Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

John Dorhauer (center) leads the Heisenberg Uncertainty Players in a performance of “We Tear Down Our Coliseums” at Elmhurst College in Elmhurst, Illinois, on April 1.

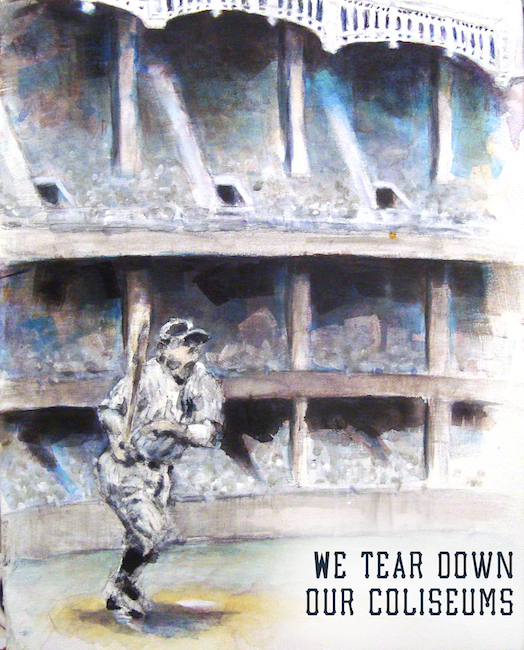

(Photo: Bill Parsons)On the eve of Major League Baseball’s 2017 opening day, composer John Dorhauer and his brother Adam Dorhauer, a painter, pitched jazz and images together in the premiere of “We Tear Down Our Coliseums,” evoking the legacy of the national pastime and its place in our imaginations.

A kaleidoscopic big band suite performed by the 17-piece Heisenberg Uncertainty Players, each of John’s nine music movements was accompanied by one of Adam’s original canvasses (most depicted architectural details), which he placed on an easel in front of the stage. “WTDOC” was nostalgic in theme but creatively complex and forward-looking, open-ended within a tight structure, just like a baseball game.

The performance took place in the small, black box Mill Theater at Elmhurst College in west suburban Chicago. On hand was an audience of about 70 students, friends and relatives who seemed unfazed by a section dedicated to atonalist Edgard Varése and quite willing to sing a chorus of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during a seventh inning stretch.

As a warmup, John Dorhauer conducted his band—five reeds, four trombones, four trumpets, electric guitar, bass and piano, and drums—through works from its standing repertoire, including his instrumental version of Lorde’s “Royals.”

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Players, apparently in their mid- to late 20s and including Dorhauer’s wife, Kelley, on alto saxophone, have been together more than five years; they hold down a twice-monthly gig at Phyllis’ Music Inn, in Chicago. They’ve developed a cohesive, warm ensemble sound, though each members’ reading and soloing skills seemed tested by the intricate section writing, dynamics, instructions and rhythmic changeups of Dorhauer’s charts.

Illustration by Adam Dorhauer

Conceptually, “WTDOC” was composed with the number nine as a key. Referring to the number of fielding positions, strikes in a perfect inning, innings in a game and feet between bases (90), the figure crops up specifically in the nine-pitch motif which opens a central section of the work, “Muehlebach Field,” from which massive blocks of ringing, orchestrated sound emerge.

According to Dorhauer’s notes, the blocks “represent the nine defensive positions, while the individual pitches, depicting batters and baserunners, utilize the only three pitches not included in those clusters.”

The whole of this movement is the composer’s attempt to “depict as literally as possible the action of a baseball game,” with direct reference to what the St. Louis Cardinals (Dorhauer’s home team) and the Milwaukee Brewers did, play by play, on August 31, 2016. But it wasn’t necessary to be steeped in the nuances of that contest to understand the music’s fearlessness, rigor and originality. Nor did the fact that the Dorhauer brothers dedicated this movement to the Negro League’s Kansas City Monarchs make much musical difference, though that shout-out added even more to the suite’s rich contextualization.

A six-page program with texts by both John and Adam provided a mass of information about the abandoned or decayed sites—including Elysian Fields (home of the first organized baseball game), the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium—they celebrated, inspired by a childhood baseball-intensive car trip they’d taken with their father and uncles. Jazz fans, however, could identify in Dorhauer’s pieces certain directions in big band music introduced by Stan Kenton, Gil Evans and Thad Jones, among others.

Illustration by Adam Dorhauer

Structurally, Dorhauer frequently developed sections like successive stages of fireworks. He employed syncopated bass lines over lightly-struck drums, ensemble backdrops rather than rhythm-section support for solos, episodes in odd meters and a waltz. At the start, he evoked the mists of history with airy effects from his saxophones, strange colors from the brass and melody tinged with melancholy. But the suite proceeded through a variety of moods, suggesting faceoffs between gladiatorial athletes, the see-sawing fortunes of opposing teams, measures of languor punctuated with sudden activity, moments of lyrical romance and reverie, blasts like line drives, waiting-for-the-ball-to-fall suspense, a drunken waltz out of Kurt Weill or Hanns Eisler, pneumatic ensemble inflations and deflations a la Roswell Rudd. There was some fleet, comparably straightahead writing, too, as if the composer had spent time studying Broadway musical comedy.

Whether John Dorhauer is conscious of much less steeped in all those precedents is perhaps less important than that such diverse elements seemed to sit comfortably and naturally on his present-day jazz composer’s palette. When the Heisenberg Uncertainty Players at the end of “We Tear Down Our Coliseums” launched into a reprise of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” over a New Orleans second-line beat, traditions of American sports and music were braided together inseparably.

We may tear down our coliseums or move on from big band foundations laid down by Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Count Basie. Yet in baseball and jazz the game remains the same: Swing for the fences, play with verve, take chances, be a team, exploit surprises. Using these strategies, the Dorhauers and Heisenberg Uncertainty Players are on track to scoring big, successful seasons, maybe eventual pennants. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…