Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

In Memoriam: Jack DeJohnette, 1942–2025

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

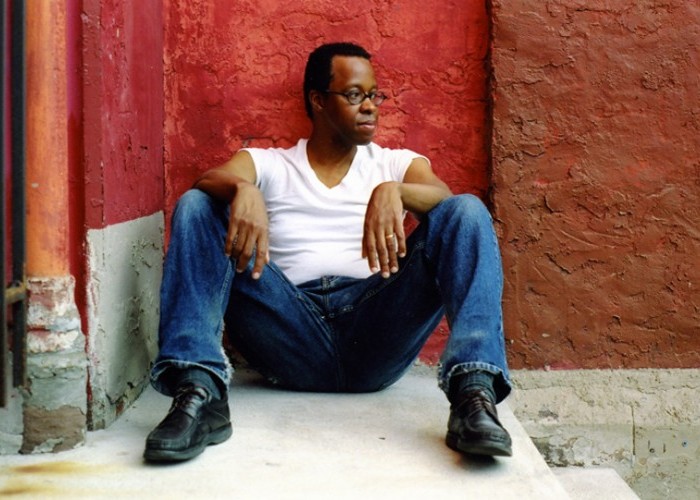

In 2018, pianist Matthew Shipp has issued a pair of albums on ESP-Disk, as well as a three-album set alongside saxophonist Ivo Perelman and a live recording with bassist William Parker.

(Photo: Courtesy of the Artist)Pianist Matthew Shipp has opened 2018 with a pair of new albums that mark his debut as a leader on ESP-Disk, where he joins the likes of Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Lowell Davidson and Ran Blake in the historic imprint’s longstanding efforts to champion creative music.

The first title, Zero, is the musical extension of a scientific dissertation he gave at The Stone last year, exploring the number and its varying degrees of meaning across 11 compositions for solo piano. The other LP, Sonic Fiction, is a free-flowing quartet recording that reunites Shipp with longtime drummer Whit Dickey, bassist Michael Bisio and Mat Walerian, a fiery young saxophonist from Poland who once took lessons from the bandleader.

The politically active icon of New York’s underground jazz scene took some time to discuss those aforementioned albums, as well as Oneness, a new three-disc collection with Ivo Perelman, and Seraphic Light: Live At Tufts University, which finds him in collaboration with saxophonist Daniel Carter and bassist William Parker.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re very active politically online, but you’ve mentioned that you keep it separate from your music, correct?

I don’t want Donald Trump anywhere near my music. The consciousness of that does not belong anywhere in anything I do with a musical instrument.

Thinking about how heavy jazz was in the late ’60s, some of the emotions about the socio-political climate of the time might have had bearing on the direction performers like Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp and Albert Ayler were going.

Well, the ’60s were a really special time. It was a volcano, just a vortex of energy and social situations. I believe that Coltrane was centered in music, and the cosmic dimensions of what he was trying to do with sound were inherently rooted in that. But when you are doing art in a period which is that socially pregnant, there can’t help but be parallels.

In Archie Shepp’s case, I’m sure there was some Marxist ideology. I mean, I know there is—and that goes along with the music. But at the end of the day, music is about the note; it is abstract. So, unless you’re putting lyrics to something, it’s a whole different thought process. Now, somebody can program their subconscious mind with images that have some type of discursive meaning to them that applies to a socialist thing. But I think every musician is different. I would tend to think that Ayler—and Ayler was, you know, crazy—but because of that craziness there was a real purity to the music, as opposed to trying to superimpose a social structure over it. But things were going on at the time and musicians were aware of them, and someone like Archie Shepp may have had more of an overt political agenda in the music than Ayler.

It must be an exciting notion to be on the same record label that Ayler once recorded for.

Well, I’m such a big Albert Ayler fan, so Spiritual Unity has been a seminal album for me. But I also love Paul Bley’s ESP albums and some of the Sun Ra stuff. I’ve always been an ESP fan, but I was also friends with Bernard [Stollman] for years, though I was never really asked to record with them as a leader until now. But then when Bernard died, the guy who took over the label, Steve Holtje, is a really close friend of mine and invited to me record for them. It seemed like the right move.

How does Mat Walerian rank among the saxophone players you’ve worked with during the past 30 years?

When you consider the guys I’ve worked with, it’s really fascinating to bring a young person in like this and play with somebody who is from a whole different generation. It’s a different thing from playing with my peers, definitely.

What inspired you to name the new quartet album Sonic Fiction?

I actually don’t know why I titled this album Sonic Fiction. I was searching for a title and I was thinking, “Yeah, there’s a sort of narrative to this album, and all music on one level is a piece of fiction.” It’s also reality, because it is what it is. But it’s an alternative reality as well. And it’s sonic. It’s actually a pretty literal title, come to think of it.

The concept of your solo album Zero is interesting, especially when you take in the recording of your “lecture on nothingness” from The Stone that’s on the second disc.

I’m into a lot of mysticism, so I’m always kind of obsessed about where these things come from. For instance, if you believe in the Big Bang, before space and time, everything was coming out of nothingness. I’m obsessed with where these things come from, where is the matrix? What is it? There’s some type of ground state that’s not even a one. It’s zero. Yet, everything comes out of it. And that’s an idea that really intrigues me.

On the other side of the coin, there’s the exploration of oneness on your latest work with Ivo Perelman.

Oneness is the culmination of what Ivo and I have been working on for years. The duo is the central project for us—and we feed off each other’s energy and intellect and spirit. It is a project we both take very seriously.

It seems like 2018 is going to be a super productive year for you. What’s behind all this activity?

I’m in a period of reflection on my whole past. And as far as moving ahead into the future, I’m going to just continue to refine my personality as a pianist. I do feel like I’ve done a major body of work in my life and I’m trying not to repeat myself. But I’m really trying to concentrate on the personality of my trio and my solo material, especially what I’m doing with Ivo. That’s where the focus is, and I’d like to age with grace in the way that Ahmad Jamal has; that’s a goal of mine. If I could do that, I’d be very happy. DB

Jack DeJohnette boasted a musical resume that was as long as it was fearsome.

Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

D’Angelo achieved commercial and critical success experimenting with a fusion of jazz, funk, soul, R&B and hip-hop.

Oct 14, 2025 1:47 PM

D’Angelo, a Grammy-winning R&B and neo-soul singer, guitarist and pianist who exerted a profound influence on 21st…

Kandace Springs channeled Shirley Horn’s deliberate phrasing and sublime self-accompaniment during her set at this year’s Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival.

Sep 30, 2025 12:28 PM

Janis Burley, the Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival’s founder and artistic director, did not, as might be…

Jim McNeely’s singular body of work had a profound and lasting influence on many of today’s top jazz composers in the U.S. and in Europe.

Oct 7, 2025 3:40 PM

Pianist Jim McNeely, one of the most distinguished large ensemble jazz composers of his generation, died Sept. 26 at…

Drummond was cherished by generations of mainstream jazz listeners and bandleaders for his authoritative tonal presence, a defining quality of his style most apparent when he played his instrument unamplified.

Nov 4, 2025 11:39 AM

Ray Drummond, a first-call bassist who appeared on hundreds of albums as a sideman for some of the top names in jazz…