Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Ron Carter’s recording with poet Danny Simmons, The Brown Beatnik Tomes (Live At BRIC House), is the bassist’s latest collaboration with someone from outside the world of jazz.

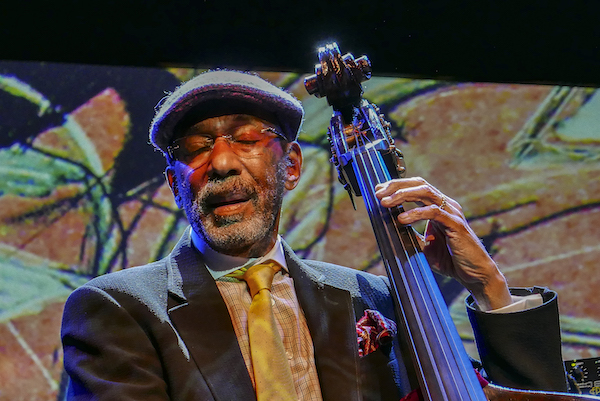

(Photo: Mark Lee Blackshear)When bassist and bandleader Ron Carter left the Blue Note stage on a recent night in lower Manhattan, a group of fans trailed behind him as he headed to the upstairs dressing rooms.

A line of autograph seekers with albums, books, programs and other memorabilia already had formed outside the door. Two or three were called in at time to bask in Carter’s presence, and he seemed to enjoy the adulation. Several of his admirers had copies of The Brown Beatnik Tomes (Live At BRIC House), the bassist’s recently released concert album recorded in 2015 with poet Danny Simmons. The disc’s title invokes the Beat Generation, and though Carter, 82, lived during that dynamic period of nonconformists, he said he didn’t participate, referring to it as mainly a movement of white guys.

The album, though, isn’t his first collaboration with someone from outside the jazz world. Carter scored and performed on the soundtrack to O Povo Organizado (The People Organized), a 1976 documentary by Robert Van Lierop about the successful revolutionary struggle in Mozambique.

The bassist added: “In the past, I had worked with poets, as well as folk singers, such as Leon Bibb. That was also at a time when LeRoi Jones was a popular poet and working with musicians. Danny Simmons came to me and asked if I would commit to [the project]. I didn’t know him, but I knew his brother [Def Jam founder Russell Simmons], and so it was on. I think, overall, we accomplished what we set out to do, and I hope it was a mutually rewarding experience.”

Simmons’ 2014 book, The Brown Beatnik Tomes—which features his writing and paintings—works as a corrective history, adjusting the Beats’ singular vision to include people from beyond the white literary and art worlds.

“I named this book The Brown Beatnik Tomes, because I was wondering what it would be like to be a Beatnik poet in 1950, 1960 in the middle of all that was going on and not being recognized,” Simmons said at the beginning of “Tender,” the album’s fourth track. “I couldn’t figure out where all the black Beatnik poets were at that time.”

Knowing laughter rose from the audience.

What Carter was doing in the late ’50s and early ’60s was perfecting his chops for unforgettable stints with such jazz icons as Miles Davis and Eric Dolphy, and later leading his own groups. His quartet at the July gig—with pianist Renee Rosnes, drummer Payton Crossley and tenor saxophonist Jimmy Greene—like all of his ensembles, had been carefully chosen. And the collective’s flawless precision that night was exuded during each tune they played, sounding particularly cohesive during a second set, closing with a feverish version of “You And The Night And The Music.” Carter and his ensemble held the audience in rapt attention that evening, some concertgoers swaying knowingly with each beat.

Given the swarm of devotees after the performance, anyone seeking more than a few minutes with the bassist required patience. But meeting and greeting his fans seemed like a priority.

Not long after the show, Carter set out for some gigs in Europe, but is set to return to the States for festival dates, including the Newport Jazz Festival on Aug. 3, and a stop in his hometown for the Detroit Jazz Festival over the Labor Day weekend, .

There’s a special quality to players from the Motor City, as detailed in Mark Stryker’s recent Jazz From Detroit, and Carter has a hunch about why that is.

“I think it had a lot to do with the music programs in the various schools,” Carter began. “Practically every high school had music courses where students could learn an instrument and perform in bands and orchestras. This was true at [Cass Technical High School], which I attended. But it was at many of the other schools—from elementary to intermediate to high schools. Nowadays, we’re fighting an uphill battle to keep the music and the arts in schools’ curriculums.”

Benefiting from that sort of education, Carter would go on to hone his craft on more than 2,220 recordings, a number that, according to Guinness World Records, makes him the most recorded bassist in history. He’d also make a 1991 appearance on “Verses From The Abstract,” a cut off A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory, introducing him to a new generation of listeners.

Although a historical line connects Carter to Doug Watkins (1934–’62) and Paul Chambers (1935–’69) and continues into the 21st century, the bassist is quick to assert a sense of individuality.

“I don’t look at it in those terms,” he said. “Yes, I succeeded [Chambers] at Cass Tech and in Miles’ band, but that’s about as far as I can go with any discussion about legacies. Paul was a fabulous musician and left us much too soon.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…