Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

In Memoriam: Ken Peplowski, 1959–2026

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

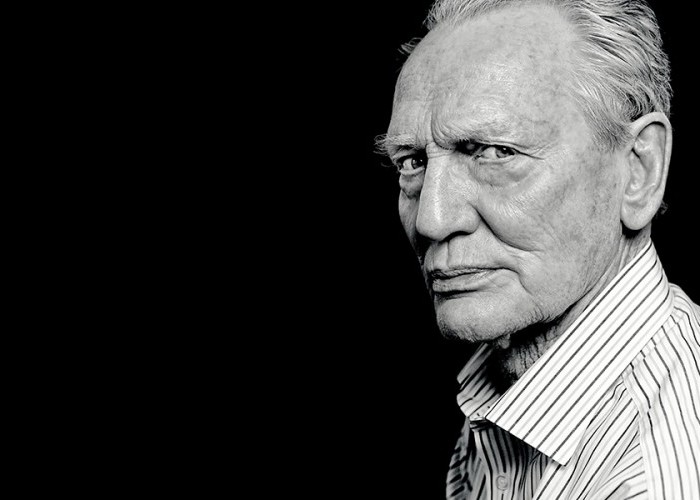

Ginger Baker (1939–2019)

(Photo: Courtesy Motéma)Following a serious illness, drummer Ginger Baker has died in Britain. On Oct. 6, his family issued a statement on Twitter: “We are very sad to say that Ginger has passed away peacefully in hospital this morning.” He was 80.

On Sept. 25, the family had announced that Baker was critically ill and had been hospitalized.

Baker was a member of rock trio Cream alongside guitarist Eric Clapton and bassist Jack Bruce (1943–2014). The band’s classic tracks include “Sunshine Of Your Love,” “I Feel Free,” “White Room” and the instrumental “Toad,” featuring Baker’s powerful drum solo.

Baker played drums on many songs that are now staples of classic rock radio, including “Can’t Find My Way Home,” a Blind Faith number featuring Steve Winwood’s lead vocals.

During the course of his lengthy career, Baker was a member of several bands besides Cream and Blind Faith, including the Graham Bond Organisation, Ginger Baker’s Air Force and the Baker Gurvitz Army. His collaborators included singer Fela Kuti, guitarist Bill Frisell, bassist Charlie Haden, trumpeter Ron Miles, the band Public Image Ltd. and many others.

Paul McCartney posted a tribute on Twitter, describing Baker as a “great drummer, wild and lovely guy.” He wrote: “Sad to hear that he died but the memories never will.”

Ringo Starr’s Twitter tribute referred to Baker as an “incredible musician” who was “wild and inventive.”

Baker’s accolades included induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1993 as a member of Cream.

Known for being a dynamic musician with a gruff personality and a hot temper, Baker was the subject of Jay Bulger’s 2012 documentary Beware Mr. Baker.

On June 24, 2014, the Motéma label issued Baker’s jazz-rock album titled Why?, which was his first studio effort in 16 years. He recorded it with his quartet Jazz Confusion. Later that year, DownBeat posted an interview with Baker, which is presented below. The piece was written by the late drummer and journalist Robin Tolleson.

(The following article was originally posted in 2014.)

Ginger Baker Returns

Two patrons at Ginger Baker’s sold-out Ronnie Scott’s show in July were grumbling about the music not being “jazz.”

Perhaps the London patrons had forgotten whom they had come to see. More certainly, they were missing the point of the drummer’s current band, dubbed Ginger Baker’s Jazz Confusion.

Baker—who achieved global fame in the ’60s with power trio Cream, alongside guitarist Eric Clapton and bassist Jack Bruce—would agree with those two patrons’ assessment. “It’s not jazz … it’s music,” Baker says. “You can’t put the music in boxes, in my opinion.” The project does, powerfully, combine the drummer’s two favorite kinds of music: jazz and African styles.

The Jazz Confusion features tenor saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis, a craftsman equal parts Maceo Parker and John Coltrane. It also includes melodic and dynamic bassist Alec Dankworth, the son of royal couple John Dankworth and Cleo Laine. And it centers around the interplay of Baker and Ghanian percussionist Abass Dodoo.

The band doesn’t play much traditional swing. However, as Baker says, “Everything we do swings. Hello? It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got it, does it?”

The quartet’s album, Why? (Motéma), includes original material as well as a version of Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints.” The title track, a Baker original, has a Jamaican dancehall flavor, and the songs “Cyril Davis” and “Aiko Biaye” are in 12/8. “We play 12/8,” Baker explains. “1-2-3, 2-2-3, 3-2-3, 4. It’s just a natural time. All jazz music, in fact, if you were to write it correctly, is in 12/8. Blues music is in 12/8.”

When the Jazz Confusion plays a standard like Sonny Rollins’ “St. Thomas,” not one note is taken for granted. “It just happens,” Baker laughs. “We never actually rehearse it. It’s a song we all know and we can all play, so we have fun with it. Everything’s different every night. It’s never the same twice. That’s how we play.”

The band’s arrangement of “Footprints” lends itself to a particularly melodic drum solo from Baker. “You’ve got to play a song. You’ve got to improvise something that’s musical,” he says.

Baker recalls an encounter he once had with drummer Philly Joe Jones. “I did a thing on television in England about 1970 when Philly Joe was in town, and I happened to meet him. He’d seen this thing, and he said, ‘Yeah, man, you tell a real good story when you’re playing the drums.’ He dug it, because it was a complete piece, a piece of music, not just a series of things that are difficult to do joined onto each other.”

Baker met Dodoo seven years ago at an event presented by the Zildjian cymbal company. “We played together and it was great,” Baker says. “Then I was talking to him, and found out he’s the nephew of a drummer that I worked with in the ’80s [J.C. Commodore].

“Everything that I’ve done since that Zildjian gig, I’ve played with Abass. He’s a very good friend of mine, as well as being a really fantastic drummer.”

At Ronnie Scott’s, Baker referred to Dodoo as his “right hand.” “We think on the same wavelength, so we just play together,” Baker says. “It’s very easy to play with him.” The number of sounds they get from the two drum kits, percussion and numerous splash cymbals is amazing, and the grooves go deep.

It was Baker’s longtime roadie, Hagar, who suggested that former James Brown saxman Ellis—a masterful player who can say a lot in a few notes—be in the new group. “Then he brought Alec along to rehearsal as well, and it just worked, so that was it,” the drummer recalls.

Twice during the evening at Ronnie Scott’s, Baker had to hurriedly leave the stage. When he returned the first time, he growled into the microphone, “Old age. When I get it coming I’ve got to go.” Ever the rock star, Baker returned from a second-set bathroom visit zipping up his trousers as he emerged from backstage.

Following a spirited “Aiko Biaye,” with Baker dealing out one inventive, powerful rhythmic idea after another in tandem with Dodoo, the 74-year-old drummer quipped, “Really and truly, I’m getting too old for this playing.” But at least for now, the spirit is willing and the flesh will not give up.

“Yeah, I’m still playing good,” he says with a grin. —Robin Tolleson

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…