome.

Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

D’Angelo achieved commercial and critical success experimenting with a fusion of jazz, funk, soul, R&B and hip-hop.

Oct 14, 2025 1:47 PM

D’Angelo, a Grammy-winning R&B and neo-soul singer, guitarist and pianist who exerted a profound influence on 21st…

Kandace Springs channeled Shirley Horn’s deliberate phrasing and sublime self-accompaniment during her set at this year’s Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival.

Sep 30, 2025 12:28 PM

Janis Burley, the Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival’s founder and artistic director, did not, as might be…

Jim McNeely’s singular body of work had a profound and lasting influence on many of today’s top jazz composers in the U.S. and in Europe.

Oct 7, 2025 3:40 PM

Pianist Jim McNeely, one of the most distinguished large ensemble jazz composers of his generation, died Sept. 26 at…

Drummond was cherished by generations of mainstream jazz listeners and bandleaders for his authoritative tonal presence, a defining quality of his style most apparent when he played his instrument unamplified.

Nov 4, 2025 11:39 AM

Ray Drummond, a first-call bassist who appeared on hundreds of albums as a sideman for some of the top names in jazz…