Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

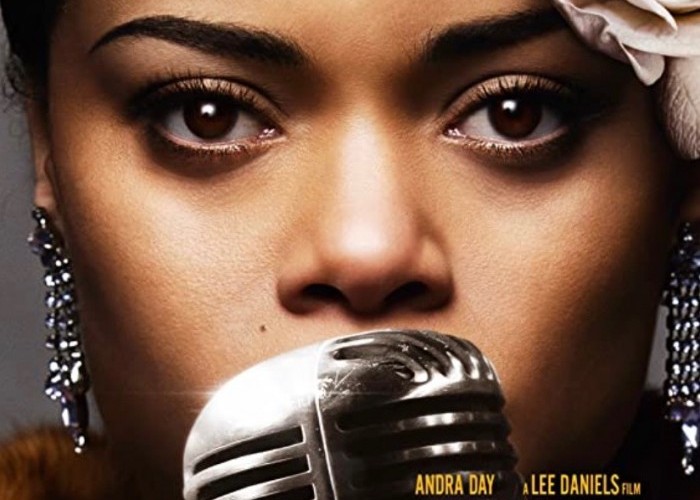

Andra Day portrays Billie Holiday in The United States vs. Billie Holiday.

(Photo: Photo Courtesy of Hulu)Director Lee Daniels has taken Johann Hari’s drug war history, Chasing the Scream, mixed it with Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, shaken vigorously and concocted The United States vs. Billie Holiday, a political cocktail both epic and evil that premiered on Hulu. It will be compared to Lady Sings the Blues (1972), in which Diana Ross played Holiday in a familiar love story of public triumph concealing private pain. It remains an achievement due to the gangly eloquence of Ross’ Oscar-nominated performance. But it was also a movie of its time. Its message was drug use is a malignancy that needs to be fought. Fifty years later, the battlefields of the drug wars that followed are scorched with corruption, failure and huge prison populations.

So Daniels tells a story that could not be told in 1972. The malignancy is not drug use but the politics of the drug wars themselves. Daniels and screen writer Suzan-Lori Parks personify this in the racist monster that is Harry Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics from 1930 to 1962. As interpreted by Garrett Hedlund, he plays Inspector Javert to Billie Holiday’s Jean Valjean, projecting a quiet fanaticism with a mission to pursue and destroy everything Holiday represents.

What she represents is summarized in the anti-lynching song “Strange Fruit.” Like the pieces of bread that ignited Javert’s quest in Les Miserables, “Strange Fruit” becomes the original sin of Anslinger’s pursuit. But “you can’t arrest someone for a song,” someone protests. “No,” he says, “but you can for drugs.” So drugs become incidental, a means to his end. It’s the song he’s really after. As for Holiday, she is a profane and profoundly damaged woman by the time the story starts in 1947. But as played by Andra Day in her debut film performance, she finds in the song an unexpected inner strength to resist Anslinger’s depraved tenacity.

Until recently, jazz history has been silent on Anslinger. He received attention in Martin Torgoff’s 2016 book Bop Apocalypse (see DownBeat April 2017), and by most accounts he was an unrepentant racist. Daniels takes it from there. He enriches his depravity with flourishes of fictional license here and there. In a 1947 meeting we see him plotting with a cabal of political rouges that includes John Stennis, Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn. Aside from being impossible (Cohn hadn’t passed his bar exam yet and wouldn’t meet McCarthy until 1953), it’s unnecessary. Why tie him to such associates when he says things like, “Drugs and niggers are a contamination on our great American civilization. This jazz music is the devil’s work and this Holiday woman has got to be stopped.” Even McCarthy and Cohn might have walked out on that meeting.

As for his obsession with “Strange Fruit,” that’s harder to gauge. In the ’40s it was neither popular nor widely performed outside the left-wing folk circuit. Holiday introduced the song before the war, but never sang it on radio or in a movie, only before club and theater audiences. The record was for a tiny jazz label. Its later status as Time Magazine’s “song of the century” didn’t take root in popular culture until after Holiday’s death. So it’s hard to understand Anslinger’s paranoia over an obscure cult song that never got near the Hit Parade.

Perhaps Holiday herself planted the film’s central conceit in a DownBeat interview she gave on June 4, 1947. “I’ve made a lot of enemies,” she told the journalist Mike Levin. “Singing that ‘Strange Fruit’ hasn’t helped any, you know. I was doing it at the Earle (Philadelphia) ’til they made me stop.” According to the movie, on May 27, 1947, the Earle is raided by a phalanx of cops who literally assault the stage as Anslinger watches with satisfaction from the rear. Daniels’ precision on dates, however, is sometimes just an illusion of accuracy. The Earle gig ended on May 16. On May 27 she was actually sentenced in a Philadelphia court for an earlier offense. And as far as Anslinger personally presiding over Holiday’s arrests… well, it’s only a movie.

But he did create a Stasi-like network of African-American agents who infiltrated and gathered evidence inside the Black drug networks. The most prominent among them was Jimmy Fletcher, a privileged, educated man with connections where they counted. Compared to the procession of bullies and misogynists Holiday favored, he was the best man in her life. Trevante Rhodes plays him with cool a confidence that drugs are a genuine curse on his people. He commits to the cause, gains Holiday’s trust, sets her up for a bust, then falls in love with her. At the crucial moment, he puts duty before love. But as he learns more about her history, he becomes conflicted, especially when he recognizes his boss’s motives. Ultimately, he deliberately botches a 1949 case against Holiday and breaks with the Bureau. In the movie, he regains her trust and the relationship continues to the end, but, again, this is fiction.

The film is structured in flashbacks, opening with a 1957 radio interview, then jumping back to Café Society in 1947, then forward to her death 12 years later. Neither Café Society nor Lester Young, who hovers as a perpetual sideman, had anything to do with Billie during this period and don’t belong in the picture. But in broad strokes, events covered after 1947 are true enough. More important, Andra Day’s gritty, unsentimental performance catches Holiday’s defiant recklessness without inviting pity or excuses. She owns her mistakes. It will be an awards magnet when the time comes. Moreover, the film looks true to its time with a softly aged Kodachrome glow. Daniels has crafted some gorgeous process shots, too. Watch Billie walk across Times Square in the rain circa 1950. It’s suitable for framing.

Great talents who court their own doom with such fervor are forever fascinating to us. But they are beyond our understanding, which is why every generation sees a piece of itself in Holiday’s story and seeks fresh perspectives in understanding it. The United States vs. Billie Holiday finds a newly relevant dimension to explore. But in a story with no happy ending, final answers to its more existential issues remain elusive. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…