Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

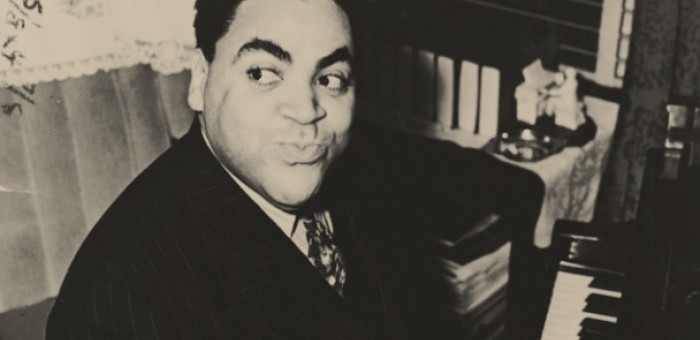

Music by Fats Waller appears on The Savory Collection, Vol. 3.

(Photo: Courtesy National Jazz Museum in Harlem)Jazz has always felt an acute discomfort in the close company of acceptance. For a music that takes pride in its cultural autonomy, great acclaim seems frightening, as if it might rob jazz of its rightful place at the margins of American culture and its self-ennobling outsider status.

So how do we explain the phenomenon of swing, which in the late ’30s made jazz the most popular music in the country? Maybe by noting that as the first generation of jazz critics was celebrating it as an “art,” a few fans were suspicious of its popularity. What was “real” jazz and what was just “commercial”? It was the first important debate over identity in jazz history.

There was irony here. Basie, Goodman, Ellington, Lester Young and Charlie Christian were in the creative primes of their careers. Yet, the hippest of the hip found the “commercial” motives of bands corrupting. So they rebelled against swing and embraced, of all things, Dixieland as the purest expression of real jazz. This may seem strange today, but keep two things in mind: Jazz was still young in 1938 and didn’t yet offer a lot of choices. Second, the first jazz histories and record reissues were just coming out. A foundation mythology was under construction.

People were discovering things they’d missed. Dixieland had adapted swing’s 4/4 rhythms and was still attracting top musicians. Much of it was astonishingly good. Eddie Condon became its chief advocate and publicist. When Commodore Records became the first American jazz label in 1938 and Condon its principal brain trust, Dixie was further sanctified and became a kind of retro/avant-garde credential for the rebels who saw themselves apart from the jazz-pop mainstream. To them, its backroom, jam-session quality felt more impulsive and spontaneous than the slick acrobatics of the bands.

This bit of context may help explain why the imprint of Fats Waller, Eddie Condon, Albert Ammons and others is so prominent in The Savory Collection, Vol. 3: Honeysuckle Rose—Fats Waller &Friends (National Jazz Museum in Harlem/Apple Music), a collection of radio air-checks recorded privately by Bill Savory between 1938—’40. Savory was a man whose tastes were well aligned with his time, as is this scrapbook of broadcast mementos, which nicely reflects some of the polarities of jazz at that moment.

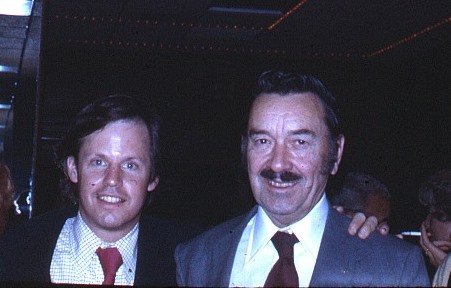

A photo of the author (left) with Bill Savory in 1979. (Photo: Courtesy of the author)

Boogie woogie, for instance, with its shuffling bass and simple riffs, was as retro as ragtime in 1939, an archaic contrast to the nuanced modernity of Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum. But few whites had ever heard its rolling thunder. So that made it new. Ammons, one of its pioneers, is heard on “Boogie Woogie Stomp.” It is essentially a piano set-piece that had already become the basis of Tommy Dorsey’s 1937 “Boogie Woogie” and would achieve a supreme immortality in wartime as “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” by the Andrews Sisters. Here it is, rediscovered but still in its native saloon attire.

More than a third of this collection includes a previously unknown WNEW program built around Jack and Charlie Teagarden, Pee Wee Russell, Bud Freeman and guest star Fats Waller. Organized by Condon, it captures the loose, go-to-town, ensembles and unencumbered solos that the purists of the swing era felt the big bands weren’t delivering. With Waller, Russell and the slippery grace of Teagarden all in fighting form, it burns with an energy and substance that belies the formulaic stereotypes of Dixieland. You won’t have to hide this as a guilty pleasure, nor the too brief “China Boy” with clarinetist Edmond Hall in the same hot-music genre.

Reflecting more contemporary standards are a pair of Benny Carter performances from the Savoy Ballroom, and two sizzling Roy Eldridge solos with CBS house band from a Saturday Night Swing Club show. The second, “Liza,” features rare extended drum work by Chick Webb. It’s the only title that has been previously issued.

Sitting on the threshold of the future, however, are the ten crackling John Kirby Sextet pieces taken mostly from his CBS radio show, Flow Gently Sweet Rhythm, the summer of 1940. If the Condon branch of the jazz world favored the freedom of small group abandon, this small group preferred the tightly knitted miniatures of big band discipline.

The soul of the Kirby sound centered around Charlie Shavers, whose muted trumpet imposed a surgical, almost dainty precision on the music’s intricate mechanisms. He also composed much of the repertoire, which included such all-time standards as “Undecided” and “Pastel Blue” (which Thelonious Monk borrowed from in composing “Blue Monk”). Shavers and pianist Billy Kyle have a bracing freshness that holds its snap well and swings hard on “Rehearsin’ For A Nervous Breakdown” and “Front And Center.” Its passion, like its heat, is implied. The resourceful arrangements should be a part of any jazz studies program.

One production reservation. This is unique historic material from an increasingly distant point in jazz history and warrants appropriate packaging. The discography provides only recording dates, nothing on source programming. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…