Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

In Memoriam: Jack DeJohnette, 1942–2025

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

David Hazeltine (left), Todd Coolman, Eric Wyatt, Jimmy Heath, Joe Lovano, Ravi Coltrane, James Carter, James Brandon Lewis, (not seen, Victor Lewis on drums).

(Photo: John Abbott/www.johnabbottphoto.com)The cutting contest has a long and honorable tradition in jazz. So when six improbably gifted tenor saxophonists gathered on April 29 at Purchase College in Westchester County, New York—the occasion was a tribute to one of the music’s most expansive improvisers, Sonny Rollins—it was perhaps inevitable that the evening would slide into pyrotechnic display.

But for all the sparks that caught fire, the concert, part of a valuable new jazz series at Purchase, never raged out of control—thanks in no small measure to trumpeter Jon Faddis, a curator of the event, and NEA Jazz Master Jimmy Heath, its senior performer. Their humorous asides, musical and otherwise, helped keep egos at bay—assuring that Rollins’ generous spirit would be an unwavering presence in the college’s Pepsico Theater.

To the dismay of the packed crowd, Rollins, 86, had not made it down from his upstate home despite rumors that he might do so. But his contributions to the event were nonetheless concrete. He had chosen the saxophonists: Heath, Joe Lovano, Ravi Coltrane, James Carter, James Brandon Lewis and a late addition to the roster, Eric Wyatt, Rollins’ godson. And he had written or helped popularize most of the evening’s tunes.

Faddis, looming large physically and philosophically, set the tone early. Echoing Rollins’ ironic treatment of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” recorded with Don Cherry in 1962, he opened the show with an unaccompanied version of the national anthem laced with just enough bluesy ornamentation to suggest mild irreverence. Though Faddis would not return as a player until the finale, he remained on hand as emcee—a moderating influence throughout.

That influence was never more relevant than on the raucous ensemble number that followed the anthem: “Tenor Madness.” The tune, the title track from Rollins’ 1956 release on which John Coltrane appeared, provided an opportunity for the six saxophonists to blend as a section, and blend they did. But as they dug into their solos, their competitive instincts began to roil the proceedings. True to the tune’s title, a kind of madness—if a fine one—threatened to take hold.

Wielding the shiniest saxophone, Carter veered closest to the edge. As the choruses unfolded, he emerged as a monster of multiphonics—one with an apparently limitless capacity for slashing and burning his way through upper-register passages, even as he expended considerable energy sashaying to drummer Victor Lewis’ driving beat. If Carter bordered on a man possessed, the audience ate it up.

Saxophonist Lewis, the youngest of the performers, seemed headed in the same general direction—focused as he was on an anxious, staccato attack that alternately propelled the music and acted as a counterweight to it. Wyatt, for his part, added to the agitation. His lines, angular and marked by a predilection for disorienting intervallic leaps, amplified the fraught but pleasurable sense of destabilization.

Providing plenty of contrast was Heath, who took a more tempered tack. Melding with the urbane David Hazeltine on piano and Todd Coolman on bass—who, along with Lewis, had provided eminently adaptable backing for the front-line sound and fury—he eased into long legato passages separated by plenty of space and punctuated by flashes of virtuosity rendered all the more vivid by their sparseness.

Able-bodied and lucid at the age of 90, Heath’s perspective was evident on the ensemble pieces, to be sure, but more especially when he introduced his soprano saxophone on his big solo number, “On Green Dolphin Street.” Cap on, head bowed, horn pointed toward the floor, Heath, a diminutive figure, seemed nearly to disappear onstage—until he began playing. Suddenly he was transformed into the giant he is, by dint of his ability to mine the story-telling possibilities in a single note’s dynamics.

Ultimately, however, it fell to Lovano and Coltrane to capture the essence of Rollins’ free-associative, stream-of-consciousness approach. Individually, the saxophonists had each offered a master class in theme and variation. But, near the end of the show, they raised the stakes, joining forces to form the most fruitful pairing of the night, courtesy of Rollins’ “Airegin.”

Taken at breakneck speed, the tune, which Rollins first recorded with Miles Davis in 1954, provided a vehicle ripe for rewarding interplay, inviting to the Purchase stage the simpatico that the saxophonists had, along with Dave Liebman, nurtured in the collective Saxophone Summit.

In their colloquy, each artist drew liberally on the abundant raw material at hand—extending the tune’s central harmonic premise, picking up on one another’s ideas and extrapolating from them with the sort of immutable logic, impeccable taste and formidable energy for which Rollins is known. All of which built toward a raw but self-contained emotional peak achieved without the distracting bells and whistles less judicious players might employ.

The piece provided a natural lead-in for the night’s climactic number, “St. Thomas.” With the tune, Rollins’ jaunty hit from 1956’s Saxophone Colossus, the program came full circle, reintroducing the full ensemble for the first time since it massed for “Tenor Madness.” But this time, Faddis augmented the group. With a few short but searing bursts of his horn amid a tightly constructed solo, he signaled that the competitive fires would burn only briefly, and that the one-off assemblage of saxophonists would, after closing statements, go their separate ways. DB

Jack DeJohnette boasted a musical resume that was as long as it was fearsome.

Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

Goodwin was one of the most acclaimed, successful and influential jazz musicians of his generation.

Dec 9, 2025 12:28 PM

Gordon Goodwin, an award-winning saxophonist, pianist, bandleader, composer and arranger, died Dec. 8 in Los Angeles.…

Nov 13, 2025 10:00 AM

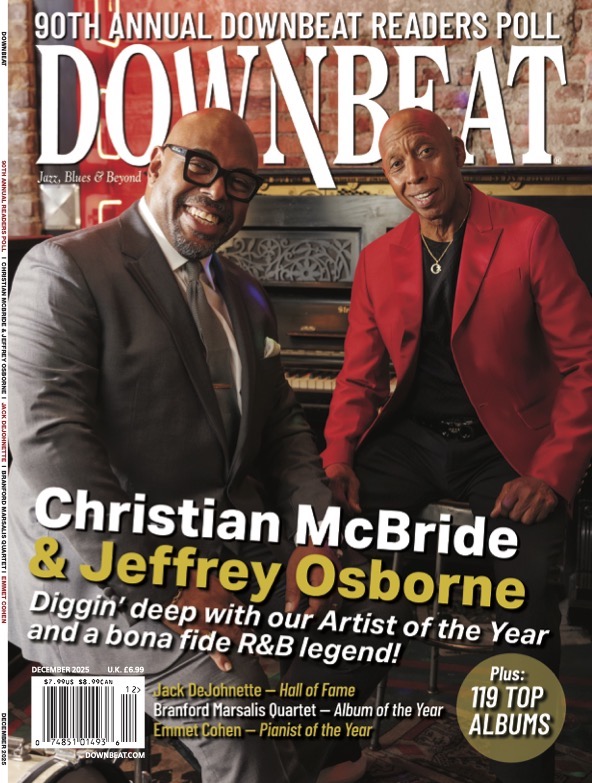

For results of DownBeat’s 90th Annual Readers Poll, complete with feature articles from our December 2025 issue,…

Flea has returned to his first instrument — the trumpet — and assembled a dream band of jazz musicians to record a new album.

Dec 2, 2025 2:01 AM

After a nearly five-decade career as one of his generation’s defining rock bassists, Flea has returned to his first…

To see the complete list of nominations for the 2026 Grammy Awards, go to grammy.com.

Nov 11, 2025 12:35 PM

The nominations for the 2026 Grammy Awards are in, with plenty to smile about for the worlds of jazz, blues and beyond.…