Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

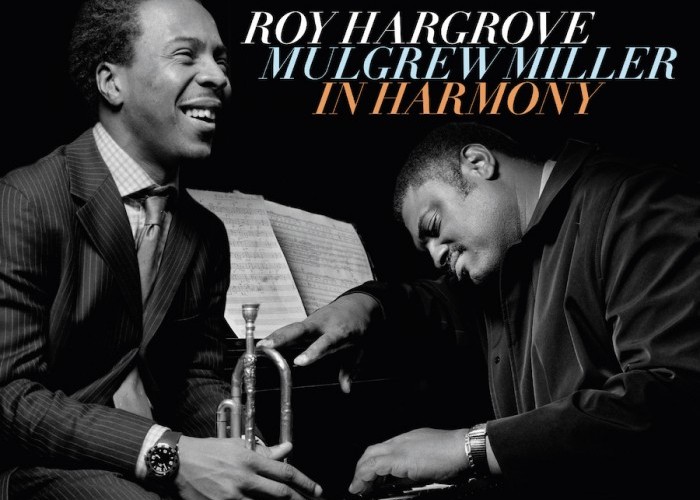

In Harmony is culled from live 2016 and 2017 duo performances by modern-day legends Roy Hargrove and Mulgrew Miller.

(Photo: Resonance)The history of jazz is fraught with artists who’ve died too young. But what lives on is their music — the legacy of distinctive recordings they leave behind, some of which are inevitably unveiled posthumously.

The latest such gift to jazz listeners is a previously unreleased recording of two concert dates with two modern-day legends: trumpeter Roy Hargrove (who died in 2018 at age 49) and pianist Mulgrew Miller (who died in 2013 at age 57). The appropriately titled In Harmony serves as a transportive masterpiece of improvised standards on Resonance Records. It is the culmination of a five-year project spearheaded by label co-president Zev Feldman, who serves as co-producer with Larry Clothier, Hargrove’s manager. Clothier recorded the shows in 2006 at New York’s Merkin Concert Hall and in 2007 at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, and the music was recently released as a two-album, full-packaged beauty for Record Store Day’s RSD Drop on July 17 with a limited run of 7,000 copies. (A two-CD version and digital edition will arrive on July 23.)

Feldman first heard the groove-, blues- and swing-steeped music at the home of jazz aficionado and producer Jacques Muyal in Geneva, Switzerland. It was 2016 and Feldman had just attended the jazzahead! conference in Bremen, Germany. He was immediately transfixed by the joyful interplay between the trumpeter and pianist. He heard Hargrove’s dynamic presence and piercing melodic phrasing through their take on Cole Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love,” his smoky tone on the ballad “This Is Always” and the emotive blues on his original “Blues For Mr. Hill.” He also fell in love with Miller’s sparkle on Jobim’s “Triste” and his dissonant edge on Dizzy Gillespie’s “Con Alma.” Together, the two were able to transform timeless music into a living transcendence. Not bad for shows that were performed without rehearsals or sound checks.

“This release had an interesting journey,” Feldman said in a phone conversation from his home base in Los Angeles. “Jacques has a lot of music in his house, and he asked me to listen to the Roy-Mulgrew recording. I was wowed. It was amazing. It was something different, and I started thinking about how to get this to be a part of the Resonance catalog. I wanted it badly. I was excited. Later that same year in Paris, Jean-Phillipe Allard played me the same music. But I knew that things were going to take time.”

Feldman contacted Clothier, who had been Hargrove’s manager for the breadth of the trumpeter’s career. “In general, I recorded a lot of Roy’s shows from the sound board,” Clothier said from his pandemic retreat in Arizona. “But there was nothing in my mind about releasing the duo shows. I’d always visit Jacques at his residence, and I’d bring all these tapes for him to listen to. He has a record and tape collection that you would not believe. This duo tape was one of many he had possession of from me.” Muyal was so impressed he passed it on to Allard, who had recently reactivated the Impulse! label. He expressed interest to Clothier with the proviso that he be the producer.

“Where did that come from?” Clothier said. “I told him that we didn’t have an interest in putting that out. I talked with Roy about it, but he wasn’t interested. He said he had other things going on at the moment.”

It wasn’t until after Hargrove died that the subject of releasing this duo project was revived.

Feldman reached out to Clothier and then contacted the family through the Roy Hargrove Legacy LLC, founded by Hargrove’s wife, Almut Brandes-Hargrove, and his daughter, Kamala Hargrove. He then contacted the Miller estate. After getting the green light from all parties, he began the project of documenting — with a thorough book of liner notes, interview testimonies from a variety of notables and prime photography.

At first glance, the Hargrove-Miller sessions come off as an unlikely pairing. The shy-but-brazen trumpeter and the mild-mannered pianist took different paths onto the jazz scene.

Hargrove got his break early, in 1988, as a junior at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts in Dallas. Clothier had been putting on shows at the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth. During a week-long stint at the venue, Wynton Marsalis gave a spur-of-the-moment workshop at the arts magnet school and was impressed by the young, promising trumpeter. He invited Hargrove to sit in with his band at the club. Hargrove finally showed up the final evening. “Roy was scared to death,” Clothier recalled. “Wynton asked him if he knew this song. Roy said no. He asked him about another. Roy said no. Then he asked him about a third standard, a bluesy song, and Roy said yes. They kicked off and everyone did their solos until Roy at the end. After a few notes, it was that clear that he could take someone’s breath away.”

From there, Hargrove was invited to sit in with Herbie Hancock and Bobby Hutcherson — who were reluctant, but later marveled. Dizzy Gillespie was convinced to have Hargrove play every night during the legend’s gig at the club.

Hargrove graduated high school and headed to Berklee College of Music on a scholarship. That lasted a year-and-a-half, and even then, he traveled to New York every weekend.

Contrast that with Miller, who experienced a less dramatic rise. He began his solo career with the 1985 album Keys To The City on Orrin Keepnews’ Landmark Records label. He also played as a formidable sideman with the likes of Woody Shaw, Art Blakey, Tony Williams, the Duke Ellington Orchestra, the Mercer Ellington Orchestra and, later, with Ron Carter in his Golden Striker Trio with guitarist Russell Malone.

Miller and Hargrove had shared a bandstand before — first at Bradley’s, the legendary Greenwich Village jazz hang, and later jamming on the same bill at the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival in Moscow, Idaho. Before he recorded his debut album in 2000, Hargrove met up with Miller as part of Superblue, an octet that recorded a self-titled album for Blue Note arranged by Don Sickler. In subsequent years, Miller subbed in Hargrove’s quintet, and both starred on the 2006 recording Dizzy’s Business (MCG Jazz) by the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band (Miller in the piano seat and Hargrove appearing as a guest).

So, playing together wasn’t new for either musician. On Jan. 15, 2006, came the first In Harmony show at the Kaufman Music Center’s Merkin Concert Hall.

“I got a request from them to have Roy perform,” Clothier said. “But the budget wasn’t very much to get excited about. We finally got around to doing an acoustic duo show, and it came down quickly to Mulgrew. It was as impromptu as you can get. In fact, because of a blizzard in New York, it was tentatively canceled.” The storm canceled Hargrove’s flight to New York. But Clothier lucked into a new one to Newark while Miller drove through the storm from Eastern Pennsylvania. They arrived in time for a quick set list discussion in the wings.

The show went so well that they decided to try it again a year later, this time on Miller’s home turf, the Williams Center for the Arts at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. Hence, the second disc that includes two inspired readings of “Monk’s Dream” and “Ruby, My Dear.” The show ended with a pop: an encore of Gillespie’s “Ow!”

Alto saxophonist Antonio Hart had history with both icons. He was a front-line player in Hargrove’s first band. “I was on Roy’s first three albums, and I toured with him for three years,” said Hart, a full-time professor of jazz studies at the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College City University in New York. “Roy was the kind of guy you only see a couple of times in your lifetime. He was gifted. He had a special genius light that he brought to the world where there’s a lot of darkness.”

As for Miller, “Mulgrew fits into that same category,” Hart said. “He had a different kind of energy in his music. I used to call him ‘Master Miller’ because he was more like a big brother, and even a father to me. He was very much a true original, a musical prophet.”

Hart said he looked forward to the album because it represents an opportunity to hear two of jazz’s lost heroes in one of their finest moments. Feldman is exuberant about the release of In Harmony, which puts on display the heartfelt interplay of two musicians, without other instruments, talking and listening and playing for each other. “Roy and Mulgrew are flying,” Feldman said. “This is a true example of the art of the duo, which is what Bradley’s offered so much in its history and what Spike Wilner is currently doing at Mezzrow.”

Feldman credited the project’s success to George Klabin, owner and founder of the Resonance label, who served as In Harmony’s executive producer. “George has been so supportive,” Feldman said. “He gave me the freedom to get the interviewers and the writers and photographs to make this into an investigative music package, especially with the vinyl edition. I love the vinyl. It’s in the girth of the project with the LPs. Even though the same liner note material will be on the CDs, the vinyl product gives more space to get people excited. We’re holding back the LP release date to the second Record Store Day to make this special.

“We’re confident this rare glimpse into two of jazz’s greatest artists will truly transport people in the same way.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…