Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

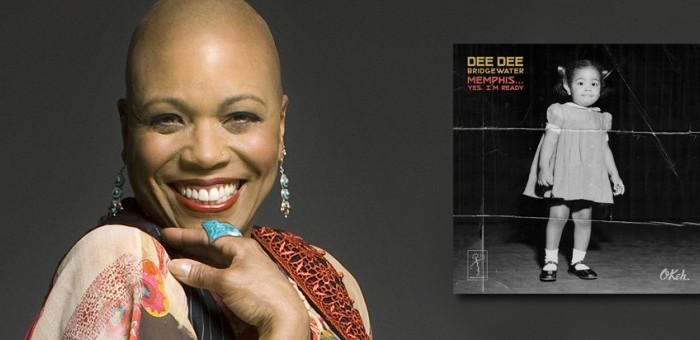

Dee Dee Bridgewater will release Memphis—- Yes, I’m Ready on DDB/OKeh Records on Sept. 15.

(Photo: Courtesy OKeh Records. )Dee Dee Bridgewater’s 2007 disc, Red Earth—A Malian Journey (Verve), found her searching for her African roots. Her new disc, Memphis … Yes, I’m Ready (DDB/OKeh Records), sees her tracing her personal roots on closer ground. Although the three-time Grammy winning singer and Tony Award-winning actress was born in Memphis, she left the Bluff City before she reached age 5, when her family moved to Flint, Michigan. Still, the blues and soul music endemic to that city left lasting impressions on Bridgewater, as did other cultural touchstones.

On Memphis, Bridgewater recruited saxophonist and Memphis-native Kirk Whalum as co-producer. The two corralled a supreme team of musicians from the city, including organist Charles Hodges (who played on many Hi Records hits by Al Green, Ann Peebles and others); trumpeter Mark Franklin (who played with Gregg Allman); keyboardist John Stodddart; guitarist Garry Goin; and drummer James Sexton. Together, they explore such gems as B.B. King’s “The Thrill Is Gone,” Otis Redding’s “Try A Little Tenderness,” Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog” and Peebles’ “I Can’t Stand The Rain,” resulting in a poignant and personal diary of self-discovery.

Bridgewater talked to DownBeat about the inspiration behind Memphis and how her frequent visits there awaken certain childhood memories. She also shared some of her fears about releasing an r&b disc after establishing bona fides as a jazz artist.

Will this album be a big surprise to your longtime fans?

I’ve dedicated most of my adult career to jazz and trying to keep vocal jazz traditions going. I’ve just been jazz, jazz, jazz. Also, this year, I got the 2017 NEA Jazz Masters [Award]. Then I come out with a soul album, which made for great timing. (Laughs)

But I do know that this music is an extension of jazz; it’s part of the evolution of black music in America. After the blues and jazz, we had soul and r&b music.

Making this album sort of coincided with my personal search for who I am, why I am a certain way, why I like to do the things certain ways, and other stuff like, “Why do I always feel so comfortable when I’m in the South.” So Memphis was like an offshoot of starting that research, which really began around 2014. That was the first time I went back to Memphis.

This album contains music that I listened to as a teenager on WDIA—which is the first radio program in the U.S. that was programmed entirely for the African American community. Rufus Thomas used to DJ there. My daddy was a DJ, too, along with Rufus and B.B. King. My father’s name is Matthew Garrett and they called him “Matt, the Platter Cat.”

Did you face any challenges covering this material after years of singing jazz.

Doing these songs—they have simple melodies and arrangements—and being a jazz singer, I’m already starting to think, “Oh, I’m going to have to change some of this shit up, because I’ll get bored in a minute.” Just from a music-challenging point of view, this is not challenging music.

This is feel-good music. And it’s music that I’ve chosen to do at this point in my life because I need to feel good. I recently lost my mother; she was dying. Then I lost my dog on December 1. Then I had two really bad physical accidents.

I’ve had a lot of major trauma in the last six months. So I needed to do Memphis for me. I don’t know how long this exploration into soul music will last. I think it’ll somewhat depend upon the reaction from the public after the album comes out. But I do feel some kind of creative energy from Memphis every time I go there. So I’m going to try to drive up there [from my home in New Orleans] often to see what that is. I don’t know if it means that I will eventually move there. But I do feel very much at home there.

I’m also that singer that never thought that I sounded black enough in terms of my phrasing. Maybe I can if I practice it, but I’m not one of those singers who can sing all that [melismatic] stuff. I can’t do that shit. It’s not me.

I’ll be honest. When we were in the studio, laying down the first track—[my daughter] Tulani was there with me—I said, “Tulani, I’m not sure if I’m going to be able to do this.” She said, “Just go in there and sing.” I think the first song we did was “I’m Going Down Slow.” I remember coming out of the studio, listening to it, then saying, “That’s me?” I was thinking, “Boy, this sounds good. This sounds relaxed. It feels right.” So recording it wasn’t contrived at all.

Memphis is just another part of me. The music here is just as real as my scatting.

Some of your rasp in your voice on Memphis is reminiscent of Tina Turner. Was she an influence on you?

I heard that too! I love Tina Turner. Are you kidding? Shoot, yeah! I love me some Tina!

Do you still have family in Memphis??

I really don’t have family in Memphis. My mom is from Flint, Michigan. So when my parents decided to move north, they moved to Flint because that brought more opportunities in the factories and a better school system. So that’s why we moved there. All of my family on my mother’s side is from around the Flint area.

My father was born in Newport, Kentucky. His family had moved to Cincinnati when he was a little boy. So for all intents and purposes, my daddy’s family is from Cincinnati and Kentucky. So I don’t really have any real family in Memphis.

I was born in Memphis. During the first three-and-half years of my life, I was in Memphis. So that’s how I got that Memphis DNA. But I think I was there long enough that it made an impression on my mind and spirit. I remember at four years of age, my mother corrected my Southern accent. She said I had a heavy southern accent. The last word I wouldn’t let go off was “Minfus.” When people asked where I was from, I would say, “Minfus” instead of Memphis. (Laughs).

So what came up during this personal research back in Memphis?

Going back, a lot of things came up for me. It explained the food that I like. My mother obviously learned how to cook in Memphis. There’s a soul food restaurant that Martin Luther King Jr. loved that has returned, called the Four Way. I don’t know who’s in that kitchen but my mom cooked just like these people. Every time I go to Memphis, that’s where you’ll find me—getting my chitlins, my smothered cabbage, my pork chop—all of that.

I stopped at this joint down on Main Street called Sam’s Hamburgers and More. That hamburger tasted like my mama’s hamburger—the seasoning, everything! I went to have lunch at the Madison Hotel with Kirk, and we had ordered chicken noodle soup. Honey, they brought out chicken and dumplings. I tasted it then said, “Oh my God!” I told Kirk, “This is my mama’s chicken and dumpling.”

So all of that sort of answered my questions. Now, when I go to Memphis, I’ll drive in some neighborhoods and will get a shock or a flashback about something that happened to me in particular neighborhoods. I think we lived mostly in south Memphis, which is where most of the black community was.

How did you cull the music for Memphis … Yes, I’m Ready?

These are just songs that I loved. There’s no deep, dark thing associated with the song choices. (Laughs) These are just songs that I love and that I listened to on WDIA.

Considering that your early LPs from the mid-’70s and early ’80s were more jazz-funk and r&b, do you ever think about revisiting that material?

Nope. (Laughs) When Theo Croker’s band was my band, we did “Maybe Today” from my [1978] Just Family album, “Time And Space” from my work with Roy Ayers, and “Love From The Sun” from my work with Norman Connors. So we touched upon some of my old stuff because Theo and the guys like that music. But I’m not that interested in that stuff.

I would like to do some songwriting in Memphis, because when I go to Memphis there’s such an inexplicable comfort that I feel. I’m going to start working on some new material out there. I don’t know if it’ll have any inklings of jazz.

This album marks another watershed moment in your career. Talk about some of your fear surrounding the release of Memphis.

What I don’t want to happen is for someone to listen to Memphis then say, “Why is a jazz singer trying to do this kind of music?”

But it’s surprising me that I feel concerned about how other people feel about me singing soul and blues with Memphis. I want people to like it. I’m concerned that the jazz constituent will not like it.

Now, why does that mean so much to me? I don’t know. I keep asking people, “Are you sure you like it?” I’ve never, ever done that before. I’ve never felt a need to justify anything that I’ve done before. And I know that it’s within my rights to do this album as a human being and as an artist. Yet again, I’m just staying true to myself.

It just really interesting that I get real insecure when I do a show with this at a serious jazz festival or venue, because I haven’t had a lot of crossover yet in other genres of music.

For the last 10 years, my main purpose has been going out on tour to make money so that I could take care of my mother in assisted living at a good enough facility in which I didn’t have to worry that much about her care when I went out on the road.

Maybe I feel like an opened wound because I’m still mourning the passing of my mother. Also, this is the kind of music that mother did not want me to do. She did not want me to sing blues. She made me promise when I started singing to not sing the blues. I whispered, “I promise.” (Laughs) So I was kind of selfish when I did this album, thinking, “My mother would die if she heard me doing this record,” because I loved my mama. She raised me right. Everything that I did had my mother in mind. This is the first year that I’m motherless. So I’m trying to fix that empty void. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…