Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

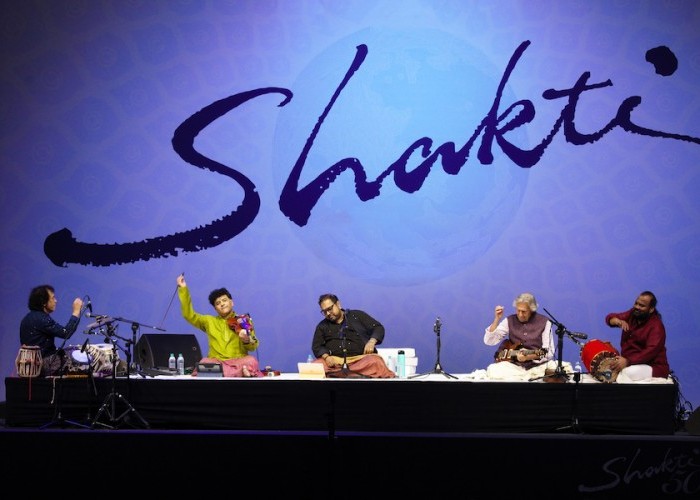

Shakti celebrates its 50th anniversary with a new album and tour.

(Photo: Pepe Gomes)There was a moment in 2017, following what was billed as his farewell tour in the States, that guitar avatar John McLaughlin was ready to pull the plug on touring altogether. An inherited progressive arthritic condition in his right hand was forcing him into semi-retirement. As he had explained to DownBeat at the time: “The American tour is it for me, because the situation with my hands is deteriorating. Short of a miracle, I think that’ll probably be it, at least in terms of touring.”

Enter American doctor Joe Dispenza, who helped heal McLaughlin’s arthritic hand through meditation and the power of a “mind-body connection” that has caused spontaneous remission in countless others. “He’s something else,” said the guitar great of Dr. Dispenza. “I had never met him, I just read about his technique. He had his back broken in three places and healed himself. And I said, ‘If he can fix his back in three places, I can fix my hand.’ And I did. I’m still working on it every day, but there’s no swelling, no pain. It’s far out, man!”

McLaughlin rebounded miraculously, recording two albums while sequestered at his home in Monaco during the pandemic — 2020’s Is That So? with Shakti mates Shankar Mahadevan on vocals and longtime partner Zakir Hussain on tablas, and 2021’s Liberation Time (both records on Abstract Logix). He followed that by celebrating his 80th year with a triumphant 4th Dimension Band tour of Europe in 2022. With the June 30 release of This Moment (Abstract Logix), McLaughlin is ready to hit the road once again, this time with Shakti, the pioneering Indo-jazz supergroup he formed with Hussain in 1973.

A new face joining McLaughlin, Hussain and Shakti percussionist V. Selvaganesh on the upcoming Shakti tour (which commences in late June with two nights at London’s Hammersmith Apollo before the American tour kicks off with an engagement in Boston on Aug. 17) is violinist Ganesh Rajagopalan, whose dazzling work throughout This Moment recalls the pyrotechnic, pulse-quickening playing of violin virtuoso L. Shankar from the original ’70s group. “We go back, actually, at least 20 years,” said McLaughlin of the one-time child prodigy Rajagopalan, who began performing in public at age 7. “Zakir and I had a gig with Gansesh and his brother Kumaresh just down the coast from me in Cannes, near Antibes. This was about 20 years ago and we’ve been friends ever since.”

“And bringing in Ganesh kind of harkened back to the original Shakti sound with L. Shankar’s violin,” Hussain added. “But with much more of an understanding of the harmonic elements and more like a concoction of our collective experiences over the last 50 years, all boiling down to this. The way we arranged the songs and the breaks and the way it all worked is very different from how we did it in the old Shakti way, where we would arrive in the studio and start playing live and it would be recorded. And then what was recorded was just there. And here we had the ability, the technology and the time to be able to fine-tune stuff that was put on the hard drive. And so it was a collective effort, but none of us were in the same room together. So in that sense, the product is much more carefully sculpted than in the ’70s.”

Violinist Rajagopalan has filled in nicely for the late Carnatic mandolin master U. Srinivas, a member of the late-’90s iteration of the band dubbed Remember Shakti. Srinivas died in September 2014, at age 45. “When we lost Srinivas, we were really just lost as a band,” said McLaughin. “And it took a long time for us to pull it together again.”

“It was a terrible shock to all of us,” added Hussain. “And suddenly Shakti just stopped in its tracks. It was impossible at that point for us to be able to even consider doing Shakti without Srinivas. I remember meeting John a little while after he had passed, and we just hugged and cried for such a long time. It was just one of those shocks that we thought that we would never recover from. And over the years some mending has happened, but the ache still exists.”

As a tribute to their late comrade, Shakti opens This Moment with a tune called “Shrini’s Dream.” (Shrini was a nickname for Srinivas). “It’s a kind of jazz-funk idea with an Indian motif that we were kind of fooling around with at a rehearsal on our last tour with Srinivas,” said Hussain. “Someone made an iPhone recording of it and then Shrini went home and, lo and behold, he decided to leave us and move on.”

Eight years after Srinivas passed, when McLaughlin, Hussain and Selvaganesh began working on This Moment, that original iPhone recording of their rehearsal jam with the mandolinist was found. “The plan then was, ‘OK, let’s do this,’” Hussain recalled. “So we all sat down and worked out our ideas and offered our collective tribute to the young maestro. It is a tribute about our humble reverence to his spirit. Shrini was not of this world. He was an angel, a spirit that just descended in our midst and showed us what being a good spirit is all about, and then decided to move on. We were all touched by his pristine purity, and so we just wanted to begin this album with an acknowledgment of how we felt about him.”

The traditional South Indian kriti “Giriraj Sudha” is also dedicated to the late mandolin master. “We decided we wanted to adapt this famous kriti, which is one that Srinivas like to play a lot,” said Hussain. [A version also appears on Remember Shakti’s 2001 live album Saturday Night In Bombay].

And while This Moment is being touted as Shakti’s first studio album in 45 years (since 1977’s Natural Elements), this was not your typical studio session where engineer and producer sit behind glass in the control room as the musicians play together in the live room. Listening to the remarkably intense, rapid-fire konnokol vocal exchanges between Hussain and Selvaganesh on “Mohaman,” for instance, it is difficult to imagine that they recorded this white-hot jam not sitting next to each other in the same studio but rather 3,000 miles apart. Or that McLaughlin added his signature fleet-fingered, cleanly articulated guitar solos to “Shrini’s Dream,” “Bending The Rules,”“Karuna” and “Sono Mama” from his home studio in Monaco.

“Working remotely on Is That So? spawned the idea that we must do a Shakti album,” said Hussain. “Because it seemed to work, that we could actually do it long distance, so to speak. At that point in our heads it wasn’t yet clear that we actually were approaching 50 years as a group. We just wanted to make a studio album, which Shakti had rarely done. The second and the third Shakti albums in the ’70s were studio products, but before that and after that, all the other Shakti albums were done live. So since we were confined to our respective spaces due to COVID, we thought it might be a good idea to initiate a studio album.”

The rhythm tandem of Shakti began laying down tracks that were simultaneously played from their respective home studios — Hussain in San Francisco, Selvagensh in Chennai, India. “We worked together on a click track and came up with all our parts and how we would interact under the song, with the breaks and all that stuff,” Hussain recalled. “So it was recorded together live but still long distance. And the rest of it was a process of sharing files and putting material on top of existing tracks. Then we as a group would get together on a Zoom or FaceTime call and review it, making suggestions for fixing or adding things or just leaving it as is.”

“Both Liberation Time and this album were mixed at a distance,” McLaughlin explained. “The guys didn’t want to mix it in India, they wanted a Western engineer because there’s more attention paid to the percussion in the West. In India, there’s less attention paid to percussion, it’s more about the voice and the other instruments. So I got my favorite engineer, George Murphy, who was in London (at Eastcote Studio). And using this app called Audiomovers attached to his computer, which was running the board in England, he sent me a signal that I was hearing in 24-bit/48kHz with a maximum delay of 90 milliseconds. Meanwhile, Selvaganesh was in Singapore with his headphones on, I’ve got my good studio speakers on in Monaco, Zakir is in San Francisco and George is engineering in London. So we’re mixing in four corners of the world but we’re hearing exactly what the engineer is hearing. So we can say, ‘Hey, George, stop here. There’s not enough of Zakir.’ Or, ‘There’s not enough of the voice.’ Or, ‘Bring this down, turn this up, space this a little bit.’ The technology now is phenomenal.”

Hussain added, “In a recording studio we’d have three days to come up with enough stuff to fill a 60-minute CD. So you rush through and put it all down in a hurry. But each of us being in our home studios because of the pandemic, we had a long time at our disposal to be able to try different things and take our time. So we were able to make this Shakti album be a better look-in as to where we all are as musicians at this point in our lives, with all the influences and inspirations and inputs that we have received as students of the art.”

This Moment, the group’s seventh outing together, captures Shakti once again stretching the boundaries of Hindustani and Carnatic music while injecting Western ideas of harmony into its successful world music formula. “That’s really what I’ve been trying to do since the ’70s,” said McLaughlin. “I studied North Indian flute and later studied South Indian veena with Dr. Ramanathan, who was a visiting scholar in the ethnomusicology department at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, because I wanted a solid foundation in this music. I didn’t want to become a classical Indian musician, actually. I just wanted to know the rules and regulations so I could play with these guys without them having to make a compromise for me. I mean, that’s the worst that can happen is when they have to lower the bar simply because the white boy’s in the band, you know? So I learned and now they can throw any raga, any time signature at me, and I’m a happy guy. And they’ve known this from the beginning.”

Added Hussain, “When John wants to interact with musicians which are somewhat other than the kind of music he grew up with, he takes the time to learn about that music and get comfortable in it. And in that way, he’s paying respect to the music. And that’s so special.”

At the same time, McLaughlin hasn’t let his reverence for North and South Indian musics inhibit his desire to occasionally bend the rules. “From the beginning of Shakti, I wanted to have that Western element of harmony in the music,” he said. “I’m a Western musician, and I want to stay a Western musician. All I wanted to do was have the pleasure to play with these guys but bring my side of things into it, which is harmony, which they don’t use in Indian classical music. And I want to bring in different harmonies, different scales — Hungarian minor, melodic minor, half-diminished — because they’re all related in some way. So I’m bending the rules, which is one of the titles on the album, Shankar’s tune. But I want to complement the guys, I want to push them. And you hear it, for example, in Shankar’s solo and also Ganesh’s solo on ‘Bending The Rules.’ The tune is in E major, but I’m moving up and changing the chord to A7#9 then bringing it into D♭ minor, and they’re reacting to what I’m doing. These guys in Shakti hear it now, because they know Western music. And so we’re able to converse in that way.”

McLaughlin’s sprightly fandango-flavored tune “Las Palmas,” for instance, goes well outside the strict boundaries of Hindustani or Carnatic music by incorporating flamenco styled palmas (rhythmic handicapping) into the fabric of the piece, which sit comfortably and organically right alongside konnakol (vocal syllables in South Indian Carnatic music) and the frantic tablas playing of Hussain. You can even hear a few spirited declarations of “olé” along the way on this tune that put McLaughlin in mind of his other late partner, flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia. Like other hybrid forms on This Moment, as well as other pieces in the Shakti canon, “Las Palmas” is the very definition of world music.

Elsewhere, McLaughlin further bends the rules through his judicious use of guitar synthesizer — triggering the sound of bamboo flute (bansuri) on “Shrini’s Dream” and “Bending The Rules,” then emulating a string section on the intros to his gentle “Karuna” and Hussain’s atmospheric, bluesy meditation “Changay Naino.” And his electronica-flavored synth bass groove on “Sono Mama” is something completely different from the original intent of the acoustic Shakti from the ’70s. This supergroup has clearly evolved over time and has embraced technology while incorporating other musical forms. And the legacy continues.

It was back in 1973 at Saint Thomas Church in midtown Manhattan that the original edition of Shakti made its first public concert appearance. But McLaughlin and Hussain had actually met three years earlier. “Zakir and I met in New York City during the summer of 1970 at a place in Greenwich Village called the House of Musical Traditions,” McLaughlin recalled. “I knew the people there, and I used to go there to check out the sitars and tambouras and other Indian instruments. And I told the proprietor, ‘If ever a great Indian musician comes into the store, ask him if he would give a friend of yours a lesson; doesn’t matter what instrument.” A few weeks later, I got a call about this great tabla player who was there and I said, ‘Ask him if he’ll give me a vocal lesson.’ So I went down to this store and Zakir, who was giving a rhythm workshop there, ended up giving me a vocal lesson. We just hit it off, and we really became pals.

“Then in ’72, we actually played together for the first time at Ali Akbar Khan’s house in the Bay Area. [Hussain was teaching at the Ali Akbar College of Music in Berkeley at the time.] And it was ridiculously pretentious, when you think about it. I mean, here’s the great sarod master Ali Akbar Khan sitting in his own chair at home, and I’m there with acoustic guitar and Zakir says, ‘Hey, man, want to jam?’ But when you’re young you don’t care. So we sat down and we played, and I had never felt so instantly free and comfortable and joyful. And Zakir felt it, too. We both felt it. And I think it was from that experience that Shakti was born.”

As Hussain recalled of that pivotal experience, “We jammed and it was like we had done this before. It never felt like we had to adjust or tell each other what to do. We just started playing, and it was just so right! And it took another year or two before John could put us all together to form Shakti, because he was still doing the Mahavishnu Orchestra at that time. Then, after we played a concert in New York in 1973, it was clear that there was something brewing here that was out of the ordinary. It was something special. So John arranged another concert in Southampton College on Long Island and people who attended just went nuts. And it was at that point that he floated the idea to us for us to play together as a band and travel.

“I guess he had been considering at that point moving on from Mahavishnu,” Hussain continued. “It was a very courageous decision that John took. He gave up a money-making machine like the Mahavishnu Orchestra and put himself in this situation with Shakti where there was no surety that this would survive, that this would even fly, that people would even accept it or understand what was happening. But he did it anyway. And while it did not fly as well as Mahavishnu, it did not lose money. It was doing enough. Still, the powers-that-be at CBS wanted to see platinum and gold albums, which Shakti was not doing. They wanted John to get back to playing electric music, and the contractual obligations finally forced him to move onwards from Shakti. I remember the day when he told us, ‘We have to stop this for now,’ and he was in tears at that time. And so we didn’t actually stop totally. We occasionally got together and played a few concerts here and there, but we did not tour as a band or make any more records until the late ’90s when we came back as Remember Shakti.”

Selvaganesh, son of the original Shakti ghatam (clay pot) player Vikku Vinayakram, was all of 8 years old when Shakti made its initial tour in 1975–’76. He ultimately became a member of Remember Shakti in the late ’90s and has developed into one of the leading kanjira (south Indian frame drum) players of his generation. He also has his own studio in Chennai, India, where he has done soundtracks for innumerable Bollywood films. “It’s been a moment of pride for both John and me to see Selva turn into this successful grown man,” said Hussain. “He’s a very prolific composer for the South Indian film industry. He even directed a movie [2008’s Vennila Kabadi Kuzhu]. So he has his fingers in many different pies. He’s a very creative young man and a very good sound engineer himself. And so he has brought himself into this modern world with the tools needed to be able to be valued not just for his playing, but for his overall understanding of the craft.”

“We’re all doing other things,” added McLaughlin. “Zakir’s got his classical things that he continues to do and he’s also doing gigs with his Masters of Percussion group and others [including recent collaborations with banjo legend Bela Fleck, bassist Edgar Meyer and Indian bansuri player Rakesh Chaurasia on As We Speak (see “Reviews,” page 40), jazz giant Charles Lloyd on 2022’s Sacred Thread with guitarist Julian Lage, Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart & Planet Drum on 2022’s In The Groove, and bassist Dave Holland and saxophonist Chris Potter, collectively known as the Crosscurrents Trio, on 2020’s Good Hope]. Selva does a lot of percussion concerts with his father, Vikku, and his son, Swaminathan. Ganesh has his own school happening now up in Seattle. And Shankar Mahadevan ... I mean, when you’ve sold over 200 million albums in India, you know you’ve got a career happening. So getting us all together was really an act of love on the part of everybody. Because every member in the band has a particularly strong love for Shakti.”

“I can’t yet digest that it’s been 50 years,” said Hussain. “We’ve obviously been in touch with each other and connected and done things over these years; different projects that we’ve been a part of. And so it’s not like we’ve been totally disconnected from each other. But it’s like coming back home after being away. Now I understand how the tribe felt when they finally reached the promised land.”

The pioneering world music band continues building bridges through music on its latest release, This Moment. “Shakti, obviously, was at the forefront of it way back when, 50 years ago,” added Hussain. “And now it is great that it is being welcomed back. And it’s just been amazing to be able to perform together, doing two-and-a-half-hour, non-stop concerts. I didn’t know that we had it in us to be able to do that, but here we are. And it felt like we just picked up where we left off.”

He added, “Shakti has arrived in terms of the awareness of each other’s ability to be able to live in each other’s house, so to say. With the old Shakti we were playing largely a South Indian-based material and John found his way in it, amazingly. And I have to say that he’s a one-of-a-kind musician. I mean, who else can be sitting with Paco de Lucia or Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, Carlos Santana, etc., and then also be sitting with Indian musicians and looking like he belongs? What an amazing life this man has had! The kind of inspiration he has spawned over the years in the world of music is equally influential in America, Europe, India, everywhere. This is something that is so unusual that you don’t see that happen with any one musician in that way. John is truly a world musician.”

“I’m so excited about this new album,” said McLaughlin. “You know, we’re not going to make $1 million off it, but if you can make back what you invest on a recording, we’re all happy. But every record is like a painting. And when I talk to my painter friends, they’ll do a new painting and they say, ‘Well, if it’s my last painting, it’s definitely the best thing I can do at this time.’ And I think that’s what it is with Shakti. It’s like a window into all of us and our collective lives and how we are at this time. Because by the time you get to hear us live, things will have changed.”

Until then, we have This Moment. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…