Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

In Memoriam: Jack DeJohnette, 1942–2025

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

Charlie Parker (1920–1955)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress )To say that Charlie “Yardbird” Parker was one of the greatest jazz musicians who ever lived is a bit like saying the Mona Lisa is a well-known painting.

In the jazz world, Parker is a towering figure, a founding father whose only other peer would be Louis Armstrong. It isn’t just that bebop, which remains the basis for modern mainstream jazz and a substantial amount of its avant-garde, is essentially his invention; for jazz educators, Parker’s music is what Shakespeare is to English teachers, not just a curricular keystone, but a central component in understanding how the language works. It would be hard to imagine what the music would sound like had Bird’s compositions and recordings never existed.

Yet when Parker died, on March 12, 1955, The New York Times responded with a death notice that read more like a police report than a tribute to a musical great. Although the story acknowledged that Bird was “one of the founders of progressive jazz, or be-bop” and was a “virtuoso of the alto saxophone,” most of the Times’ item was devoted to the circumstances of his death, due to lobar pneumonia, in the apartment of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter (aka Kathleen Annie Pannonica Rothschild). “The police said Mr. Parker was about 53 years old,” the paper reported.

He was actually just 34.

While the establishment took little note of Parker’s passing, the jazz world was in a frenzy of mourning and remembrance. The poet Ted Joans, who once roomed with Parker, organized a graffiti campaign with some friends, plastering alleyways, jazz club washrooms and other hipster haunts with a heartfelt message: “Bird Lives!” Although in some sense an act of rebellion, insisting that genius like his could never be extinguished, the phrase gradually became a jazz credo, a testament to the enduring power of the bop aesthetic.

Well, for a few decades, anyway. “Unfortunately, I do not have the sense that young players in college learn his music the same way we did when learning how to play,” said drummer Terri Lyne Carrington, who with alto saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa will be co-headlining a Charlie Parker-based tour, Fly Higher, through the coming year.

“When I was in school at Berklee College of Music in the ’80s, people were walking around with ‘Bird Lives’ T-shirts on. I don’t see that anymore. Then, people really understood the importance of learning as much history as possible before finding their own sound, or at least doing it simultaneously. All the modern players that I knew had a deep understanding of Charlie Parker and the repertoire—people like Greg Osby and Steve Coleman, though they did not necessarily play that repertoire or Bird licks.”

In fairness, it’s worth asking whether Parker himself, had he lived to some ripe old age, wouldn’t also have moved on from the sounds of his youth. Still, Carrington’s observation raises a crucial conundrum: How can Charlie Parker be both historically significant and currently topical? Which parts of his sound and myth have held on, and which have faded away? How exactly does Bird live in 2020?

Charles Parker Jr. was born on Aug. 29, 1920, in Kansas City, Kansas. His father, Charles Sr., a Pullman cook, was originally from Mississippi; his mother, Addie, Charles’ second wife, hailed from Oklahoma. Addie, by all accounts, was a doting and protective mother, while Charles Sr. was a heavy drinker, and frequently absent. By the time the boy was 10, his parents had split up, with Addie and young Charlie moving across the river to Kansas City, Missouri.

How Charlie grew up is a story that, often as not, relies mostly on mythology. We can blame him for much of that, as Bird seemed to delight in preying on the credulity of those willing to interview him. For instance, in an interview published in the Sept. 9, 1949, issue of DownBeat, Parker told Michael Levin and John S. Wilson that he bought his first saxophone at age 11, and that he did so after being inspired by the sound of Rudy Vallée. Other stories have him turning pro at the prodigious age of 13.

Perhaps the most accurate account of Parker’s youth can be found in Stanley Crouch’s assiduously researched Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker. Based on decades of research, including extensive interviews with people Parker grew up with, Crouch’s version doesn’t mention Vallée. Instead, his reporting suggests that Bird didn’t really take to the alto until he was at Lincoln High School, where he quickly rose to first chair in the school band.

Cocky and audacious, he was eager to move beyond his school music experience, and when he was laughed off the bandstand after his first attempt to play with the pros at the High Hat Club, his response wasn’t to give up but to practice obsessively, showing a determination that did not crop up elsewhere in his schoolwork. “I used to put in at least from 11 to 15 hours a day,” he told Paul Desmond in a 1953 radio interview. “I did that over a period of three to four years.”

An early gaffe was immortalized in Clint Eastwood’s 1988 biopic, Bird. The 15-year-old Parker was at a jam session at Kansas City’s Reno Club, and somehow got two bars ahead of the form. As he soldiered on, oblivious, drummer Jo Jones used his ride cymbal to “gong” the hapless young saxophonist, but Parker paid no heed. Finally, Jones, in frustration, tossed the cymbal at the nervous young altoist’s feet. Mortified, Parker told his friends that he’d be back. But as Crouch put it, “Charlie Parker didn’t come back—not for a long time, not until he was sure he would never be so wrong again.”

Jack DeJohnette boasted a musical resume that was as long as it was fearsome.

Oct 28, 2025 10:47 AM

Jack DeJohnette, a bold and resourceful drummer and NEA Jazz Master who forged a unique vocabulary on the kit over his…

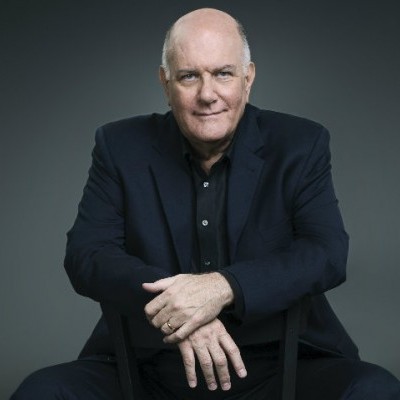

Always a sharp dresser, Farnsworth wears a pocket square given to him by trumpeter Art Farmer. “You need to look good if you want to hang around me,” Farmer told him.

Sep 23, 2025 11:12 AM

When he was 12 years old, the hard-swinging veteran drummer Joe Farnsworth had a fateful encounter with his idol Max…

D’Angelo achieved commercial and critical success experimenting with a fusion of jazz, funk, soul, R&B and hip-hop.

Oct 14, 2025 1:47 PM

D’Angelo, a Grammy-winning R&B and neo-soul singer, guitarist and pianist who exerted a profound influence on 21st…

Kandace Springs channeled Shirley Horn’s deliberate phrasing and sublime self-accompaniment during her set at this year’s Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival.

Sep 30, 2025 12:28 PM

Janis Burley, the Pittsburgh International Jazz Festival’s founder and artistic director, did not, as might be…

Jim McNeely’s singular body of work had a profound and lasting influence on many of today’s top jazz composers in the U.S. and in Europe.

Oct 7, 2025 3:40 PM

Pianist Jim McNeely, one of the most distinguished large ensemble jazz composers of his generation, died Sept. 26 at…