Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

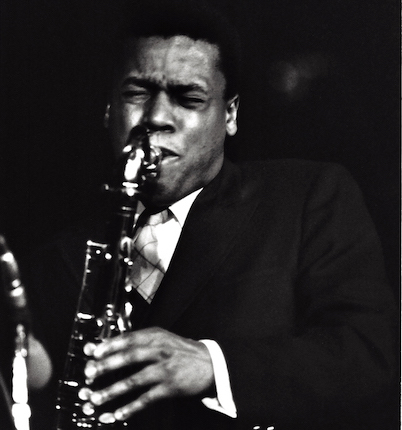

Wayne Shorter: 1933–2023

(Photo: Veryl Oakland)By the time the so-called riots of 1967 engulfed Wayne Shorter’s native Newark, New Jersey, the saxophonist had established a life well outside the war zone. A globetrotting 33-year-old, he was working at the pinnacle of the jazz world in Miles Davis’ groups and as a leader with a recording contract on Blue Note.

But even as his reputation grew, Shorter never strayed too far from his spiritual roots. For all the serenity of his demeanor and the discipline of his art, his output was imbued with the radical instincts reflected in the events of ’67. And while those instincts were sometimes expressed in oblique and epigrammatic terms, their origins were not abstract.

As an African American born in 1933 and growing up in the hardscrabble Ironbound District, he would have seen firsthand the inequities of life beyond the general privations of the Depression. Even as both his parents toiled at blue-collar jobs — his father welding at a factory, his mother sewing for a furrier — both would have been largely shut out from city largesse because of their skin color. The city power structure would not undergo meaningful change until the post-’67 period.

Shorter found refuge — and, perhaps, a kind of rebellion — in the satisfaction that expression through the visual arts could provide. He made no secret of his fondness for fantasy, especially superheroes, and he drew them incessantly. He would become a superhero of sorts to legions of fans by painting on an aural canvas, though his drawings were good enough to win a citywide contest that gained him admission to Arts High, a locus of educational innovation.

At Arts High, where he is said to have begun as a somewhat indifferent student, one teacher, Achilles D’Amico, helped change his life. A local legend, D’Amico had an expansive approach to teaching music that was instrumental in Shorter’s decision to become involved in the school’s rich music program. In it, he could compare notes with like-minded students who went on to fruitful, if lesser-known careers — musicians like saxophonist Harold Van Pelt, who became a stalwart on the R&B scene, and pianist Richie McCrae, who distinguished himself as an exponent of soul-jazz.

Meanwhile, Shorter would be heir to the outsize legacy of another student whose stature would rival his own: Sarah Vaughan. Though she was nearly a decade older than Shorter, he surely would have heard of her exploits at the school, where she was enrolled until her closely watched career began its rapid upward trajectory.

That success could have served as a model. As Shorter entered his teens, Vaughan had already made her mark as a member of Billy Eckstine’s vaunted big band. Formed in bebop’s early years, the band featured a constellation of the music’s most celebrated players, among them Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, whose revolutionary style, musical and otherwise, became a lodestar for the young Shorter. Reshaping his look and sound, he became known for sporting high-bebop fashion with a musical flare to match. At some point, Shorter acquired the moniker The Newark Flash.

Beboppers could be heard around Newark in venues big and small. Most of the marquee names played the 2,000-seat Adams Theatre. Practitioners of this new music also played smaller spots, where they might be freer to indulge their artistic and other appetites than in some of the higher-profile clubs across the river in New York. If the youthful Shorter had the wherewithal, this hipper scene would have been available to him at celebrated spots like Lloyd’s Manor, on Beacon Street, where Gillespie, Davis and other jazz luminaries sometimes hung their horns.

As a practical matter, Shorter’s instincts were most productively nurtured on the bandstand with freethinking local bandleaders who booked dates in New York but leaned heavily on the circuit of spots in secondary cities with bustling scenes, like Newark. Notable among those leaders were the twin Phipps brothers, saxophonist Bill and pianist Nat, who formed the Nat Phipps Big Band, a way station for some of the era’s most adventurous musicians. One, trombonist Grachan Moncur III, would later hire Shorter — along with Herbie Hancock, Cecil McBee and Tony Williams — for his own Blue Note album.

Influences beyond the strictly musical were also part of Newark’s cultural milieu. Most famously, Amiri Baraka, a direct contemporary of Shorter’s, was becoming known around town as a young poet with revolutionary aspirations and a taste for jazz.

Alternately known as Leroy Jones or Leroi Jones, Baraka, who would later contribute to DownBeat, had an interest in cultivating associations with musicians and, well into his later years, could be heard swapping stories with top players between sets in stately venues like the Newark Museum, a world apart from the one in which he and Shorter operated as young men.

Mainstays of that world are long gone, and parts of Newark have never recovered from the events of ’67. At the same time, the city has regained some of its jazz luster with the founding of radio station WBGO, new presenting clubs and the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, where Shorter appeared in 2017 to receive the key to the city from a representative of Mayor Ras Baraka, Amiri’s son.

That a Baraka was mayor was indisputably a sign of progress, and the gesture was a welcome one. But it merely confirmed that if, as Amiri once wrote, “the music reflects the people,” then a native son named Shorter did very well by his hometown friends, fans and family. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…