Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

In Memoriam: Ken Peplowski, 1959–2026

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

“When I first emerged on the scene, I was dealing with working with a certain trumpet player who shall remain nameless,” Reed said. “It was very much an indoctrinating, dogmatic point of view, but it was all I knew.”

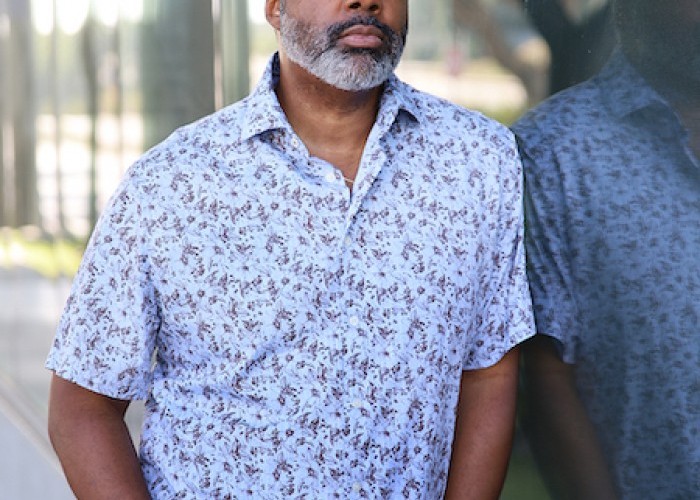

(Photo: Keith Wilson)As a piano-playing prodigy, Philadelphia native Eric Reed performed gospel music in his father’s church at age 5. By 7, he began formal study at Philadelphia’s Settlement Music School, and four years later, after his family moved to Los Angeles, he studied at the Richard D. Colburn School of Performing Arts, where he would eventually meet Wynton Marsalis during a workshop. By 18, Reed began subbing in Marsalis’ band, replacing Marcus Roberts in the trumpeter’s renowned septet the following year. Reed then worked briefly as a sideman with Freddie Hubbard and Joe Henderson before returning to Marsalis’ group, subsequently appearing on 1992’s Citi Movement, 1993’s In This House, On This Morning, 1996’s Jump Start And Jazz, 1997’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Blood On The Fields and 1998’s Standard Time, Vol. 5: The Midnight Blues. Reed also recorded first six albums as a leader during his tenure with Marsalis, including 1993’s It’s All Right To Swing and 1994’s The Swing And I, both titles reflecting the pianist’s urgent desire to fit in with the whole somewhat revisionist agenda of the Young Lions.

Through his formative years with Marsalis, his emergence as a leader on the New York jazz scene and the 30 albums that he made under his own name, Reed kept a secret that plagued him. Now, with the release of Black, Brown & Blue, his heartfelt tribute to jazz masters who came before him, the 52-year-old pianist has decided it was time to talk about it. Reed’s 31st as a leader and fourth for Smoke Sessions marks the first album that he has recorded while being completely open about his bisexuality, resulting in what he calls his most autobiographical release to date. As he stated in label’s press release: “It’s time for me to just go ahead and be completely authentic in every aspect of my life. That includes being more open about my sexuality and proactively moving into spaces connected with the LGBTQ+ community. Those aspects of my life were becoming more bold and more broad, and I could no longer keep them on the margins.”

In this phone interview, conducted in late February, Reed was calling from Knoxville, Tennessee, where he’s been teaching at the University of Tennessee since August 2020.

Bill Milkowski: How could an album of standards also be the most autobiographical record of your career to date?

Eric Reed: I knew that for this project I was doing for Smoke Sessions, I wanted to keep it simple. I pulled out songs that had been in my songbook for some time. And, again, I was trying to take these standards and make them more personal, but I also reached out to some other repertoire to sort of help me tell this story that I wanted to tell. Because so many things were happening all at once. Last June, when I made this recording, was also when I started talking about my sexuality to my family, starting with my mom.

That conversation was very revealing and it was also a little traumatic, which is to be expected. But it put me in a place of wanting to just face my fears and deal with all my insecurities. And so, having those first conversations with my mom about the entire spectrum of my sexuality was tough, but also something that I needed to do. Because I finally had to acknowledge that I could no longer hide my truth or protect people from my truth.

And around the same time, as I was planning the music for this recording, some of these songs started to come to me. Bill Withers’ “Lean On Me” is one of the first songs I learned how to play with two hands. And songs like Horace Silver’s “Peace” and McCoy Tyner’s “Search For Peace” seemed appropriate, considering the times that we’re living in now. I think we’re all searching for that and trying to find at least some modicum of peace, even if it’s just in our own little comforts.

Buster Williams’ composition “Christina” is part of my resume from working for some years in his band Something More. And Benny Golson’s tune “Along Came Betty” is something that I’ve always wanted to do with a kind of straight-eighth feel. These are songs that have stayed with me over time, so it’s autobiographical in a very direct sense but also in an abstract sense. Because I’m trying to galvanize and bring together all of the elements of my personal past and my musical past.

Milkowski: So that gospel element that seeps through on certain tunes, like on Wayne Shorter’s “Infant Eyes” and “Lean On Me,” is part of your own personal journey?

Reed: Absolutely. Always. Because it’s never left me. I’ve never made any conscious or explicit attempt to separate gospel from jazz and classical from R&B. For me, at this point in my growth, I just want to play music and not spend so much time codifying and labeling, if I can help it.

I wish that’s something that I could have thought about 20, 30 years ago, when I first got into this industry.

When I first emerged on the scene, I was dealing with working with a certain trumpet player who shall remain nameless. It was very much an indoctrinating, dogmatic point of view, but it was all I knew. I’m not making excuses, but I was a perfect candidate for that environment because I had grown up as an American under the cloud of religion and white patriarchy. So I was perfectly primed for just falling into another version of it, except run by a Black person.

Milkowski: At that point in your fledgling career, you were probably more concerned about swinging than any existential questions.

Reed: I was more concerned about swinging than anything else at all, period. Because I was told to believe that this was the way to go, that commercial music was trash. No fusion, no backbeat. And I’m 17, 18 thinking, “OK, this guy must know what he’s talking about. He’s made a lot of money. He’s paying me a lot of money. He’s on all these magazine covers. People are always asking him questions. The microphone is always in his face. He’s running this, he’s running that. He’s famous. So what the fuck do I know? I’m only 17. I’m going to push back against that?”

And it took me years and years and years to finally acknowledge that I was unhappy, that I was confused, and that I had felt betrayed by people close to me.

Milkowski: Given your very complicated relationship with the Black church, it’s interesting to see that some of that gospel element come out on your new record.

Reed: It’s such an intrinsic part of my musicality, so that’s never going to go anywhere. Regardless of the trauma that I experienced as a young queer Black kid growing up in the church and in the neighborhood — and let me tell you, the homophobia that runs rampant through the Black community is absolutely mind-boggling — the music itself was really where I felt most comfortable, even though many of the lyrics in these songs were quite traumatic. I mean, if you think about something like “Amazing Grace,” one of the most popular hymns ever written, it goes: “Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me.” So let’s just stop there. I mean, a wretch? Some of these lyrics are just so problematic. There’s another song called “We’re Blessed” by a woman named Dr. Margaret Douroux that goes: “We’re blessed. We’ve got shelter, clothing, food and strength. We don’t deserve it but yet we are blessed.” You’re trying to tell me that no person on Earth deserves to eat every single day? To be clothed, to be fed? I’ve got a problem with that.

Milkowski: There’s a gentle vibe that permeates Black, Brown & Blue. Both “Peace” and “Search For Peace” are extremely gentle pieces, as are Buster Williams’ “Christina” and Buddy Collette’s “Cheryl Ann.” And your interpretation of Duke Ellington’s “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good)” feels like you’re exploring the mystery and allure of that beautiful tune.

Reed: Yes, I’ve spent so much time just trying to uphold that philosophy of, “Swing, swing, swing, gotta swing hard!” that I really needed to explore other sides of myself.

Milkowski: Two of your albums from the early ’90s actually had that word “swing” in the title.

Reed: Exactly. The Swing And I and It’s Alright To Swing. Because at that time, I believe it was honest. It wasn’t just a matter of parroting somebody else’s vision, although at times it did feel that way, for sure. But to a certain degree, I did believe in it. Otherwise, it wouldn’t have come off very effectively. And while I did believe in it, I just didn’t allow myself to expand beyond it.

So this album, Black, Brown & Blue, is me at a very chill place. I don’t feel as though I have anything to prove anymore with regard to whether or not I can swing or whether or not I can play the piano. So I can explore the love that I’ve had for ’70s R&B, which is why I included Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise” and Bill Withers’ “Lean On Me,” and used two singers on those tunes who are not jazz singers at all [minister Calvin B. Rhone, a mentor to Reed, and David Daughtry, a gospel singer and Pentecostal worship leader of the West Angeles Church of God in Christ in Los Angeles].

We’ve always wanted to work together, and I found them very inspiring. So this album manifests the breadth of my musical acumen. But again, it aligns with where I am personally and spiritually and emotionally and psychologically … being in therapy and unpacking all that stuff, and being in a new relationship now. I can’t remember the last time I was in a relationship. It must have been 16, 17 years ago when I divorced my ex-wife. After that, I figured I was just done with relationships, that I’m not supposed to be in them, that I suck at them. And then, bam! Two months ago, I meet this guy who is nowhere near my age. So it’s presenting all kinds of challenges and questions and risks. And I’m here for all of it. Because this whole experience is definitely going to inform my next project, which is definitely going to be original music for sure. I got a lot of stories to tell.

Milkowski: Reggie Quinerly, who plays drums alongside bassist Luca Alemanno throughout this album, contributed the tune “Variation Twenty-Four,” which has a very zen-like calm about it. It’s got that dramatically unhurried quality, like a Betty Carter ballad tempo.

Reed: Yeah, that’s totally him. And that’s how he is as a person as well. He and Luka, who wrote that composition “One For E” for me, are both very important to me, particularly at that time we recorded this album. Because it was probably just a day or two before when I had that traumatic conversation with my mother, and then we went into the studio. So they were right there with me when I began to open up.

They’re both much younger than me, and that generation is more on the tolerant side, unlike my generation and older generations. These younger folks, the Millennials and Gen Z-ers, they’re like, “Yeah, whatever floats your boat. Do your thing.” They saw me as a person, not just as a musician. They’re much less judgmental than my generation was, and it’s beautiful to watch.

So now I feel as though I can just live, I can just exist, I can just be. And these younger musicians have allowed me this. Even some of the older musicians who are becoming more aware of my situation have been very affirming. They’re like, “Hey, Eric, we love you, do your thing, glad you’re happy.”

Oddly enough, I’ve not received any harsh looks or comments or pushback. I’m sure there’s comments behind my back; there always have been. But I can’t worry about that: I’m too busy being free.

Milkowski: You made a very thoughtful, very powerful statement in the liner notes to Black, Brown & Blue and included a kind of roll call of your elders and contemporaries who have helped you in your career. It seems that you have a nice support group out there.

Reed: Yeah, I really do. I’m in a very good place. And I found it in a rather unlikely way, because I thought that I would be forever connected to a previous employer.

You know, the idea of doing something else, I didn’t really think much about it. I didn’t think that it would ever manifest. And here I am some 30 years later on a completely different path, and still searching. I’m still looking for musical inspiration, and not just inside of jazz. I’m really allowing myself to explore what’s going on, and I spend a good deal of time with younger people and listen to their music — not that easy to do.

Just from a musical standpoint, these Gen Z-ers and younger Millennials are not so much into harmony. There’s a lot of three- and four-chord bands out there. Their lyrics, though, are incredible. They’re writing about some very powerful content and thoughts.

Milkowski: Another musical influence that’s been significant and ongoing for you in your career is Thelonious Monk. You did records dedicated to him — 2011’s Dancing Monk and 2012’s The Baddest Monk — as well as performing Monk tunes throughout your career. So it’s kind of appropriate that your new album ends with Monk’s “Ugly Beauty.”

Reed: Totally. “Ugly Beauty” is one of those haunting Thelonious Monk compositions that … it’s onomatopoeia. It sounds ugly in some spots and then there’s a great deal of beauty in other spots. But overall, everything Monk wrote has so much beauty in it, even inside of the dissonance. “Ugly Beauty,” for me, has represented sort of an ugly duckling [that transforms] into the graceful swan kind of thing, dealing with my own images and low self-esteem.

So “Ugly Beauty” is almost a theme song for me. Because there was so much ugliness in my life that I still have to unpack. And every time I unpack something, I find something beautiful in it. I’m like, “Wow, this happened to me, and this was really kind of fucked up.” But the other side of it is this beautiful side of what I learned from the experience ... what the pain taught me, what the trauma taught me, what the experience taught me. They always say, “If I knew then what I know now,” and it’s such a cliché. But I feel as though I’m in my second 20s now, and there’s so much that I did not know in my first 20s.

You don’t know what you don’t know. So here I am learning all these things about myself, learning these things about my personality, about my artistry, about my sexuality. And “Ugly Beauty” is sort of like the beginning of me saying, “I don’t have to hide anymore. I don’t have to hide who I am. I don’t have to hide how I feel. I don’t have to mask what I look like. This is it.” And you might think it’s ugly, but that’s on you. Because I think it’s beautiful, and I’m going to present it. DB

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…