Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

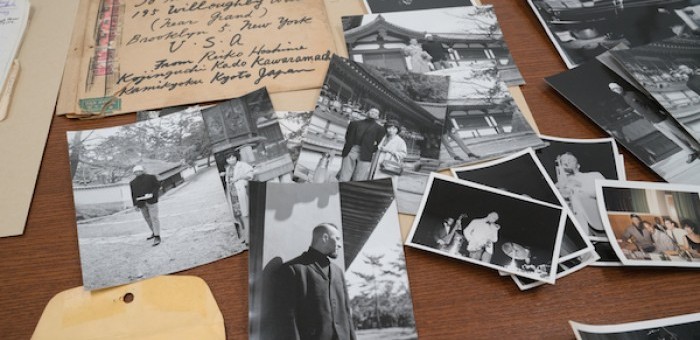

Photos from the Sonny Rollins Archive at the August Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.

(Photo: Jonathan Blanc/Schomburg Center, NYPL)Once or twice a week during his grade school years, Sonny Rollins, now 86, made the two-block walk to his local library from his Harlem flat on 137th Street between Lenox and 7th Avenues. Eight decades later, that same library, the August Schomburg Center for Research In Black Culture, has added Rollins’ remarkable personal archive to its enormous holdings of African-American materials, which includes the collections of Malcolm X, Melville Herskovits, John Henrik Clarke, Lorraine Hansberry, Maya Angelou, Nat King Cole, Mary Lou Williams, and, as of April, James Baldwin.

The Rollins collection spans approximately 1950 to 2014. Now in the beginning stages of being processed, catalogued and digitized, it’s a mother lode for the immortal tenor saxophonist’s worldwide legion of fans.

The materials include extensive personal and professional correspondence, including Rollins’ luminous love letters to his late wife, Lucille, in which he expresses his devotion in exquisitely tender prose, offers domestic instructions, gives reports on his sleeping habits and minor ailments, and muses on personnel difficulties. In an illustrated missive to saxophone guru Sigurd Raschèr, he requests an opinion on particular fingerings and the preferability of breathing through the mouth or the nose. The writing is exceptional and transparent. As Rollins does when playing at his best, he fully accesses his innermost feelings, triangulating all the implications of the motif or idea or emotion in question with virtuosity and elegance.

A short list of the original manuscripts of compositions and arrangements includes lead sheets for “Airegin,” “Sonnymoon For Two” and a never-performed piece circa 1950 titled “Night Blindness.” In original notebooks, sketchbooks and working materials, Rollins documents his studies in the art of music, the craft of the saxophone, and music theory, often complementing his praxis with eloquent personal meditations, aesthetic manifestos and intense self-criticism, punctuated by high-level, sometimes surrealistic imagery. Well-rendered, detailed pencil sketches on lined yellow paper of a lynx, a cheetah and an elephant bespeak Rollins’ early training as a draftsman. In addition to promotional shots, famous and obscure, there are revelatory personal photographs—in two, perhaps from 1963, a ‘frohawked Rollins meditates in lotus position amidst a group of Japanese fellow practitioners; in another, a suited Rollins stands in a club kitchen between sets, stretching an exercise band to its full extension.

Dozens of cassette and reel-to-reel tapes document practice sessions, rehearsals and performances. There are ample concert flyers and posters, copious business records (contracts, visa applications, tour plans), and abundant personal effects and memorabilia (a short list includes an oft-used Selmer saxophone, a traveling case, and reams of sheet music and songbooks, including Texas Jim Robertson’s Collection of Cowboy Songs and Songs of the Western Trail).

“I consider myself maybe a 75 percent self-taught musician,” said Rollins, who stopped performing in 2012. “On my steno pads, there’s a lot of my writing about scholarship and aspects of performing. Over the years, I saved posters from jobs, and things that happened every day in my career. Lucille kept all the books and contracts. All this stuff accumulated. I saw that Max Roach’s stuff went to the Library of Congress, and I thought: Why not place it in an archive? They’ve got a treasure trove of my personal life, a gang of stuff.”

For the initial processing, Rollins turned to James Goldwasser, a Los Angeles-based dealer in rare books, manuscripts and archives, and literary agent Chris Calhoun, with whom Goldwasser has partnered in inventorying and supervising the transfer of Roach’s archive to the Library of Congress and of Randy Weston’s archive to Harvard University. They are currently working on the archive of Yusef Lateef.

“When we were completing the appraisal and analysis of Randy’s papers in his lawyer’s office, Randy said he’d mentioned this project to an old friend who was thinking about doing something with his own papers, and that he’d told him to talk to us,” Goldwasser said. “Right there, Randy called Sonny and put me on the phone with him. Chris and I went to Sonny’s home in Woodstock and spent a few hours eyeballing what he had, and figuring out what we could do. Then I spent a week in Woodstock going through the archives. I’ve been a fan of Sonny most of my life, and almost every box I opened, I’d find something that got my blood racing. It was one thing after another where light was streaming in and illuminating this remarkable career.”

It would appear that Rollins and the Schomburg are a felicitous fit. “What I love about this particular collection is the texture,” said Shola Lynch, Curator of the Schomburg Moving Image and Recorded Sound Division, where the catalogued artifacts will reside. “You get to see his creative process over the years in bits and pieces. You see it through his doodles and his journaling; you’ll hopefully hear it through some of the audio recordings. We rarely get an opportunity to see the creative side of a black artist. Then, there’s the tenderness of the love letters. You look at Sonny Rollins, and you can’t imagine him whispering sweet nothings—and then you see him write ‘dearest beloved.’”

Schomburg Director Kevin Young focuses on Rollins’ “range and depth.” “Even in a writer, you rarely see such in-depth diary-keeping, such personal letters, such extensive notation and composition notes,” Young said. “You see not only the creative process, his song-making, but also his thinking about what it means to make songs. You see him searching throughout. Sonny Rollins is a very spiritual player and person, and you see up close the way he makes that happen on the page and in the recordings, which we look forward to hearing.”

Rollins looks forward to the end result as well. “I don’t know most of what’s in there,” he said. “People will tell me after they see it. I’ll go up there when it’s put together and I’ll be surprised.” DB

The text below replicates letters from Rollins that are included in the Schomburg archives:

“Wednesday Night, 10:10 p.m.”

Dearest one: I am writing to you from the club during intermissions as I failed to write to you last night. After work, I went to a studio out in the country and played for a while. It was good relief to do so, and when I came in this morning, I slept all day. I am in the middle of another personnel situation in that I hired Don Cherry, but released him tonight after he had worked only one night with us—last night. I would still like to use him sometime in the future, but once again, it is a matter of making a particular impression on this trip as an initial voyage west. It seems that it would require too much of a change to institute smoothly at this time, while creating this favorable impression. Actually, I have just begun to break in Ben, and achieve somewhat of a good rhythmic feeling. To add Don, as we tried, is analogous to starting this process all over again, or to starting a new group from scratch. So while I want to use him, for he has very good ideas, I can’t fit him into the scheme and still sound halfway presentable at this time. I’ll pay him for a week anyway…

I’ve just returned after finishing my second set, which went, I thought, rather well. We played “The Bridge” and also “Deep In A Dream Of You.” When I get off this morning, I must leave for San Jose at 6 a.m. to arrive at 7:30 for a breakfast meeting, which Mr. Piepenbrinck suggested I make if possible. This will in place of yesterday’s, Wednesday’s visit. I will still have the opportunity… [He must be writing this from San Francisco.] I will still have the opportunity of visiting the various labs and buildings as well as meeting with the Imperator, Ralph M . Lewis, for an interview. I just hope that I won’t be too tired while there or after I get back here. When I get home, I shall lay out my clothes and take a nap to 5:30, and then leave around 6. Maybe, since I slept all day, won’t be too tired. I think I hear the music from the record stopped, which means another set, so I’ll continue when this third set has ended.

Set #3 went all right, and now it’s after one, and time for the final performance at 1:20. I unfortunately could not allow Don to sit in and play before now, although he’s been here with his instrument all night. I gave him the bad news as we were getting set to come to work, and he came along anyway. Perhaps now that the bigger part of the crowd has gone, I’ll allow him to play with us for the last set. He’s a darned nice kid, and he understands completely. I’ll close for now with all my devotion to you intact.

Wednesday, February 28th, 5 a.m.

Dearly beloved: It’s extremely wonderful to have someone to love and do things for. Now that you are far away from me, it has brought a new dimension to my love for you, and I find myself overflowing with each thought of you, with all the things I want to do and buy for you and send you and surprise you with. I’ve already sent you one package, and you can expect some more surprises. I hope you are well and taking care of yourself and keeping Major in tow. Speaking of toe, how is your foot? Don’t hesitate to call Val if you find it bothersome, as they would all like to see you anyway, even under those circumstances.

I caught a cold yesterday while practicing at the club. I was in the basement while the others were rehearsing upstairs. It was the first good practice I’d had since New York, and I didn’t realize how cold it was until I felt my hands becoming numb!! The others had gone, and I was there alone. Later I learned that it was too cold for them upstairs in the club, so you can imagine how it was in the basement!! Anyway, I am now lying in bed with a sniffling nose and no Vicks. I did get some Vitamin C and an inhaler before going to work, and I should be over this shortly.

By the way, tomorrow we are supposed to do a TV show, Henry Morgan, who is now out here with a 90-minute night-time show. We had a nice crowd on Tuesday, and they were also rather appreciative. Well, baby, I must get under the covers of my king-sized bed and get some rest, so write soon.

Love Sonny.

The following are excerpts from Rollins’ philosophical and aesthetic observations on music:

1.

LOGICAL MUSIC: We have to release the music. We must be constantly alert for the sounds which will release the music.

Thursday, July __

On the initial set, we demonstrated the FACT of this logical music. We played “Dearly Beloved.” “Dearly Beloved” was played in an improvised manner. We utilized certain effects which had been rehearsed in sequence, in no particular sequence, but they were utilized, rather, where the movement dictated. Next we played “Oleo” and we thus concluded that set—short but sweet.

The lessons to be learned are that we as a group are able to function in a collective, intuitive effort, producing improvised music, or, rather, logical music.

Sunday evening: One complete composition was performed in the intuitive logical manner.

2.

The sameness which has been implied between love and hate also applies between success and failure. What then appears to be opposite sides of the pole may, in fact, be just that, but what must be stressed and what is usually overlooked is that both conditions are resident in the same pole. This, then, is to imply that the seemingly diverse conditions are in reality closely related. Now, let me begin by saying that many people who have succumbed to failure in one way or another have been just that close to success so as not to see it, and furthermore, just a small extra measure of endeavor would have resolved this unreal juxtaposition for them, and in their favor. The lesson to be drawn from this is, in a practical way, the lesson of perseverance, for we never realize how close we are to the positive expression of our endeavors or the far end of our pole.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…