Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

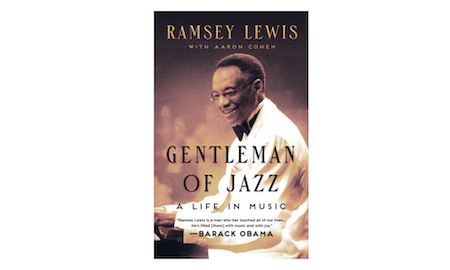

“I’m not going to be around forever and ever,” Ramsey Lewis told his co-author Aaron Cohen as they were planning the pianist’s memoir. “I would like something left behind that tells my story.” Those words carried unforseeable prescience, for Lewis, 87, died peacefully of natural causes on Sept. 12, 2022, at home in Chicago, leaving behind his wife, Jan, two daughters and three sons as well as an autobiography he would not live to see published.

Known for being an effective communicator of jazz as much as a performer of it, Lewis’ final words resound off the page with his trademark clarity and warmth in Gentleman of Jazz. He details his life’s journey from a young boy in the Cabrini Homes housing projects on Chicago’s North side — one who was fascinated both by classical piano and gospel music — to becoming a talented jazz pianist who successfully crossed over into the burgeoning soul-funk scene in the late ’60s and ’70s. Lewis emerged as an important ambassador of jazz to the general public as a radio and television host, becoming a beloved musical icon in the Windy City.

Lewis’ 1956 debut recording at age 21, Ramsey Lewis And His Gentle-Men Of Swing (Argo), was released the same year as Duke Ellington At Newport, The Unique Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins’ Tenor Madness and Clifford Brown And Max Roach At Basin Street. Nine years later in 1965, when Lewis released his breakout single “The In Crowd” from the live album of the same name, other current albums included Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage, Horace Silver’s Song For My Father, Wayne Shorter’s Juju and John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. And yet, it was Lewis’ trio that produced one of the most popular hits of the year when “The In Crowd” spent six weeks in the top 10 of the Billboard pop charts. Therein begat a fundamental conundrum that would dog Lewis’ entire career. Despite his undeniable popular and commercial success, he was rarely considered alongside the hallowed names in jazz such as those he is mentioned with in the same sentences above.

Lewis, who early in his career played with Roach, Sonny Stitt, Hank Mobley and Kenny Dorham, among others, alludes to his placement outside the in-crowd of jazz only obliquely in his memoir. For the most part, he chooses not to rebut his critics head-on, focusing instead on the many accomplishments he had achieved throughout his life and career.

He details encounters with brothers Leonard and Phil Chess, who signed the pianist to Argo, a subsidiary of their blues record label, Chess Records, and how they even manufactured a “rivalry” between him and their other big keyboard star, Ahmad Jamal, to generate buzz and controversy. He reminisces about gig life in and around Chicago, as when he and his trio were the intermission band at the famed London House for George Shearing or Oscar Peterson, or when after a road gig in Detroit, the Rev. C.L. Franklin invited them over to his house to meet his family and have one of his daughters, Aretha, sing and play piano for them.

Lewis lets his original drummer, Redd Holt, explain how — through the suggestion of a waitress Holt was flirting with — they decided to add “The In Crowd,” an R&B song by Dobie Gray they heard on the jukebox, to their set for the live recording they were about to do the next evening.

The overwhelming response catapulted the group, and they became one of the greatest keyboard-driven cover bands in history. Lewis converted into his own, funky style — from Chopin’s E minor Prelude to soul hits by Marvin Gaye and the Stylistics, to the White Album by the Beatles.

Lewis also outlines his relationship with Holt’s successor, Maurice White, then a young house drummer for Chess, whom Lewis coaxed out of his shell to learn to become an entertainer, an invaluable trait once White branched out to co-create Earth, Wind & Fire. Tracing Lewis’ discography through this time as he talks about his ongoing interactions with White and his superstar band provides a clear window into the close fraternity they had built and the particular sounds they produced as a result. “It’s questionable if there would be an Earth, Wind & Fire if it had not been for Maurice’s experiences with Ramsey Lewis,” Phillip Bailey, the lead singer for that iconic band, told Cohen.

In a recurring theme throughout the book, Lewis shares his feelings on how he felt as a Black man in America. He remembers as a kid watching a white man reprimand his grandfather, telling him, “Boy, why don’t you watch where you’re goin’?” Lewis said of the incident, “The way he looked at my grandfather and spoke to him broke my heart.” He remembers his piano teacher frankly admitting to his family that there were few opportunities for Black classical pianists, and that Lewis, even as talented as he was, had a better shot at a career in some other type of music. Elsewhere, he describes the disconnect between the color of his skin and his status as a musical celebrity:

When people say, “Oh, you’re the entertainer,” then that’s a different thing. But if you’re just a Black guy waiting to get in somewhere … you understand that you’re a Black guy. You don’t get the same privileges. “Why didn’t you tell me you’re Ramsey Lewis?” Why should I have to tell you?

Recollections like this help to explain Lewis’ dedication to the Black community in Chicago, including his early friendship with the Rev. Jesse Jackson, and his later support for a young lawmaker from his state who would eventually become a U.S. Senator and then President of the United States. Lewis channeled Obama’s message of hope into Proclamation Of Hope: A Symphonic Poem, an eight-movement suite for piano and a smaller orchestral ensemble in honor of the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth in 2009. That led to his culminating masterwork, “Concerto For Jazz Trio And Orchestra,” which he performed in 2015 for his 80th birthday with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

In the end, Ramsey Lewis’ story is one of transcendence, from a classical piano-loving kid from the housing projects to composing for and performing with symphonies, from jazz pianist to crossover pop-funk sensation, from “just a Black guy” to aiding the most powerful Black guy in the world, realizing himself as a beacon of hope to others. Just as they did when he uttered them on television or radio, the words Lewis left behind in his memoir will assuredly continue to educate and inspire as his music has.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…