Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“The more sophisticated the lyric, the easier the melody should be,” Lins offered as a songwriting guideline.

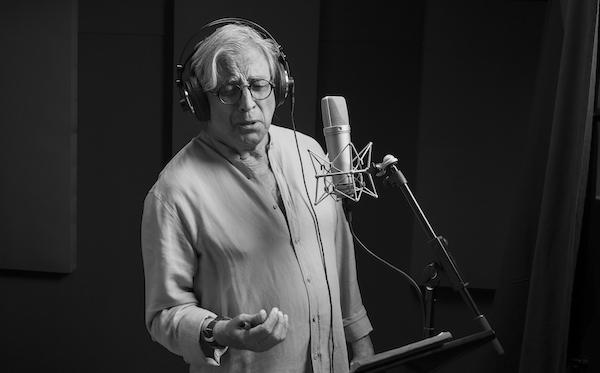

(Photo: Bruno Barata)Five years ago, the mighty Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy, paid lavish tribute to Quincy Jones on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

On the festival’s opening night, the large arena stage kept sonically active for a few hours, replete with rhythm section, big band and orchestral canvases, on-stage interview segments with Jones and, from the Brazilian contingent of Jones’ broad musical life, singer-songwriter Ivan Lins.

In terms of important Brazilian musicians with links to American music, Lins’ appearance at Jones’ grand party made perfect sense. His signature and oft-covered song “Love Dance” was sent into popular orbit by George Benson on the guitarist’s Jones-produced 1980 album Give Me The Night. Jones became an instant Lins fan after being introduced to the Brazilian’s discography by Los Angeles-based percussionist and first-call studio player Paulinho da Costa.

Soon after, Lins found himself and his career in friendly embrace of Jones. “He’s my godfather, musically,” Lins says. “He put my music around the world.” Reflecting on that evening in Umbria, he comments, “It was amazing that night — orchestra and all.”

Despite his legendary status both in Brazilian and American music circles — with a catalog of recorded original songs numbering more than 700 and counting — Lins remains, in some ways, an undersung hero of musical Braziliana of the past half century. Although he possesses a humble and distinctive strength as a singer in his own right, his deepest impact has been in the wings of music, where songwriters dwell.

For a substantial primer in Lins’ musical world, proceed to the new album My Heart Speaks (Resonance Records), a lush and orchestral treatment of 11 Lins songs spanning a few decades. The musical forces involved include the Tbilisi Symphony Orchestra (from the Republic of Georgia) and cameos by vocalists Diane Reeves, Jane Monheit and newcomer Tawanda, along with trumpeter Randy Brecker — all under the conceptual/producer aegis of Resonance founder George Klabin and arranger Kuno Schmid.

When it comes to preferred settings for his songs, Lins confesses to favoring a bigger-is-better aesthetic. He counts his work with orchestras over the years as his favorite projects. “If I was a rich guy, all my albums would have orchestra or a big band,” he laughs. In Tblisi, he says, “The orchestra sounded beautiful, and it was a beautiful theater.”

Lins, 78, was at home in Rio de Janerio when DownBeat connected for a phone interview, as he was easing out of a relaxed summer into an upcoming appearance at Sao Paulo’s eclectic “The Town” festival.

Seeds of My Heart Speaks were inadvertently sown by an earlier Resonance release, the Lins tribute album Night Kisses: A Tribute To Ivan Lins. Klaban invited Lins to write notes for the album, in which he praised “the great arrangers — Dave Grusin, Bob James, Josh Nelson and especially Kuno.” In turn, Schmid and Klabin proposed a new, ambitious Lins project, with orchestra in tow. Lins’ European agent, Catherine Mayer, recommended the Tblisi orchestra, under the baton of maestro Vakhtang Kakhidze.

When it came to repertoire, Lins intentionally left the curatorial duties to Klabin and Schmid. “I didn’t want to suggest songs because I really love my music. Any song they suggested is gonna be great. It was amazing, you know, because I got surprised with some songs like ‘Não há Porque,’” a decidedly non-commercial mid-’70s song among many protest songs Lins penned during periods of unrest and dictatorship in Brazil. “I never could even imagine that they were going to choose this song. I was really happy with the songs they chose. That showed me that they have very good taste,” he laughs.

Lins’ unique, understated vocal style graces several of the songs on My Heart Speaks, but the songs take on a different musical character in the vocal embrace of accomplished singers Reeves, Monheit and Tawanda. He is very accustomed to hearing his songs spring to new life via the famous voices of others.

“Everybody thinks that I’m a performer or a pianist,” he asserts, “but what I like the most is to write songs. And when I started to write songs, you know, I wasn’t a singer. I used to write songs for different people, singers that I was dreaming of. Who knows, maybe Frank Sinatra can record this, or Stevie Wonder, or the great Brazilian singers like Elis Regina,” who cut Lins’ first hit, “Madalena,” later recorded by Ella Fitzgerald.

“Suddenly, they discovered me and started to record me,” he says. “I used to have trios or quartets, playing instrumental. And then the songwriter started to take control over me.”

His own strange tale of reluctant acceptance of his vocal spotlight comes with coercive libations attached. “Somebody in the record company started saying, ‘Why not sing your songs, man?’ One day, I remember they knew that I loved caipirinha (a popular Brazilian cocktail, made from cachaça). I start to drink caipirinhas. I was almost drunk when I said yes,” he remembers with a laugh. “And the first time I went in the studio to sing, they did the same, and I did the same. I was so scared. I drank too much caipirinha before, and I couldn’t sing. We had to postpone the session. On the second, they prohibited me from drinking.

“Then, I started my career as a singer.”

One song that leaps out of his catalogue is the wildly popular and frequently covered “Love Dance.” Asked about his favorite versions of the song, Lins immediately answers, “One that I like the most is the first one, by George Benson. There’s one that I really love, too, by Diana Krall. Nancy Wilson did a great one, too, as did Barbra Streisand, and Shirley Horn did a great version, too.

“I usually do songs for the Brazilian market and the song is almost unknown here. Sometimes, I sing it here and people come and say, ‘Oh, it’s a new song?’ [laughs] No, it’s from 1979. I never thought that was going to go into the international market. Quincy, with his sensibility, picked up the song and put it with George Benson. It is still one of my favorite songs. I was very inspired doing that song.”

Generally, Lins’ song catalogue exemplifies the delicate balance of melodic, infectious and often romantic expression with subtle harmonic shifts or other signs of exploration. The accessible-adventurous impulse can be linked to such other Brazilian songwriters as Antonio Carlos Jobim and Caetano Veloso, going back to the 1960s. “Well, with that generation, at that time, we had a dictatorship,” Lins says. “We had to fight against the censorship and to go around the bush, with the censorship. We had to be very creative.

“With the bossa nova, people started to reach the international market. The important and best-known Brazilian musicians were those like Jobim and Milton Nascimento.”

Also on his list of Brazilian greats, Lins adds that “Sergio Mendes was very important. I know a lot of people used to complain about him, but he was extremely important for the Brazilian music, internationally. He made great albums, and he exposed a lot of different composers from Brazil. And he was always looking for the future, [looking to] technology and trying to explore with different sounds. We always had a great relationship. He was really always nice to me.”

Lins explains that his extant songbook involves 700-plus titles, which doesn’t account for an untold number of unfinished songs and fragments, contained on hard drives and, from earlier times, about 200 cassette tapes in a box “with a lot of ideas.” But he says he’s been lazy about listening to them.

“I’m a little bit of a compulsive songwriter,” he admits. “I love to write songs. I will put ideas in my digital recorder. I don’t want to be listening all the time, so I wait one week to sometimes two months, and come back to listen that idea. Then the idea sounds fresh for me. ‘Aha. I did that?’ Sometimes I get surprised, and then I start to work over the idea and write a song. Sometimes I’ll write two or three songs a day.

“The inspiration comes when I’m playing. I used to play almost every day, to prepare for the next show or set list and play the songs. Sometimes, some ideas would come to me. I have a digital recorder, and I push the record button. It’s faster than to write it on paper. When inspiration comes, you have to be ready.”

Although Lins has written lyrics to his tunes, often the words come from other poetic sources, including a long association with Vitor Martins. In the case of one of his more popular tunes, “Começar de Novo,” lyrics include both Martins’ and an English lyric by American songwriting legends Alan and Marilyn Bergman, under the English title “The Island.”

The songwriter is well aware of the delicate dance of melody and lyric in his work. “I love my melodies,” Lins explains, “and the melody works for the words. Sometimes the poetry is sophisticated. The more sophisticated the lyric, the easier the melody should be. That’s a concept. I used to do music for theater in the ’70s. There, the words are really more important than the melody. The melody has to just work for the lyrics and the message.”

Lins’ songs can take on a life of their own and show up in auspicious times and places. This year, for instance, his 1980 song “Um Novo Tempo,” addressing a U.S.-backed regime in Brazil, was played in Beijing’s Tianenman Square, timed with the arrival of current Brazilian president Lula da Silva. The songwriter was moved by the song’s Beijing moment.

“The lyrics are really a very hopeful message. People love to sing that song here because the last four years were really bad for us (under the right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro). But we never lose the hope. Hopeful songs started to be played here, not only ‘Um Novo Tempo,’ and other songwriters started to write hopeful songs, you know, dreaming with a ‘new time.’ It’s a sort of a hopeful anthem, in a way.”

Looking back over his 50-plus years in music, and specifically the songwriting art, Lins recognizes certain traits and objectives driving his artistic evolution. “I always pursued beauty and spiritual feelings, the good feelings. If you read the lyrics of my whole work, it’s rare that you’re gonna see something rude or negative or bad.

“I have no problem with calling out problems. But you have to say that this is gonna change. We can fight. We can sing. We can dance. And we can look toward the future and try to do something to get better. And that’s the target of my music.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…